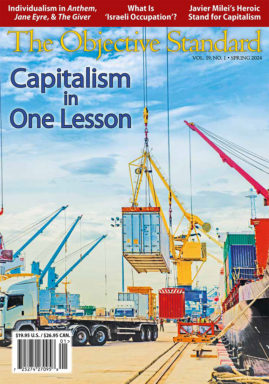

New York: Forge, 2019

711 pp. $9.99 (paperback)

Texas novelist Elmer Kelton’s West is a vivid, authentic world—one in which farmers struggle to keep their land, ranchers work backbreaking hours to support their families, cowboys explore the depths of the wilderness, and people make difficult but admirable choices in the face of adversity. To Kelton, who grew up on a ranch in Andrews County and was an associate editor of Livestock Weekly from 1968 to 1990, this life was all too familiar. In his spare time, he wrote novels based on his experiences, and by the time of his death in 2009, he had completed sixty-two books and was named the “greatest Western author of all time” by the Western Writers of America.1

Hot Iron, Kelton’s first novel (published in 1956), is an adventure story reminiscent of popular Westerns. The Time It Never Rained is a more serious Western and Kelton’s favorite, earning him a Spur Award for Best Western Novel in 1973.2 Together, these stories—reissued in 2019 in a single volume—demonstrate Kelton’s magnificent prose and are remarkable contributions to American literature.

Hot Iron

Espy Norwood, a troubled rancher, turns to alcohol as a means of muting his sorrow over the death of his wife. He embarrasses his young son, Kenny, with his drunkenness, motivating him to become sober and learn how to be a good father. Soon, he is offered a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to run a ranch on the Texas plains, where he brings Kenny to start a new life. But this transition is not easy, as Espy is greeted with hostility by resentful landowners, threatened by cattle thieves, and has difficulty repairing his relationship with Kenny. He chooses to deal with these situations with courage, honor, and determination.

For example, Mary Bowman, who was expecting to inherit the ranch from her father, is distraught when she learns of Espy’s arrival and soon antagonizes him. When a thug beats him up, takes his mules, and tries to intimidate him into leaving, Espy suspects Mary’s involvement. Instead of letting anger get the better of him, he sympathizes with her and tries to make amends:

Look, Miss Bowman, I don’t like us to be at odds with each other, and I don’t expect you do, either. I didn’t know I was shoving you out of a job you thought was yours and I’m sorry it happened that way. But there’s not much we can do about it now except take things the way they are and make the best of them.

We could get along fine, and I’d like to try. What say we just mark off our grievances and start fresh? (102)

Many of the ranch’s workers view Espy as an outsider and try to drive him out by refusing to do as he says. Once again, Espy remains firm, firing some of the unproductive workers. He does what he thinks is right and accepts responsibility for his actions, even when he risks being beaten up or robbed. Those who remain at the ranch admire Espy’s leadership and stand up for him.

Hot Iron is considered a “formula” Western because it follows a conventional plotline and has typical elements such as fistfights, shootouts between men on horseback, and cowboys discussing ranch life in bars. These aspects make for entertaining reading, but there is more to the book, including vulnerable moments that highlight the struggles of ranchers who worked during the early days of settlement in the Texas Panhandle.

Espy Norwood goes from being a misguided alcoholic to an honorable man who is capable of running a ranch, sticking to his beliefs, making peace with the locals, and raising his son. Because of this, Kenny learns to love his father and is motivated to become like him. Kenny soon stands up to the bully next door, learns to ride horses, and chooses to stay with Espy instead of returning to his aunt’s home. Finally, Mary Bowman recognizes that Espy’s presence doesn’t have to hinder her own success, and she learns to be a loyal business partner. With this touching story, Elmer Kelton shows that even those who make terrible mistakes are capable of redemption through conscious effort.

The Time It Never Rained

“Anything I’ve ever done on this ranch, I’ve done because I thought it was worth somethin’ to me,” declares Charlie Flagg, the protagonist of The Time It Never Rained. “If it’s worth buildin’, I’ll do it myself. If it’s not worth enough for me to spend my own money on it, it’s not right to expect somebody else to do it” (313). And Charlie means it.

