My motive and object in all my political works . . . have been to rescue man from tyranny and false systems and false principles of government, and enable him to be free, and establish government for himself. —Thomas Paine1

Benjamin Franklin told Thomas Paine that he was “more responsible than any other living person on this continent for the creation of . . . the United States of America.”2 And Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense—published in January 1776, a mere six months before the Declaration of Independence—is recognized as the publication that turned the tide of opinion in favor of American independence.

But Paine’s impact on history continued far beyond 1776. As the War of Independence took its toll on America, Paine kept the spirit of the revolution alive with his American Crisis essay series. After the war, not content with helping to create one new country, he returned to Europe to help establish a new republican France during the French Revolution. During that time, Paine further developed his ideas, writing the two works that most fully embody his philosophy: Rights of Man and The Age of Reason. In these works, he bravely took on both the most powerful institutions in the Western world—the European aristocracy and the church—at a time when such opposition brought the risk of banishment, imprisonment, even execution. Such consequences could be the price of integrity for an independent thinker such as Paine, as he would learn.

The story of how Paine went from being the struggling son of a farmer and dressmaker in rural England to becoming one of the most influential figures in world history is one of determination, tragedy, and perseverance. The thirty-eight years of Paine’s life before his arrival in America in 1774 were beset with crisis after crisis—experiences that would have defeated most men but gave Paine the experience and fortitude he would need to become the historic giant we now remember.

Early Writings and a Fortuitous Encounter

Paine’s life before and after his move to America could be the lives of two different people. Born Thomas Pain in 1737 in the remote English town of Thetford, he had little schooling and worked as an apprentice in his father’s stay-making (dress-making) business.3 However, after a failed attempt at running his own stay-making business and brief spells as a privateer and a schoolteacher, he moved to the more affluent south coast town of Lewes and became an excise officer (essentially, a tax collector). Despite the apparent contradiction between this role and his later hostility to most taxation and to the British government, this experience laid crucial groundwork for his future career as a writer.

While in Lewes, he became increasingly active in local politics, developing his oratory skill in the town’s public houses and meeting halls. It was during this time that Paine developed his strong belief in individual liberty and his antagonism toward Britain’s established monarchical and aristocratic systems, but little detail of this period of his life survives. According to University of Sussex researcher Paul Myles, who established the Thomas Paine Project to study Paine’s early development, “The mystery is how Paine came to have these ideas that led to him writing Common Sense, the book that convinced American colonists that they should fight for independence.”4

Paine’s reasoning and argumentative skills are evident in his 1772 work, The Case of the Officers of Excise, a plea for better pay and working conditions for excise officers, and his first published work on politics. Although its style is less refined than Paine’s later works, it indicates his eloquence and persuasiveness:

The trust unavoidably reposed in an Excise Officer is so great that it would be an act of wisdom, and perhaps of interest, to secure him from the temptations of downright Poverty. To relieve their wants would be charity, but to secure the revenue by so doing would be prudence.5

This work earned him a good reputation among the excise officers, which, despite his dismissal from the Office of Excise in early 1774, led him to an encounter that would change his life forever. While Paine was in London trying to build his reputation as a writer and orator, his friend, Commissioner of the Excise George Lewis Scott, who also happened to be a Fellow of the Royal Society, introduced him to a visiting American statesman, one Benjamin Franklin.6

Franklin, who was preparing to leave Britain, having become convinced that no amount of diplomacy would persuade the British government to alter its policies toward the American colonies, was impressed by Paine and “procured his passage” to America.7 Paine, at this point deep in debt after a string of business failures and dismissals, readily accepted. It is not known what exactly about Paine motivated Franklin to extend this offer, but in a letter to his son-in-law he described Paine as “well recommended to me as an ingenious worthy young man.” He wrote several such complimentary letters introducing Paine to various people of note in Philadelphia.8

Arriving in Philadelphia in November 1774 after a perilous sea voyage (including a typhoid fever infection that nearly killed him), Paine spent several months recovering before leveraging Franklin’s letters to secure a position as editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine, Philadelphia’s first illustrated journal, which publisher Robert Aitken was about to launch.

‘The Times That Try Men’s Souls’

Aitken and Paine intended the Pennsylvania Magazine (subtitled The American Monthly Museum) to be a general interest publication with subjects ranging from mathematics to pest control. However, the question of America’s relationship with Britain ultimately defined the magazine’s short eighteen-month run. Paine wrote in the January 1775 inaugural issue:

We presume it unnecessary to inform our friends that we encounter all the inconveniences which a magazine can possibly start with. . . . the principal difficulty in our way is the present importunate situation in public affairs . . . every heart and hand seems to be engaged in the interesting struggle for American liberty.9

The magazine’s crest featured the Goddess of Liberty together with cannonballs, battle-axes, and pikes, even though open war had not yet begun.

