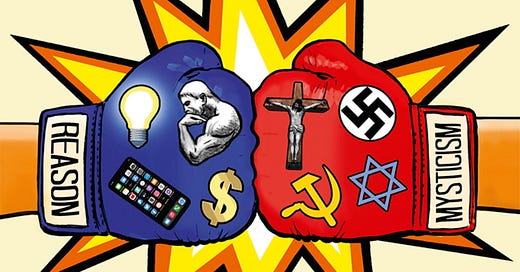

Reason vs. Mysticism: Truth and Consequences

Mystics of all varieties want you to pretend that their pretense is not pretense. Do yourself—and them—a favor: Don’t pretend for them.

How do we know what is true or false, good or bad, right or wrong? What is our means of knowledge?

Our answers to these questions are the most consequential of all. They underlie and affect everything we think, say, and do. They determine the ideas we accept and reject, the plans we make, the actions we take, what we support, and whom we enable. They determine the course of our lives and the course of our culture, for better or worse.

Is knowledge a product of reason, observation, and logic? Is it a product of religious faith or social consensus? Is it acquired through a mixture of these—or perhaps some other means?

Toward answering these questions, we will look first at reason, its key components, and how they work. Then we will consider two forms of mysticism (i.e., claims to a means of knowledge other than reason) along with arguments in support of each: (1) the claim that religious faith is a means of knowledge, and (2) the claim that social consensus is a means of knowledge.

Reason and How It Works

Reason, as the philosopher Ayn Rand observed, is the faculty that identifies and integrates the material provided by man’s senses.1 It operates by means of perceptual observation, conceptual integration, and logic.

In using reason, we perceive things, such as rocks, roses, people, and birds—and we observe their qualities and actions, such as hardness, redness, speaking, and flying. We mentally integrate our observations into conceptual abstractions, such as “rock,” “bird,” “speak,” and “fly”—and we integrate our concepts into increasingly abstract concepts, such as “animal,” “life,” “inanimate,” and “mortal.”

We further integrate our concepts into propositions and generalizations, such as “roses can be red,” “rocks are inanimate,” and “animals are mortal”—and into principles, such as “living things must take certain actions in order to remain alive” and “people must acquire knowledge in order to live.”

By enabling us to mentally integrate our perceptions into abstractions (concepts, generalizations, etc.), reason enables us to acquire, retain, and use a vast network of observation-based conceptual knowledge—from the principles of hunting to those of biology, to those of physics, engineering, art, and psychology.

Of course, human beings are fallible; we can err in our thinking. So, in order to correct any misconceptions or errors we might make, we must check our ideas for correspondence to reality. Our touchstones for this are the basic laws of nature: the laws of identity and causality.

The law of identity is the self-evident truth that everything is something specific; everything has properties that make it what it is; everything has a nature: A thing is what it is. (A rose is a rose; a woman is a woman.) The law of causality is the law of identity applied to action: A thing can act only in accordance with its nature.2 (A rose can bloom, it cannot speak; a woman can become an engineer, she cannot become a pillar of salt.) Insofar as our thinking is consistent with the laws of identity and causality, our thinking is grounded in reality; insofar as it is not, it is not. Our method for checking our ideas for compliance with these laws is logic, the method of non-contradictory identification.3

The basic law of logic is the law of non-contradiction, which is the law of identity in negative form: A thing cannot be both what it is and what it is not at the same time and in the same respect.4 (A rose cannot simultaneously be a non-rose.) The law of non-contradiction is the basic principle of rational thinking. Because a contradiction cannot exist in nature—because things are what they are—if a contradiction exists in our thinking, then our thinking is mistaken and in need of correction. (If we believe that a bush spoke or that a woman turned into a pillar of salt, then we need to correct our thinking).

