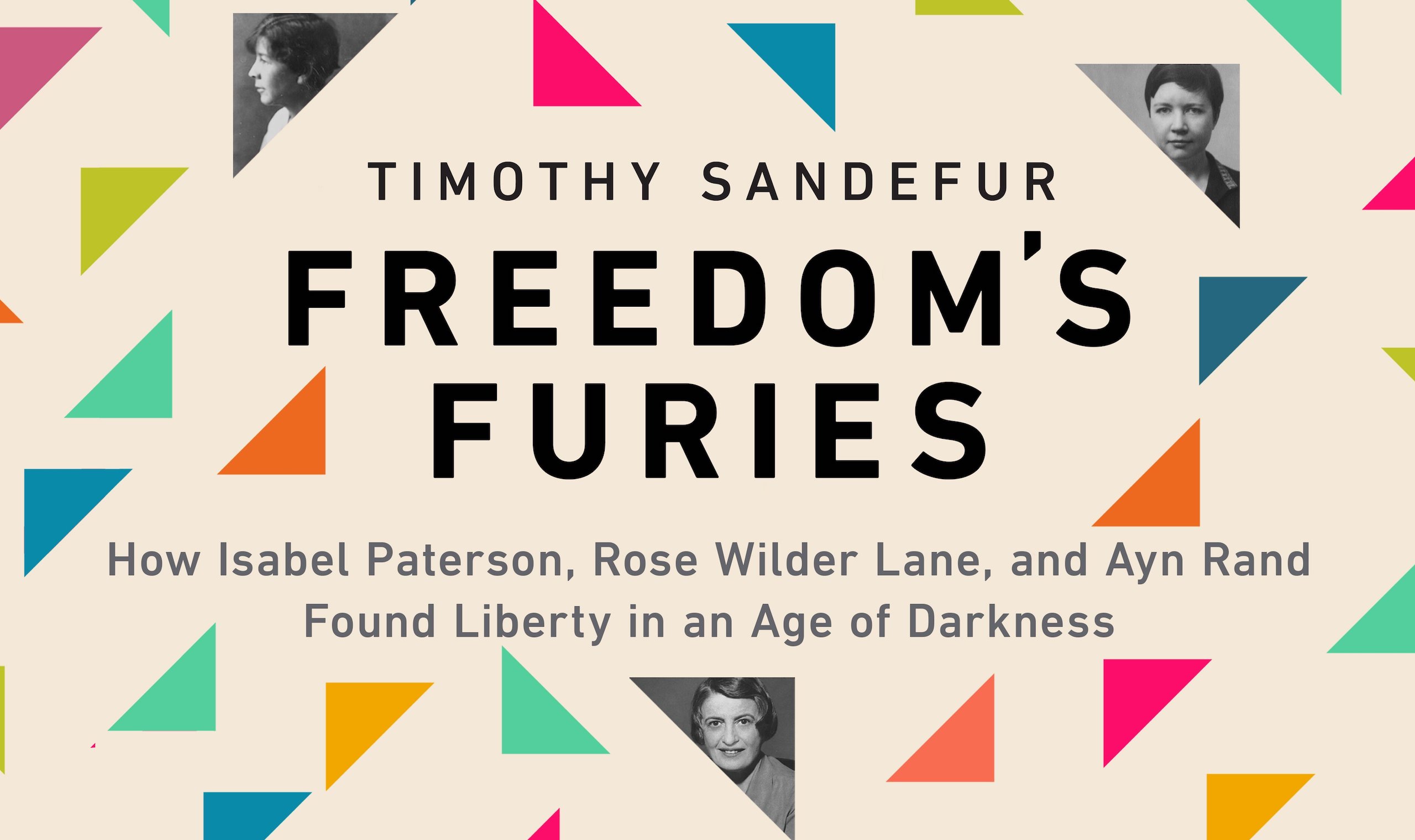

Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute, 2022

404 pp. $19.95 (paperback)

In 1943, the world was at war, and the barbaric regimes of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan occupied much of Europe and Asia. America, the “sleeping giant,” had awakened to thrust its industrial might against those regimes. Yet, on American soil, leading thinkers had embraced versions of the authoritarian ideologies of Europe and attacked the nation’s classical liberal foundations. They proclaimed a new era in which top-down control by a political elite would replace individualism. As Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared, “the day in which individualism was made the great watchword of American life” had ceased (118).

Yet in that same year, three books pushed back against the authoritarian tide and forever changed the course of American political thought. Two of the books examined the importance of individual liberty to human flourishing: Isabel Paterson’s The God of the Machine and Rose Wilder Lane’s The Discovery of Freedom. The third was a “hymn to individualism” more broadly and became a blockbuster: Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead (306).

How these three authors radically opposed prevailing trends, became friends, and gave birth to the modern American liberty movement is the topic of Timothy Sandefur’s Freedom’s Furies: How Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane, and Ayn Rand Found Liberty in an Age of Darkness.

Freedom’s Furies is primarily an intellectual and artistic biography of its three subjects, including summaries of many of their works with elucidating commentary. . . .

Click To Tweet