A few months later, however, the long-standing tensions over Britain’s mistreatment of the colonies, exacerbated by the “Intolerable Acts” of 1774, erupted into violence with the battles of Lexington and Concord. The Philadelphia Magazine began regular reporting on the fighting as well as special segments intended for soldiers. But these skirmishes did not yet constitute a war of independence. Many Americans, including many of those taking up arms, still thought reconciliation with Britain was the way forward. In Paine’s words (writing in 1778), the colonists’ “attachment to Britain was obstinate, and it was, at that time, a kind of treason to speak against it. Their ideas of grievance operated without resentment, and their single object was reconciliation.”10

Paine sought to change that. He began writing a series of articles that would, for the first time in print, unreservedly advocate for a fully independent American nation. As he worked, Paine realized that the pieces would function better if published as a single work, and so Common Sense (originally titled Plain Truth) was born.11

Published on January 10, 1776, Common Sense, in the words of Benjamin Rush, “burst from the press with an effect which has rarely been produced by types and paper in any age or country.”12 It sold 120,000 copies in three months, rising to 500,000 by the end of the Revolutionary War—when the total population of the thirteen colonies was only 2.5 million.13 Addressing those who couldn’t conceive of an America divorced from the “mother country,” Paine wrote, “A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason.”14

But it was Paine’s reasoning that made converts, and in short order. Thanks to the pamphlet’s wide-reaching impact, public opinion rapidly turned in favor of independence. In the words of John Adams, “Common Sense, like a ray of revelation, [came] in seasonably to clear our doubts, and to fix our choice.”15 Part of why it was so effective was Paine’s decision to use plain, common language, rather than the complex “academese” of other political and philosophical writers, such as Joseph Priestley who, Paine biographer Craig Nelson notes, included a 222-word sentence in his 1768 Essay on the First Principles of Government.16

Paine, on the other hand, “knew people weren’t thinking in the abstract,” biographer Harvey J. Kaye explains. “Paine wrote to his peers, in a language everyone could understand.”17 This also made the work easy to read aloud for the illiterate, further boosting its reach. Even Paine’s critics acknowledged his success in designing Common Sense to reach and move the masses. His fierce critic Friedrich Von Gentz, for instance, complained that it “was solely calculated to make an impression on the mass of the people.”18

In Common Sense, Paine laid out his vision for a truly free nation, one in which all people are equal before the law: “As in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.”19 America, Paine thought, was ready to throw off the legacy of kings and become the first such free country on Earth. He also espoused the principle of separation of church and state, which would go on to be a pioneering feature of American government, remarking, “As to religion, I hold it to be the indispensable duty of all government, to protect all conscientious professors thereof, and I know of no other business which government hath to do therewith.”20

The vision of a free nation Paine painted in Common Sense differs in some respects from the America the Founders would ultimately create. For example, Paine called for a unicameral legislature—a single democratically elected house combining all the functions of government—arguing that this provided a simpler, more transparent system that would inhibit a government’s attempts to enslave its citizens.21 Later in 1776, John Adams remarked in his Thoughts on Government that such a legislature could leave a state at the mercy of a tyrant who could seize control of the whole system in one go. Adams proposed limiting this risk with the three-branch structure and bicameral legislature that would later be established in the United States Constitution.22 (Paine would later come around to a similar view after seeing the unicameral Pennsylvania legislature in action and recognizing that it left the government exposed to easy takeover by a particular political faction.)

Despite the Declaration of Independence rallying the colonists’ spirits, many thought the colonial militias stood little chance against the world’s most powerful army and the vicious Hessian mercenaries that accompanied the British forces, and a series of early defeats compounded that skepticism. Keen to play an active part in the war, Paine joined George Washington’s forces, assisting them with mechanical and mathematical tasks during the day and writing reports of their progress (or lack thereof) by campfire at night.23 But Paine was quickly “wearied almost to death with the retrograde motion of things,” and it became clear to Washington and others that Paine’s usefulness to the war lay in the motivational impact of his writing. Drawing on his experiences on the front lines, Paine began publishing a series of pamphlets to motivate the troops, titled American Crisis. The first of these, read to Washington’s troops before they began their legendary crossing of the Delaware, began with the immortal lines:

These are the times that try men’s souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: It is dearness only that gives every thing its value.24

Paine remained a member of the military for seven years while publishing the Crisis series, which ultimately included sixteen pamphlets released between 1776 and 1783. He also took an active role in local government in his home state, helping shape the 1776 Pennsylvania State Constitution.

However, Paine’s reputation in America took the first of several hits due to the 1778–79 Silas Deane Affair, during which he exposed diplomatically sensitive information while commenting on public accusations that Deane, an American diplomat, had abused his position to make his own arms deals while on a diplomatic mission in France.25 This led the Secret and Commercial Committee of the Continental Congress to dismiss Paine from his seat on the committee. His subsequent essay, “Public Good,” also upset many of his friends by proposing that the former British land west of the thirteen colonies properly belongs to Congress and not to individual speculators.