Reason also enables us to use concepts for engaging in fantasy. We can pretend for the sake of fun or enjoyment that reality is other than it is—for instance, when we read science fiction or play Dungeons and Dragons. We also can pretend that reality is other than it is in an effort to “get away” with something we know we shouldn’t do—such as when a bank robber pretends that other people’s money belongs to him. Further, reason enables us to distinguish between these two types of pretending (fantasy and immorality) and to form concepts for identifying the state of mind of an adult who is unable to make the distinction (e.g., schizophrenic) or unwilling to do so (dishonest).

Reason is astonishingly powerful. It is why human beings have achieved so much and continue to achieve more and more. Consider modern agriculture, shipping, and food production; atomic theory, fracking, and energy production; air and space travel; symphonies and sculptures; COVID vaccines and radiation treatment; satellites, the internet, Zoom meetings—all such values are made possible by reason.

“Knowledge,” as Ayn Rand defines it, is “a mental grasp of a fact(s) of reality, reached either by perceptual observation or by a process of reason based on perceptual observation.”5

Reason is our means of knowledge and our basic means of living. It works. We can see that it works. And we can see how it works. It works by means of identifiable sense organs and methods—including our eyes and ears, conceptual integration, and logic.

Now let’s consider the claim that faith is a means of knowledge.

Religious Faith as a Means of Knowledge

According to the three major monotheistic religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, faith is a means of gaining knowledge apart from or against evidence and logic.

Understanding the distinction between reason and faith is crucial, so I want to emphasize it from a few perspectives.

When a person accepts ideas on the basis of evidence and logic, he is accepting them by means of reason. When he accepts ideas on faith, he is accepting them in the absence of evidence or in defiance of logic. We have the two different concepts—reason and faith—so that we can differentiate between these two different ways of accepting ideas.

What one can know by reason is limited to that for which there is evidence. What one (allegedly) can know by faith is not limited. For instance, on the premise that faith is a means of knowledge, a person can “know” that a woman turned into a pillar of salt—even though (a) no evidence supports the idea and (b) the idea defies the laws of nature and logic. Likewise, on this premise, a person can “know” that a bush spoke, that a stick turned into a snake, that the Earth is only six thousand years old, or that seventy-two virgins await those who die fighting for Allah.

Because faith rejects the need for evidence and logic, a person of faith can “know” literally anything to be true. The following observations and integrations will bear this out.

“Faith,” according to the Bible, “is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.”6 As Rabbi Abraham Heschel puts it, faith is a way of grasping truths that are “beyond our rational discerning,” beyond what “either reason or perception is able to grasp.”7

Given that faith does not operate by means of reason or perception, how exactly does it work? When we use reason, we receive data from external reality by means of our senses. We see by means of our eyes, hear by means of our ears, touch and feel by means of our skin and nerves. Our sense organs are our points of direct contact with reality. They are where and how the basic data of knowledge comes in. When someone “knows” by means of faith, what organ receives the data?

Islamic scholar Abdullah Yusuf Ali explains: “Faith is belief in things which you do not see with your eyes but you understand with your spiritual sense.”8 What is your “spiritual sense”? Rabbi Heschel elaborates: It’s the sense that pertains not to the truth of perceptual reality, but to “the truth of an invisible reality,” a reality “man’s physical sense does not capture, yet the ‘spiritual soul’ in him perceives.”9

In other words, your “spiritual sense” is an extra, non-physical sense—a form of “extrasensory perception” or ESP—a sense that functions by means of no physical organ.

And what is the purpose of this “spiritual sense”? What does it do for you that reason and your physical senses do not? It enables you to believe in the existence of God and to obey his (alleged) commandments. Rabbi Heschel explains: “Just as clairvoyants may see the future” by means of their mystical powers, so, too, people of faith can grasp “the presence of God” and the imperative “to obey His rules and commandments” by way of their “spiritual sense.”10

What kind of rules and commandments does this “spiritual sense” enable people of faith to “understand” and obey? A biblical example is the commandment God issued to Abraham: “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and sacrifice him there as a burnt offering.”11 That order, of course, does not make any rational sense. Why should a man kill his beloved son? But pointing out that an “understanding” received by the “spiritual sense” doesn’t make rational sense misses the point of faith.