Written in 1973, The Time It Never Rained dramatizes the lives of ranchers who struggled to survive during the real-life 1950s drought, when there was no significant rainfall for seven years. Before reliable transportation facilitated the shipping of feed for livestock, many animals simply starved to death. Many ranchers were financially ruined by the drought, sparking a federal aid program that aimed to sustain their farms. Kelton wrote that these programs were “inadequately planned and motivated more by political considerations than by sound appraisal of actual needs” (243–44). This, along with his fierce independence, is precisely why Charlie Flagg refuses to enroll in the government program. He accepts every hardship, even if it means losing his ranch.

Charlie lives with his wife, Mary; his son, Tom; and the Flores family on a ranch in Rio Seco. Initially, he doesn’t seem like much of a hero; he is older than Kelton’s typical protagonists, is distant toward his wife, expects his son to do as he is told, and is occasionally racist toward the neighboring Mexican immigrants. The other townspeople criticize him for his stubbornness, particularly his refusal to enroll in the government aid program, as everyone else has. With this, Kelton introduces the central conflict in the story: the decision to remain independent and accept nature’s course—or put oneself at the mercy of the government in order to get by.

The first half of the novel focuses on Charlie’s everyday struggles, which are difficult but manageable. Given that Charlie has enough help from the Flores family, Tom is able to leave the ranch to become a rodeo rider and send money back home. Eventually, as the drought persists, Charlie takes out loans from the bank to support his livestock and asks Tom to return. Little by little, he gives up parts of his ranch until he barely has anything left except a distant hope that one day it will rain again.

Charlie Flagg has flaws, but he nevertheless acts with conviction, honors his promises, and does the best he can to support his family. In him, Kelton created a monument to integrity. No matter how many of his fellow ranchers and friends try to convince him to betray his standards, Charlie refuses. For example, Charlie’s old friend Page Mauldin says,

That’s the difference between us, Charlie. You don’t believe in this stuff and you stand by your convictions. I don’t believe in it either, but I take it because it’s easy money and because everybody else does. You’ll shove your feet under a poor man’s table as long as you live. (315)

Charlie does not morally condemn Page or any others who accept financial help; instead, he holds that “what anybody else wants to do is his business, not mine. I just want to live by my own lights and be left the hell alone” (508).

As time goes on, other characters in the novel learn valuable lessons of individualism from Charlie, enabling them to succeed in their own endeavors. For example, when young Manuel Flores’s pony dies, he tells Charlie that he will become a vet one day so he can return to Rio Seco and save animals. In the 1950s, few Mexican Americans were afforded such educational opportunities. Whether Manuel achieves this dream is left open, but his character develops strongly in this direction. Page’s daughter, Kathy, is most like Charlie in that she does not give in to female stereotypes and is determined to run her father’s ranch as she sees fit.

These characters come together in a beautifully crafted story, evocative of the Texas spirit Kelton admired in his father and other ranchers of his time. As Tom Pilkington writes in the afterword of the novel, Charlie Flagg

embodies what we believe were the best qualities of the legendary Texan rancher: strength of will, independence, self-sufficiency. He loves and respects the land, harsh and unyielding as it is. His sense of right does not waver. He opposes equally the inert, clotted force of bureaucratic regulation and the evil of untrammeled power that too often crushes the powerless. (708)

Hot Iron and The Time It Never Rained are not only unforgettable Western novels, but literature well worth the time for anyone seeking heartwarming and inspiring stories.

Click To Tweet

You might also like

1. Macy Halford, “Elmer Kelton,” New Yorker, August 23, 2009, https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/elmer-kelton; R. G. Robertson, “The Greatest Western Author of All Time,” True West Magazine, October 1, 2002, https://truewestmagazine.com/the-greatest-western-author-of-all-time/.

2. “Awards,” Elmer Kelton, https://www.elmerkelton.net/awards (accessed July 9, 2021).