But Paine continued his work to support American independence and the establishment of a rights-protecting government. After a visit to Europe to seek French financial support for the Revolutionary War, he remained active in the debates on the U.S. and various state constitutions, as well as in French-American relations. During this time, he also published his often-overlooked Dissertations on Government, an intellectual bridge between Common Sense and his later works, in which he laid out more complete proposals for his preferred republican system.26 Observing that a monopoly on coercive power is the essential feature of a government, he explained:

It is impossible to construct a form of government in which this power does not exist, so there must of necessity be a place, if it may be so called, for it to exist in. . . . In despotic monarchies this power is lodged in a single person, or sovereign. His will is law; which he declares, alters, or revokes as he pleases, without being accountable to any power for so doing. Therefore, the only modes of redress, in countries so governed, are by petition or insurrection. . . . In Republics, such as those established in America, the sovereign power, or the power over which there is no controul and which controuls all others, remains where nature placed it; in the people; for the people in America are the fountain of power. It remains there as a matter of right, recognized in the constitutions of the country, and the exercise of it is constitutional and legal. . . . Therefore the republican form and principle leaves no room for insurrection, because it provides and establishes a rightful means in its stead.

In the Dissertations, Paine went on to outline in detail the democratic process for enabling the people to choose and remove leaders in this system. However, he would not fully expound the underlying philosophical justification for such a system—the principle of man’s rights—until his next major work on politics.

Rights of Man

Paine had long taken interest in the deeper principles underlying politics, and he strongly believed that all men should have equal representation in government, regardless of wealth or property. Sometimes called “the first American abolitionist,” Paine had published the article “African Slavery in America” in 1775 (right as the American Revolution was reaching its tipping point), after which he helped draft and subsequently signed the Act of Pennsylvania abolishing slavery in 1780, dubbed the first such act in Christendom.27

So, he was greatly excited when, in 1789, a popular uprising in France deposed that country’s monarchy in the name of liberty and equality—the first of what Paine believed would be a wave of such revolutions that would rid Europe of monarchy for good. Paine had already used more letters of introduction from Franklin to befriend major French reformists—the Marquis de Lafayette in particular—and his interactions with them strengthened his belief that the revolution was in good hands and would proceed along lines similar to that in America.

Having returned once again to Europe, Paine began work on Rights of Man, a publication that would defend the principles of the French Revolution from its critics in Britain and America. Unlike Common Sense, Rights of Man explored deeper philosophic questions, primarily setting out to answer the most fundamental question regarding the rights of man: “what are those rights and how came man by them?”28

Paine opened Rights of Man with a warm dedication addressed to Washington, indicating his belief that the French Revolution signaled a European adoption of American principles:

Sir, I present you a small treatise in defence of those principles of freedom which your exemplary virtue hath so eminently contributed to establish. That the Rights of Man may become as universal as your benevolence can wish, and that you may enjoy the happiness of seeing the New World regenerate the Old, is the prayer of . . . Your much obliged, and obedient humble servant, Thomas Paine.29

A major factor in Paine’s decision to produce Rights of Man was the 1790 publication of Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, which branded the revolution a “disaster,” arguing that those storming the Bastille “destroyed all the balances and counterpoises which serve to fix the state and to give it a steady direction, and which furnish sure correctives to any violent spirit which may prevail in any of the orders.”30 Although Burke had supported American independence, he advocated the system of constitutional monarchy established in Britain following the 1688 “Glorious Revolution,” which, in his view, secured rights to justice and property. By contrast, he thought the French Declaration of the Rights of Man “subverted the state, and brought on such calamities as no country, without a long war, has ever been known to suffer, and which may in the end produce such a war, and perhaps many such.”31 (This particular prediction of Burke was subsequently proven correct by the Reign of Terror and the rise of Napoleon.)

Much of part I of Rights of Man (published in 1791) consists of specific repudiations of points in Burke’s essay, but toward the end, Paine tackles the more fundamental question of the nature of rights and the proper role of government. Unlike Burke’s pamphlet, which argued that rights are a product of tradition, “an entailed inheritance derived to us from our forefathers, and to be transmitted to our posterity,” Rights of Man argued that rights come from nature and cannot be granted by government.32 Rather, Paine articulated, the government’s job is to protect rights:

It is a perversion of terms to say that a charter gives rights. It operates by a contrary effect—that of taking rights away. Rights are inherently in all the inhabitants; but charters, by annulling those rights, in the majority, leave the right, by exclusion, in the hands of a few.33

As was common at the time, Paine’s held that man has “natural rights,” and these “appertain to man in right of his existence. Of this kind are all the intellectual rights, or rights of the mind, and also all those rights of acting as an individual for his own comfort and happiness, which are not injurious to the natural rights of others.” As these rights belong to every man by nature (Paine, in the spirit of John Locke, described them as “a property of the most sacred kind”), they precede government—they do not come from it. “Man did not enter into society to become worse than he was before, nor to have fewer rights than he had before, but to have those rights better secured.”34