The fact that the “spiritual sense” may deliver “truths” or “commandments” that don’t make sense from a rational perspective is, according to people of faith, irrelevant. “Where the act of faith takes place,” Rabbi Heschel explains, “is beyond all reasons. . . . Nobody can explain rationally why he should sacrifice his life and happiness for the sake of the good. The conviction that we must obey [God’s] ethical imperatives is not derived from logical arguments. It originates in an intuitive certitude, in a certitude of faith.”12

Now that we have a more fleshed-out idea of what faith is and how it supposedly works, let us ask a pressing question: What reason is there to accept faith as a means of knowledge? Why should people accept the idea that truth can be grasped by non-sensory, non-rational means?

Saint Thomas Aquinas answers: People “ought to believe matters of faith, not because of human reasoning, but because of the divine authority.” And why should people accept “the divine authority”? More to the point: Why should people accept the existence of a “divine being” in the first place? Aquinas answers: “In order that men might have knowledge of God, free of doubt and uncertainty, it was necessary for divine truths to be delivered to them by way of faith, being told to them, as it were, by God Himself who cannot lie.”13

That, of course, is a circular argument. It commits the logical fallacy of question begging or circular reasoning (i.e., assuming the point at issue, in an attempt to prove it).14 But such logical errors do not faze people of faith, because by accepting faith as a means of knowledge, they reject the principles of logic.

Theologian and pastor John Calvin attests to this:

Our conviction of the truth of Scripture must be derived from a higher source than human conjectures, judgments, or reasons; namely, the secret testimony of the Spirit. . . . God alone can properly bear witness to his own words. . . . The same Spirit, therefore, who spoke by the mouth of the prophets, must penetrate our hearts, in order to convince us that they faithfully delivered the message with which they were divinely entrusted.15

The devoutly religious philosopher René Descartes provides another example, with the added twist of openly acknowledging the circularity of his argument and the fact that people of reason will not accept it:

It is of course quite true that we must believe in the existence of God because it is a doctrine of Holy Scripture, and conversely, that we must believe Holy Scripture because it comes from God; for since faith is the gift of God, he who gives us grace to believe other things can also give us grace to believe that he exists. But this argument cannot be put to unbelievers because they would judge it to be circular.16

Indeed, they would.

To accept faith as a means of knowledge is to undermine (and ultimately reject) reason along with all of the principles that attend it—including the need of evidence, the laws of logic, the method of science. If someone accepts the idea that he can know by means of faith, he thereby rejects the need of evidence and logic in support of knowledge. Conversely, if a person requires evidence and logic in support of knowledge, he thereby rejects the notion that anyone can know anything by means of faith. Thus, for people to maintain that faith is a means of knowledge, they must not allow the principles of reason to interfere with their project. An 18th-century Historical and Critical Dictionary explained:

Since the mysteries of religion are of a supernatural order, they cannot and must not be subjected to the rules of natural light. They are not made for being exposed to the test of philosophical disputations. Their greatness and sublimity forbid them to undergo this ordeal. It would be contrary to the nature of things that they should come out from such a combat as the victors. Their essential character is to be an object of Faith, not an object of Scientific Knowledge. . . . A disputation conducted exclusively in the light of our natural human intelligence will always end unfavourably for the theologians.17

The theologians are well aware of this.

Rabbi Heschel insists, “Reason is not the measure of all things, not the all-controlling power in the life of the man, not the father of all assertions. . . . Logical plausibility does not create faith nor does logical implausibility refute it.”18

Theologian and priest Martin Luther has more choice words for reason. It is, he says, “The Devil’s bride” and “God’s worst enemy”:

There is on earth among all dangers no more dangerous thing than a richly endowed and adroit reason, especially if she enters into spiritual matters which concern the soul and God. For it is more possible to teach an ass to read than to blind such a reason and lead it right. . . . Reason must be deluded, blinded, and destroyed. . . . Faith must trample under foot all reason, sense, and understanding, and whatever it sees it must put out of sight, and wish to know nothing but the word of God.19

We’ve seen what faith is. We’ve heard its advocates acknowledge that it involves no identifiable apparatus or means of operation, save a so-called “spiritual sense,” which amounts to clairvoyance or ESP. And we’ve heard what defenders of faith have to say about reason.

