As a young girl, I was a multi-library-card carrying bookworm. I read every fiction book I could get my little hands on—exploring the shelves of public libraries, my grandparents’ homes, and the school library, not to mention eagerly awaiting those precious rectangular treasures that would appear under the Christmas tree. The characters in novels became my friends, heroes, and teachers. When I faced challenges, I often looked back on the characters I’d loved to help me make the right choices.

I’m far from alone in my love of fiction. Most people have connected deeply with a work of fiction at some point in their lives, be it a novel, movie, play, short story, comic, TV show, video game, or poem. We connect with stories because they dramatize things we care about: love, friendship, achievement, courage, heroism, intelligence, and so on. Well-crafted works of fiction show us our abstract values in vivid color. They show us we aren’t alone in caring about the things that matter to us; that others see what we aspire to and admire it, too. They also offer new ideals to which we can aspire. This is at once comforting and empowering—providing spiritual fuel, a vision to strive for, and heroes to emulate.

Among the most important values great fiction illustrates is individualism, as opposed to collectivism. Individualism is the idea that the individual is the unit of moral concern, and one cannot morally trample a single person’s life or rights, no matter the supposed benefit to others. Collectivism, by contrast, is the idea that some sort of group (the race, the nation, society, or the like) is the source of moral value, and a single individual’s life is secondary—or irrelevant—compared to the supposed welfare of the group. Both ideas have serious consequences for human life.

Collectivism may manifest merely at the cultural level or at the political level, with the latter being most virulent. The 20th century, for example, was full of collectivist political leaders: Joseph Stalin, Mao Tse-tung, Benito Mussolini, and Adolf Hitler all were rabid collectivists, to name a few of the most significant. They explicitly held that the group comes first—and they enforced this view on entire populations. Hitler wrote, “It is thus necessary that the individual should finally come to realize that his own ego is of no importance in comparison with the existence of the nation, that the position of the individual is conditioned solely by the interests of the nation as a whole.”1 Similarly, a communist, according to Mao Tse-tung, “should be more concerned about the Party and the masses than about any individual, and more concerned about others than about himself.”2 Such ideas caused the death of millions and the misery of millions more.3

By contrast, as Ayn Rand put it, “Individualism regards man—every man—as an independent, sovereign entity who possesses an inalienable right to his own life, a right derived from his nature as a rational being.”4 Individualism, the philosophic underpinning for the political concept of individual rights, influenced the Enlightenment and the subsequent creation of the United States. For example, John Locke, a major influence on the American founding fathers, argued that “being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, liberty, or possessions.”5 In other words, everyone should be free to pursue his own values, so long as he doesn’t violate another’s right to do the same. We can see the practicality of individualism on one level by observing the flourishing it has enabled wherever and to whatever extent it’s been implemented. And the practicality of individualism at the social level is undergirded by its morality at the personal level: It recognizes and upholds the moral fact that each individual’s life is his to live, and the products of his efforts belong to him.