Paine also held: “We must not confuse the peoples with their governments.”35 When he wrote, for instance, “That which a whole nation chooses to do it has a right to do,” he used “nation” to refer to the people of the country, not its government.36 Unfortunately, by ascribing rights to a group in this way, Paine engaged in a contradiction and left the door open for majorities to vote away the rights of minorities. Recognizing this risk, many of the other Founders opposed direct democracy. This is a notable weakness in Paine’s political philosophy. He did, however, hold that governments don’t have rights, saying that governments are “only the organ of the Nation, and cannot possess inherent rights.”37

In the second part of Rights of Man (1792), Paine made further distinctions between government and people, noting that individuals, not governments, create the values on which human life depends—but governments typically take the credit for them:

Though [government] avoids taking to its account the errors it commits, and the mischiefs it occasions, it fails not to arrogate to itself whatever has the appearance of prosperity. It robs industry of its honours, by pedantically making itself the cause of its effects; and purloins from the general character of man, the merits that appertain to him as a social being.38

Governments not only take credit for people’s productive activity, Paine observed; they also take credit for basic decency among men: “Great part of that order which reigns among mankind is not the effect of government. It has its origin in the principles of society and the natural constitution of man. . . . Society performs for itself almost everything which is ascribed to government.”39

These comments may seem at odds with later passages in part II, in which Paine advocated replacing Britain’s tax-funded monarchy with a kind of welfare state. At the time, the British government levied wide-ranging heavy taxes that Paine (a fan of the economics of Adam Smith) identified as destroying human potential and misusing government power. One such tax was the window tax, which taxed property owners based on the number of windows in their homes, leading many to brick up their windows to reduce their tax burden (17th- and 18th-century buildings with bricked up windows can still be found across Britain today). Another was the “poor rates,” a tax that the parish’s community leaders (usually hereditary nobility) used to “help the poor” according to their own ideas about who qualified and what type and amount of assistance they should receive.

Paine’s solution was to replace these taxes and several others with a much smaller tax (saving money no longer spent on monarchy and wars) levied on the inheritance of land, which, unlike the poor rates, government would pay directly to the poor, elderly, and ex-military. As noted earlier, Paine held that the sole function of government is to protect rights, but he believed that it was impossible to exercise one’s rights in a state of abject poverty. And he seems to have embraced the contradictory position that people have a right to government financial support to ensure that all have enough to survive. (As Ayn Rand would later observe, taxing people to help others violates rights: “Since man has to sustain his life by his own effort, the man who has no right to the product of his effort has no means to sustain his life. The man who produces while others dispose of his product, is a slave.”)40

But Paine’s error here is understandable. In his time, the landed aristocracy abused the poor who worked their lands—manor estates that had been granted by the crown centuries earlier. This was the injustice he sought to correct. These land grants, dating back to the feudal system, originally came with an obligation to allow peasants and tenants to work the land, but changes in the law allowed lords to “enclose” their manors, often evicting people in the process (sometimes depopulating entire villages) or keeping them from passing that land to their descendants. As a result, many poor people were dispossessed, and much of the land was enclosed in private manors belonging to the nobility. Poverty-stricken tenants or evictees who tried to use the lands they previously were entitled to, or who engaged in petty theft to survive, were met with severe—often capital—punishment.41 Thus, as Paine observed, “When in countries that are called civilized, we see age going to the workhouse and youth to the gallows, something must be wrong with the system of government.”42

Paine was correct in this observation; this manorial system and the subsequent enclosures transferred the productive effort of tenant farmers to the descendants of knights and barons, enabling them to effectively become wealthy off the backs of those who had worked the lands those descendants had inherited. By proposing a tax on the nobility’s land inheritance to fund payments to the poor, Paine hoped to correct this, providing support to poor people “as a compensation in part, for the loss of his or her natural inheritance, by the introduction of the system of landed property” (i.e., the system of nobles holding lands granted by the crown, in which “The Aristocracy . . . are the mere consumers of the rent”).43

Some cite Paine as an early proponent of the kinds of welfare programs we see in modern societies, but in so doing, they often take him out of context. On Paine’s view, for it to be right to “distribute [private property] equally it would be necessary that all should have contributed in the same proportion, which can never be the case.”44 Paine did advocate an early form of welfare, but not one funded by taxing a person’s income from his work, nor one in which bureaucrats decide how the collected funds are to be used. Paine’s goal was to free people by undoing the legacy of English feudalism, not to punish productivity. When the U.S. Social Security Administration, for example, claims that its gigantic system of handouts to one-fifth of America’s population, funded by general taxation on income and business activity, is “a program like Thomas Paine suggested,” it ignores these crucial differences.45

Paine was thoughtfully convinced that his principles were right and that common sense demanded their immediate adoption across the civilized world. In the words of priest-turned-philosopher and Paine devotee Elihu Palmer, “The writings of Paine bear the most striking relation to the immediate improvement and moral felicity of the intelligent world. He writes upon principle, and he always understands the principle on which he writes.”46 Unfortunately for Paine, his principled outspokenness landed him in serious jeopardy twice in quick succession.