Now let’s take seriously this question: What would it mean genuinely to embrace faith as a means of knowledge—and to advocate that others do so, too? What would it mean in practice?

If we accept the idea that faith is a means of knowledge, we thereby accept the notion that people can “know” literally anything to be true:

If a person has faith that he should love his neighbor, then he knows he should love his neighbor.

If he has faith that he should love his enemies, then he knows he should love his enemies.

If he has faith that he should turn the other cheek if someone strikes him, then he knows he should do so.

If he has faith that he should kill his son if God commands it, then he knows he should do this.

If he has faith that he should convert or kill unbelievers in obedience to Allah, then he knows he should do that.

And so on.

You see the breadth and depth of the problem.

This is why people of faith have been slaughtering each other—and slaughtering people of reason—for centuries. The Middle Ages were fraught with misery and bloodshed because of people’s faith-based obedience to an alleged God’s will. The Crusades entailed the massacre of tens of thousands of men, women, and children because people had faith that those of the wrong faith must die. In faith-based compliance with an alleged God’s will, priests and soldiers of the Inquisition imprisoned, tortured, hanged, gored, or burned tens of thousands of “heretics.” (Victims included the astronomer Giordano Bruno, who was burned alive for the “heresy” of thinking, and the scientist Galileo, who was sentenced to life under house arrest for defying the Church by reporting the truth.) The Thirty Years’ War was thirty uninterrupted years of Protestants and Catholics slaughtering each other over whose “spiritual sense” got things right. Christians in 17th-century Massachusetts held “witch” trials and hanged or crushed to death those whom their “spiritual sense” deemed “guilty.” Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against author Salman Rushdie, ordering his execution for “insulting” Allah in his novel The Satanic Verses, because Muslims have faith that their alleged God wants them to kill anyone who insults him. Osama bin Laden ordered jihadists to hijack commercial airliners and crash them into skyscrapers full of people because bin Laden and the jihadists had faith that Allah exists and wants Muslims to kill unbelievers. In the so-called “Holy Land” in the Middle East, people of faith have been at war since religion began, slaughtering each other for having the wrong “spiritual sense.” Religious disputes between Eastern Orthodox Christians, Roman Catholics, and Muslims are at the core of centuries of faith-based hatred and slaughter in the Balkans. In Afghanistan, the Taliban regularly beat, jail, and murder people for breaking the faith-based laws of Islam. (The punished include women for holding a job or exposing their ankles, men for failing to wear a beard, homosexuals for existing, and anyone for partaking in activities such as playing music, dancing, playing soccer, playing cards, taking photographs, or flying a kite.) And Muslims throughout the world declitorize young girls and make them “marry” old men because they “know” that this is moral.

Should we support these practices? The question is absurd. Yet if we accept faith as a means of knowledge, we do support them.

Either faith is a means of knowledge, or it is not. If it is, then whatever people have faith is true is by that fact true—and whatever they have faith they should do, they know they should do. Contrary to the tired bromide, “If there is no God, anything goes,” the fact is: If faith is a means of knowledge, anything goes.

Fortunately, every thinking adult knows, on some level, that faith is not a means of knowledge. This is why (rational) parents and teachers tell children to look at reality, to use their minds, to think. For instance, they tell children to look both ways before crossing the street, to think about where they’re going, what they’re doing, and what things are. They never tell children to close their eyes and use their “spiritual sense” to determine whether cars are coming, or the sum of two and two, or the elements that make up water, or the theme of a novel. The fact that everyone knows on some level that faith is not a means of knowledge is also why anyone who genuinely tries to determine whether an argument (such as the one I’m making here) is valid or invalid does so not by using his “spiritual sense” but by asking himself whether the argument is supported by evidence, whether it makes logical sense, and whether he can detect any contradictions in it.