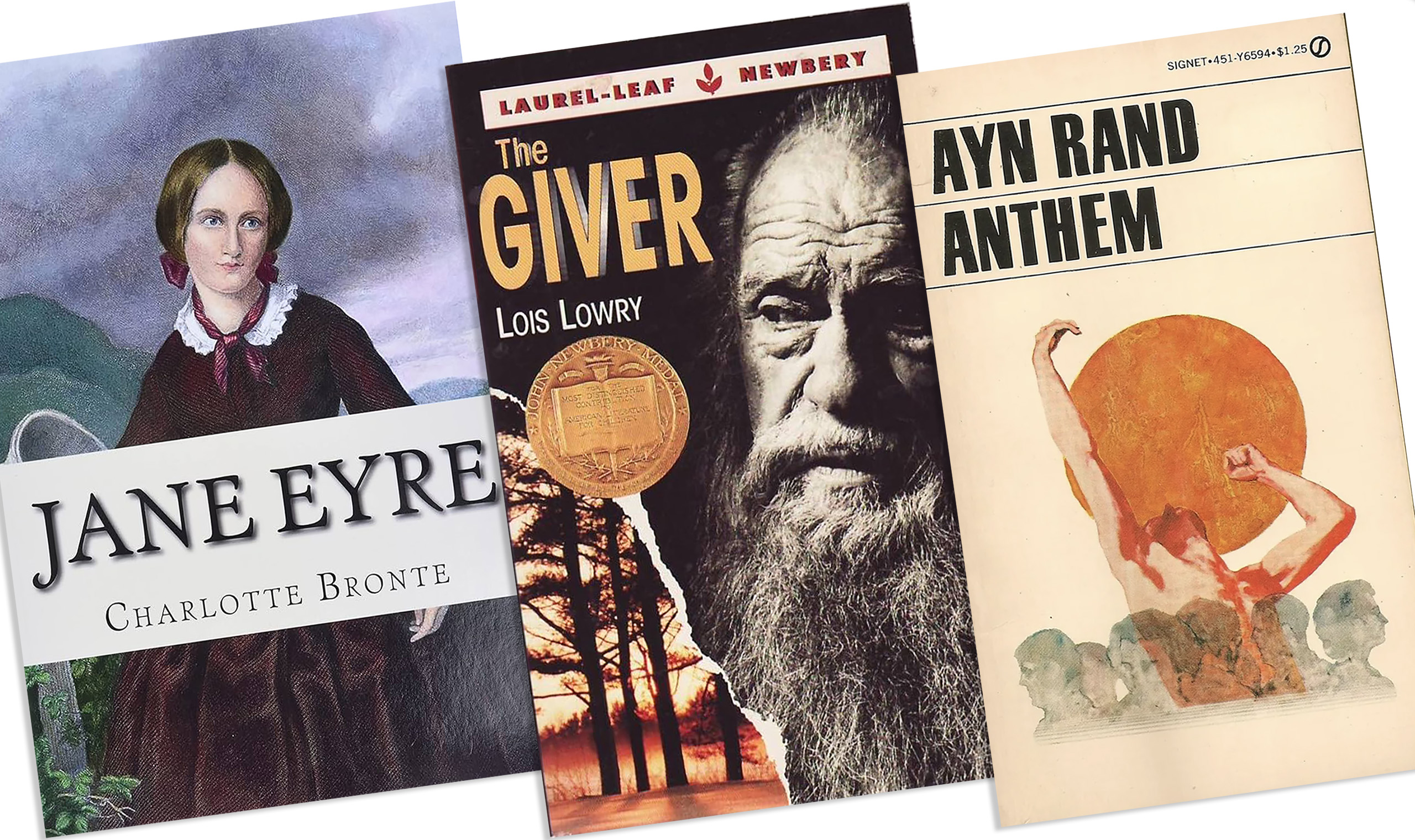

Many literary works depict individualist heroes struggling against collectivist societies, but three brilliant examples are Charlotte Brönte’s classic Jane Eyre, Lois Lowry’s award-winning young-adult novel The Giver, and Ayn Rand’s dystopian novella Anthem.6 By reading these and other such works, we can not only savor them as great works of art, but also gain valuable examples of what it means to live for one’s own happiness—examples we can come back to when facing pressures to sacrifice our values for the supposed good of some collective, whether community, nation, race, or any other group.

Jane Eyre

This timeless novel tells the story of the orphaned Jane, who becomes a strong, intelligent, independent young woman despite the struggles of her youth. . . .

Click To Tweet

You might also like

1. Adolf Hitler, quoted by Leonard Peikoff, The Ominous Parallels (New York: Penguin, 1982), 13.

2. Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung (“The Little Red Book”), trans. David Quentin and Brian Baggins, Marxists Internet Archive, 2019, https://www.marxists.org/ebooks/mao/Quotations_from_Chairman_Mao_Tse-tung.pdf.

3. To be clear, it is not collectivism when a group, such as a sports team or a band, merely works together to achieve a goal. If everyone joins the group voluntarily, then the group members are not putting the group above their own lives and values but prioritizing a shared goal over other, less important goals. For a literary example, consider the fellowship in The Lord of the Rings: Nine characters band together to bring the Ring of Power to Mordor. They share both this specific goal and its deeper purpose—to weaken the evil Sauron, who wants to enslave all of Middle Earth. The members of the fellowship risk their lives to achieve this goal—because they believe that the deeper goal (living freely) is necessary for their greatest values (their lives). Tolkein’s heroes are acting on the principle of individualism. See J. R. R. Tolkein, The Lord of the Rings (Boston: Mariner, 2004), book two.

4. Ayn Rand, The Virtue of Selfishness (New York: Signet, 1964), 150.

5. John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (Overland Park, KS: Digireads, 2009), 73.

6. I do not claim these are the best examples of individualism in great literature, but they are three I am familiar with and that I think portray the ideas particularly well.

7. Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre (Seattle: Amazon Classics, 2017), 234.

8. Brontë, Jane Eyre, 133.

9. Brontë, Jane Eyre, 43.

10. Brontë, Jane Eyre, 209.

11. The more well-known (and perhaps more apt) version of this line comes from the movie adaptation of this book: “It takes a great deal of bravery to stand up to your enemies, but a great deal more to stand up to your friends”; see J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (New York: Scholastic, 1997), 306.

12. Brontë, Jane Eyre, 168.

13. Brontë, Jane Eyre, 264.

14. Lois Lowry, The Giver (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1993), 58.

15. Lowry, The Giver, 65.

16. Lowry, The Giver, 153.

17. Lowry, The Giver, 123.

18. Lowry, The Giver, 123.

19. Ayn Rand, Anthem (Signet: New York, 1995), 21.

20. Rand, Anthem, 97.

21. I have cut out identifying information to eliminate spoilers; Brontë, Jane Eyre, 269.

22. Rand, Anthem, 94.

23. Brontë, Jane Eyre, 31.

24. Lowry, The Giver, 97.

25. Rand, Anthem, 23.

26. Brontë, Jane Eyre, 238.

27. Brontë, Jane Eyre, 35.

28. Lowry, The Giver, 142 (emphasis added).

29. Rand, Anthem, 96.

30. Brontë, Jane Eyre, 167.

31. Rand, Anthem, 95–96.