His troubles began in England, where he was branded a traitor and had to flee to France. Shortly after his escape, he was tried in absentia on a charge of “seditious libel” for the antimonarchist content in part II of Rights of Man. The prosecution argued that Paine,

being a person of a wicked, malicious, and seditious disposition; and wishing to introduce disorder and confusion, and to cause it to be believed, that the Crown of this kingdom was contrary to the Rights of the Inhabitants of this kingdom . . . did . . . wickedly, falsely, maliciously, scandalously, and seditiously publish a certain book, called the Second Part of Rights of Man . . . containing many false, wicked, scandalous, malicious, and seditious assertions.47

Tellingly, the government had not taken issue with Rights of Man when it was priced at three shillings—unaffordable to most lay readers—but only when Paine released a cheaper edition in lower-quality binding.48

In his “Letter Addressed to the Addressors on the Late Proclamation” (in response to George III’s 1792 royal proclamation against Rights of Man), Paine highlighted the importance of standing on principle in the face of opposition, writing, “Moderation in temper, is always a virtue; but moderation in principle, is a species of vice.” Both agencies that published the letter in London were subsequently prosecuted.49 Paine was found guilty of the sedition libel charge and never returned to England.

Paine’s circumstances then appeared to improve. Following the publication of part II of Rights of Man, while Paine was still living in France, he was invited to become a member of the French National Convention and an honorary French citizen. This required him to speak through an interpreter, as he was unable to speak French himself. Nonetheless, he vigorously took part in planning and establishing the new French government, regarding it as the blueprint for a future republican Europe. Indeed, Paine’s early enthusiasm for the French Revolution sometimes ran away with him; he was so enamored with it that he even began planning a French invasion of England to depose King George.

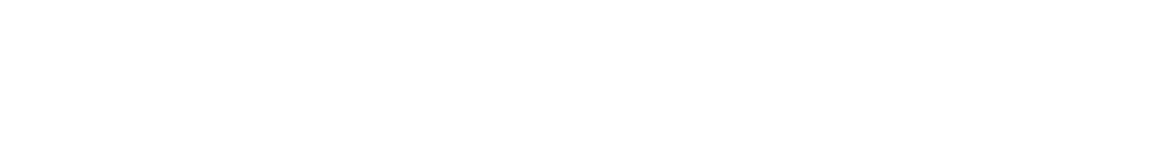

But his troubles had only just begun. The following year, as the violent proto-socialist Jacobin movement increasingly took control in France, Paine’s nonviolent views (especially his outspoken opposition to executing the deposed King Louis XVI and to the death penalty in general) made him an enemy in the eyes of Robespierre’s mob. Branded a friend of the Ancien Regime, he was thrown into a Paris jail for a year and only dodged the guillotine thanks to a jail functionary hanging the sign for his execution order on the wrong side of his cell door.50 Shortly thereafter, the newly appointed American ambassador to France, James Monroe, helped secure Paine’s release, and he was reinstated to the National Convention. Paine publicly held Monroe’s predecessor, Gouverneur Morris, and then-President Washington responsible for failing to come to his rescue, accusing Washington of weakness. This cost him many friends in America in his later years.

Paine remained active in France for most of the 1790s but could no longer support the revolution. Nor could he support the turn France had taken regarding religion, which would be the focus of his next major work.

The Age of Reason

Taken aback by the Jacobin government’s prohibition of religion in France, Paine decided to write a work on religion to ensure that “in the general wreck of superstition, of false systems of government and false theology, we [do not] lose sight of morality, of humanity and of the theology that is true.”51 Raised a Quaker, Paine took religion seriously throughout his life—indeed, he relied on religious and Biblical arguments in many of his earlier works.52 Even as late as Rights of Man, Paine remarked that “all religions are in their nature kind and benign.”53

Despite this, Paine, in his characteristically confrontational manner, produced a work that relentlessly attacked organized religion—Christianity in particular, which, by this time, he considered to be “false theology.” Although he believed in a god, Paine remarked, “I do not believe in the creed professed . . . by any church that I know of. My mind is my own church.”54 He passionately believed in the power of an individual’s reasoning mind to understand reality and thereby to dismiss religious doctrine when it conflicts with evidence and reason. He opened The Age of Reason by saying, “The most formidable weapon against errors of any kind is reason. I have never used any other, and I trust I never shall.”55

Paine observed that the articles of Christian faith almost always stand at odds with reason and science. “Such is the strange construction of the Christian faith,” he reflected, “that every evidence the heavens afford to man, either directly contradicts it, or renders it absurd.”56 In his view, moral ideas, too, must accord with experience and common sense. “Morality is injured by prescribing to it duties, that, in the first place, are impossible to be performed, and if they could be would be productive of evil.”57 Similarly, the Christian notion of original sin—the idea that all people are born guilty of “wrongs” committed by others against God in the past—contradicts Paine’s idea of morality: “Moral justice cannot take the innocent for the guilty, even if the innocent would offer itself. To suppose justice to do this, is to destroy the principle of its existence, which is the thing itself. It is then no longer justice. It is indiscriminate revenge.”58 He took a similar view of Christ’s instruction to “love thy enemy,” saying, “Loving of enemies is . . . a dogma of feigned morality, and has besides no meaning. . . . To love in proportion to the injury, if it could be done, would be to offer a premium on the crime.”59