Unfortunately, some people pretend that faith is a means of knowledge even when they know it is not. But to “get away” with this pretense, they need help.

In order to feel less guilty about their pretense, those who pretend that faith is a means of knowledge seek psychological support from others. They need others to pretend that their pretense is not pretense so that they will feel absolved of it. Ayn Rand called the seeking of such support “compound second-handedness,” and this is an important and useful phenomenon to understand.

Whereas regular second-handedness consists in treating the views or opinions of other people as more important than one’s own perception of reality and the judgment of one’s own mind, compound second-handedness consists in pretending that facts are other than they are, knowing the nature of one’s action, expecting others to fake their judgment of it, and accepting their faked judgment as a vindication of one’s pretense.20

When someone tries to get you to pretend that his pretense is not pretense, he is engaging in compound second-handedness. Do yourself—and him—a favor: Don’t pretend for him. Tell him that you know that faith is not a means of knowledge, that you know that he knows it, too, and that pretending faith is a means of knowledge is one of the most destructive and immoral things a person can do.

He might not thank you right away. But he might thank you someday. In any event, you will have spared him support of a vice that harms his life and that is responsible for unfathomable cruelty, suffering, and death.

Let’s turn now to another form of mysticism, the notion that social consensus is a means of knowledge.

Social Consensus as a Means of Knowledge

The idea that “social consensus is a means of knowledge” or that “agreement of the group determines what’s true and what’s right” has a long and complex history. But postmodernist philosopher Richard Rorty sums up the idea quite neatly: “There’s no court of appeal higher than a democratic consensus.”21

Of course, we can learn from other people, and we can work with others to acquire knowledge, discover truths, or check the veracity of our conclusions. But this is not what is meant by the claim that “social consensus is a means of knowledge.” When we learn from others, we use our own mind to determine whether their ideas, arguments, or claims make logical sense to us based on our own perceptions of reality. Likewise, when we collaborate with others to acquire knowledge, discover truths, or check the accuracy of conclusions, each person involved uses his own mind to determine what the facts are, what the evidence says, what is or isn’t true. As Ayn Rand put it,

The mind is an attribute of the individual. There is no such thing as a collective brain. There is no such thing as a collective thought. An agreement reached by a group of men is only a compromise or an average drawn upon many individual thoughts. It is a secondary consequence. The primary act—the process of reason—must be performed by each man alone. We can divide a meal among many men. We cannot digest it in a collective stomach. No man can use his lungs to breathe for another man. No man can use his brain to think for another. All the functions of body and spirit are private. They cannot be shared or transferred.22

This view stands in sharp contrast to the idea that there’s no court of appeal higher than a democratic consensus.

Why do “people of consensus” (I’ll use that phrase for ease of identification) regard the ideas of a group as superior to an individual’s perception and judgment of the facts of reality? They make (or rely on) essentially two claims: (1) No one can know reality “as it really is,” and (2) What we call “knowledge” is really “group agreement” or “intersubjective consensus.” We’ll consider these in turn.

No one can know reality as it really is, the argument goes, because man’s sense organs process all incoming data before it reaches consciousness; thus, man is conscious not of an external reality or a world “out there,” but rather of internal processes or modifications.

One of the clearest statements of this idea comes from neuroscientist Sam Harris: “No human being has ever experienced an objective world, or even a world at all,” he writes. “The sights and sounds and pulsings that you experience” are consequences of processed data—data that has been “structured, edited, or amplified by the nervous system.” Thus, “The world that you see and hear is nothing more than a modification of your consciousness.”23

This view is rooted in the ideas of 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who wrote, “What objects may be in themselves, and apart from all this receptivity of our sensibility [i.e., sense perception], remains completely unknown to us.” Once we understand this, Kant says, we “realise that not only are the drops of rain mere appearances, but that even their round shape, nay even the space in which they fall, are nothing in themselves, but merely modifications” of consciousness. In principle, Kant says, the actual object—the object as it really is—“remains unknown to us.”24

It is true, of course, that our sense organs process the data we receive from the external world. But does that mean they distort our view of the world, or that all we perceive are modifications of consciousness?