Paine was a deist, meaning he believed in a god that created the universe but takes no active role in it. A key aspect of Paine’s deism is his belief that, “The creation is the Bible of the deist”—meaning that one’s means of knowing God is not a book but nature itself. Paine thought that any “written or printed books . . . are the works of man’s hands, and carry no evidence in themselves that God is the Author of any of them.”60 Rather, in his view, the only way to truly hear the word of God is to scientifically study the natural world. “Natural philosophy [is] the true theology,” he wrote.61 Paine took the existence of a deistic god as self-evident given the construction of the natural world (an understandable view given the extent of scientific knowledge at the time), and he saw no conflict between belief in such a being and an intransigent commitment to the rational study of nature—indeed, he held, true belief in God required it.

Although The Age of Reason is essentially a work of deistic philosophy, it also has a political dimension. Paine regarded organized religion and monarchy as two facets of the same problem: people seeking power over others. “All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish [Muslim], appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit,” he wrote.62 Reason, he held, is man’s means of knowing reality, and knowledge of reality is knowledge of God. Accordingly, the evidence for God is available to any reasoning mind: “A thing which everybody is required to believe, requires that the proof and evidence of it should be equal to all.”63

True understanding, in Paine’s view, could only come from one’s own use of his rational faculty, not from others:

As to the learning that any person gains from school education, it serves only, like a small capital, to put him in a way of beginning learning for himself afterward. Every person of learning is finally his own teacher; the reason of which is, that principles, being of a distinct quality to circumstances, cannot be impressed upon the memory. Their place of mental residence is the understanding, and they are never so lasting as when they begin by conception.”64

Correspondingly, a society in which people are free to think and learn for themselves is essential to the discovery of truth. “When opinions are free, either in matters of government or religion, truth will finally and powerfully prevail.”65

Paine’s devotion to these ideas was not only theoretical; he was also active in practical science and held himself to the same high standard of attention to detail and extensive provision of evidence in his scientific work. He wrote a paper on the means of generating motion, proposed designs for innovative single-arch iron bridges (at least three of which were built) and vaulted roofs, and even speculated on the causes of yellow fever. In all these writings his dedication to reason shines through, just as in The Age of Reason and his earlier political works.

Knowing he had little time to complete a draft before his impending imprisonment in Paris, Paine wrote part I of The Age of Reason in a hurry, completing the draft just in time to send it to a publisher before his arrest. As with Common Sense, he wrote The Age of Reason in layman’s language, making common deistic arguments against organized religion accessible to a much larger audience. As a result, the book sold well in America and led to a surge in deism there.

Knowing that he might be arrested at any moment, Paine worked to complete part I with no Bible at hand. As such, he relied on his memory of the testaments and so chose to largely attack them on broad principle rather than specific inconsistencies. (Even so, he impressively relayed numerous direct quotes from memory.) In part II, he once again had access to a Bible, enabling him to quote more extensively and correct his quotations where critics had pointed out errors. In so doing, he noted that the biblical texts were “much worse . . . than I had conceived” and that he had treated them “better . . . than they have deserved.”66

Paine remained in France until the turn of the century, founding the Society of Theophilanthropists (meaning “Friends of God and Man”) in Paris in 1797.67 It argued for the existence of God and against organized religion (it was later shut down by Napoleon).

Upon returning to America in the early 1800s, Paine began work on a part III of The Age of Reason, subtitled An Examination of the Passages in the New Testament, Quoted from the Old and Called Prophecies Concerning Jesus Christ. This brought him into conflict with his old friend and then-U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, who opposed the pamphlet’s release out of fear of a public backlash.68 Paine ultimately released part III several years later in 1807, close to the end of his life, despite Jefferson’s protestations.

Survival and Decline

Given Paine’s massive positive impact on world history, it’s sobering to contemplate the numerous times he came within a hair’s breadth of dying.

The first was when, at the age of sixteen, he fled his hometown and enlisted to serve as a privateer on the Terrible under the command of Captain William Death.69 (These are the real and well-deserved names of both ship and captain.) Death, his brother, and most of the crew were killed on the ship’s next voyage, which Paine only escaped thanks to a timely intervention by his father just before its departure.

Having survived long enough to meet Franklin and leave for America, Paine then very nearly died from the typhoid fever that he suffered during the voyage. The conditions on such multi-week transatlantic journeys were unsanitary, which, combined with the turbulent conditions and limited supplies on board, meant that fatal illnesses were common. Paine had to be nursed back to health gradually over five months following his arrival.

Paine’s third close brush with death came when he was scheduled for beheading during his imprisonment on the orders of Robespierre. The blind luck of a wrongly hung sign saved his life.

Despite his several brushes with death, Paine’s actual end was sadly anticlimactic and lonely. Compounding the friends and supporters he had lost by attacking Washington, his opposition to Christianity in The Age of Reason cost him much of his remaining support in America and burned many of his surviving relationships, including with Benjamin Rush. “His principles,” wrote Rush to the English political writer James Cheetham, “avowed in his ‘Age of Reason,’ were so offensive to me that I did not wish to renew my intercourse with him.”70 Even Jefferson, who shared many of Paine’s views on religion and whom Paine had publicly supported as a presidential candidate, distanced himself from Paine during his time in office.

Paine’s final years until his death in 1809 were increasingly lonely. He ended his life poor and out of fashion in an America that was increasingly turning back to religion during the “Second Great Awakening.” This more religious America did not look fondly on Paine. He was substantially forgotten and occasionally condemned. As late as 1888, Theodore Roosevelt described him as “a filthy little Atheist.” In 1893, however, with the publication of Moncure Daniel Conway’s The Life of Thomas Paine and his republication of Paine’s corpus, interest in his work was revived.

In June 1809, Thomas Paine, an architect of the American Revolution, was buried under a tree on his farm with just a few mourners in attendance. Robert Ingersoll later reflected on this underwhelming send-off:

One by one most of his old friends and acquaintances had deserted him. Maligned on every side, execrated, shunned and abhorred—his virtues denounced as vices—his services forgotten—his character blackened, he preserved the poise and balance of his soul. He was a victim of the people, but his convictions remained unshaken. He was still a soldier in the army of freedom, and still tried to enlighten and civilize those who were impatiently waiting for his death.71

Thomas Paine went from obscurity to stardom as one of America’s most celebrated writers, only to end his life back in obscurity. Today, he is once again widely celebrated for spearheading the cause of American independence with Common Sense, but that barely scratches the surface of his contribution. Paine defended rights and reason in words that everyone could understand, enlightening the masses and transforming societies on both sides of the Atlantic.

Click To Tweet

You might also like

1. Thomas Paine, “Letter to John Inskeep,” February 10, 1806.

2. Joseph M. Hentz, The Real Thomas Paine (Bloomington, IN: iUniverse Books, 2010), 218.

3. Thomas Paine author profile, Penguin Random House, https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/authors/23075/thomas-paine. Authors disagree on when Paine added the “e” to his name. Biographer Craig Nelson follows earlier biographers in holding that it followed Paine’s arrival in America and refers to him as “Pain” when discussing his Pennsylvania Magazine work, but the British National Archives for church services show him using “Paine” in 1768. It’s possible that he used both versions concurrently for a period.

4. Jacqui Bealing, “New Project Aims to Uncover Thomas Paine’s Revolutionary Influences” (Brighton: University of Sussex, July 10, 2012), https://www.sussex.ac.uk/broadcast/read/14478.

5. Thomas Paine, “The Case of the Officers of Excise,” 1772.

6. Samuel Willard Crompton, Thomas Paine: Political Activist and Author (New York: Chelsea House, 2013).

7. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/benjamin-franklin-joins-the-revolution-87199988/.

8. Craig Nelson, “Thomas Paine and the Making of Common Sense,” New England Review 27, no. 3 (2006): 228.

9. Albert H. Smyth, The Philadelphia Magazines and Their Contributors, 1741–1850 (Philadelphia: Robert M. Linsday, 1892), 48–49.

10. Thomas Paine, “The Crisis, No. VII: To the People of England,” 1778.

11. Some earlier works had proposed varying degrees of legislative independence. One such is Thomas Jefferson’s “A Summary View of the Rights of British America” (1774), which although promoting local governance, still expresses the hope that such arrangements “can continue both to Great Britain and America the reciprocal advantages of their connection.” There is debate to what extent Benjamin Rush influenced the form and content of Common Sense. Rush attested to having overseen every chapter and recommending the name Common Sense, but Nelson disputes this account as incongruent with the pamphlet’s content and Paine’s own recollections of discussing it with Franklin.

12. Moncure Daniel Conway, ed., The Life of Thomas Paine, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1892).

13. “Thomas Paine: The Original Publishing Viral Superstar,” National Constitution Center, January 10, 2023, https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/thomas-paine-the-original-publishing-viral-superstar-2. This population figure didn’t include slaves or natives.

14. Thomas Paine, Common Sense (London: Penguin, 1982), 63.

15. Gary Burton, “Thomas Paine and the Declaration of Independence,” Thomas Paine National Historical Association, https://www.thomaspaine.org/pages/resources/thomas-paine-and-the-declaration-of-independence.html.

16. Nelson, “Thomas Paine and the Making of Common Sense,” 239.

17. Harvey J. Kaye, Thomas Paine and the Promise of America (New York: Hill & Wang, 2005).

18. Friedrich Von Gentz, The Origin and Principles of the American Revolution Compared with the Origin and Principles of the French Revolution (Carmel, IN: Liberty Fund, 2010), 72–73. Original work published in 1800.

19. Paine, Common Sense, 98.

20. Paine, Common Sense, 108–9.

21. Gregory Spindler, “John Adams, Thomas Paine, and the Conflict between Conservative and Progressive Liberalism in America,” Starting Points, November 10, 2023, https://startingpointsjournal.com/john-adams-thomas-pain-and-the-beginning-of-conflict-conservative-and-progressive.

22. Massachusetts Court System, “John Adams, Architect of American Government,” Commonwealth of Massachusetts, https://www.mass.gov/guides/john-adams-architect-of-american-government.

23. Conway, Life of Thomas Paine, vol. 1.

24. Thomas Paine, “The American Crisis, No. 1,” America in Class, https://americainclass.org/sources/makingrevolution/war/text2/painecrisis1776.pdf.

25. Thomas Paine, “The Affair of Silas Deane,” Thomas Paine National Historical Association, https://www.thomaspaine.org/works/essays/american-revolution/the-affair-of-silas-deane.html

26. Carine Lounissi, Thomas Paine and the French Revolution (Chem, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 9.

27. Conway, Writings of Thomas Paine, vol. 1 (London: Putnam, 1908), introduction.

28. Thomas Paine, Rights of Man (New York: G. Vale, 1848), 28.

29. Paine, Rights of Man, 3.

30. Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France (London: Dodsley & Mall, 1790).

31. Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France.

32. Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France.

33. Paine, Rights of Man, 149.

34. Paine, Rights of Man, 30.

35. Paine, French introduction to Rights of Man.

36. Paine, Rights of Man, 9.

37. Paine, Rights of Man, 79.

38. Paine, Rights of Man, 104.

39. Paine, Rights of Man, 104.

40. Ayn Rand, “Man’s Rights,” The Virtue of Selfishness (New York: Signet, 1964), 110.

41. Laxton Visitor Centre, “Laxton—Open Fields Visitor Centre & Working Heritage Village,” August 2, 2023, http://www.laxtonvisitorcentre.org.uk; “A Short History of Enclosure in Britain,” Land Magazine 7 (Summer 2009), https://www.thelandmagazine.org.uk/articles/short-history-enclosure-britain.

42. Paine, Rights of Man, 147.

43. Thomas Paine, Agrarian Justice (London: R. Carlyle, 1819), 8.

44. Paine, Agrarian Justice, author’s inscription, French edition.

45. Social Security Administration, “In-Depth Research: Thomas Paine,” https://ssa.gov/history/tpaine3.html; Social Security Administration, “A Hope of Many Years,” https://www.ssa.gov/history/video.

46. Elihu Palmer, Principles of Nature; or, a Development of the Moral Causes of Happiness and Misery among the Human Species (London: J. Canauc, 1819), 95.

47. “The Trial of Thomas Paine: for a Libel, Contained in The Second Part of Rights of Man, before Lord Kenyon, and a Special Jury, at Guildhall, December 18” (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Library), https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/ecco/004809446.0001.000/1:2.

48. Working Class Movement Library, “Thomas Paine and ‘Rights of Man,’” https://www.wcml.org.uk/about-us/timeline/1791--thomas-paine-writes-rights-of-man.

49. Conway, The Writings of Thomas Paine, vol. 3.

50. “Writer Thomas Paine Is Arrested in France,” History.com, November 13, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/thomas-paine-is-arrested-in-france; Calix Eden, “Thomas Paine: Time to Look Again?,” East Anglia Bylines, October 14, 2023, https://eastangliabylines.co.uk/thomas-paine-time-to-look-again.

51. Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason, edited by Kerry Walters (Buffalo, NY: Broadview Editions, 2011), 45.

52. See “Thoughts on Defensive War,” Pennsylvania Journal, 1775, wherein Paine writes, among other references to religious arguments, “Political, as well as spiritual freedom is the gift of God through Christ.”

53. Paine, Rights of Man, 45.

54. Paine, Age of Reason, 45.

55. Paine, Age of Reason, 41.

56. Paine, Age of Reason, 90.

57. Paine, Age of Reason, 106.

58. Paine, Age of Reason, 64.

59. Paine, Age of Reason, 106.

60. Thomas Paine, “The Existence of God: A Discourse at the Society of Theophilanthropists, Paris” (1801), https://www.thomaspaine.org/works/essays/religion/the-existence-of-god.html.

61. Paine, Age of Reason, 65–74.

62. Paine, Age of Reason, 45.

63. Paine, Age of Reason, 50. In the context of Paine’s ideas, I interpret “a thing which everybody is required to believe” to mean “a thing which one expects everyone to believe,” not “a thing which everybody must be forced to believe.”

64. Paine, Age of Reason, 82.

65. Paine, Age of Reason, 113.

66. Patrick Wallace Hughes, “Antidotes to Deism: A Reception History of Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason, 1794–1809” (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 2013), 13–14.

67. Conway, Writings of Thomas Paine, vol. 4 (London: Putnam, 1908).

68. “Age of Reason by Thomas Paine,” USHistory.org, https://www.ushistory.org/paine/reason.

69. Alyce Barry, “Thomas Paine, Privateersman,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 101, no. 4 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, October 1977), 451–61.

70. Conway, Life of Thomas Paine, vol. 2.

71. Robert Ingersoll, The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, vol. 11, 227–28.