Let’s put some relevant points in plain language: We have sense organs. They are our points of direct contact with the external world. When our eyes see, they connect with that world. When our ears hear, they connect with that world. When our fingers touch, they touch something real. When we perceive things, it is because our senses connect with things that exist. Those things—whether light, vibrations, liquids, solids, textures, or whatever they happen to be—affect our sense organs as they must, given what those things and our sense organs respectively are (recall the laws of identity and causality). Our sense organs, in turn, react as they must, and this reaction includes transmitting data to our nervous system and brain, which also have specific identities and act accordingly. Our consciousness becomes aware of the data as we perceive the objects by means of this chain of causal connections. The data is real. Our sense organs are real. Our nervous system and brain are real. All of the processing along the way is real. And our perception of reality is real.

Can we err? Of course, we can. But any error we make is not caused by our senses. It is not an error in perception. Our senses give us evidence that something exists. But they don’t tell us what that something is. As Ayn Rand observes, “what it is must be learned by [one’s] mind.”25 Philosopher Leonard Peikoff elaborates:

It is only in regard to the “what”—only on the conceptual level of consciousness—that the possibility of error arises. If a boy sees a jolly bearded man in a red suit and infers that Santa Claus has come down from the North Pole, his senses have made no error; it is his conclusion that is mistaken.

A so-called sensory illusion, such as a stick in water appearing bent, is not a perceptual error. . . . It is a testament to the reliability of the senses. The senses do not censor their response; they do not react to a single attribute (such as shape) in a vacuum, as though it were unconnected to anything else; they cannot decide to ignore part of the stimulus. Within the range of their capacity, the senses give us evidence of everything physically operative, they respond to the full context of the facts—including, in the present instance, the fact that light travels through water at a different rate than through air, which is what causes the stick to appear bent. It is the task not of the senses but of the mind to analyze the evidence and identify the causes at work (which may require the discovery of complex scientific knowledge). If a casual observer were to conclude that the stick actually bends in water, such a snap judgment would be a failure on the conceptual level, a failure of thought, not of perception. To criticize the senses for it is tantamount to criticizing them for their power, for their ability to give us evidence not of isolated fragments, but of a total.26

If we had no sense organs, we would have no means of seeing, hearing, or touching—no means of sensing or perceiving anything. The fact that we do have sense organs—and that they have specific identities and act in accordance with their identities—is not an obstacle to our perception of objects, but the basic means by which we perceive them.

Ayn Rand eloquently summed up the absurdity of Kant’s argument against the validity of the senses and our ability to know reality:

His argument, in essence, ran as follows: man is limited to a consciousness of a specific nature, which perceives by specific means and no others, therefore, his consciousness is not valid; man is blind, because he has eyes—deaf, because he has ears—deluded, because he has a mind—and the things he perceives do not exist, because he perceives them.27

The notion that we can’t perceive reality or know it “as it really is” flies in the face of everything we know and do in our lives. Even so, many modern philosophers and virtually all postmodernists doggedly embrace Kant’s position and restate it ad nauseam:

Professor Stanley Fish writes, “there is nothing that undergirds our beliefs, nothing to which our beliefs might be referred for either confirmation or correction.”28 So, if you pour a cup of coffee, you can’t refer to reality and confirm that you did?

Richard Rorty, channeling philosopher John Dewey, writes, “the idea . . . of an antecedently existing reality . . . the idea that there is a reality ‘out there’ with an intrinsic nature to be respected and corresponded to is not a manifestation of sound common sense.”29 So, it’s contrary to common sense to acknowledge that you are reading these words—and that your acknowledgement corresponds to reality?

Rorty continues: “Nothing grounds our practices, nothing legitimizes them, nothing shows them to be in touch with the way things are.”30 Philosopher Susan Haack responds pricelessly:

Once, at a conference in Brazil, I found myself obliged to make polite small talk with Rorty while we waited for the lecture room in which we were both to speak to open. Thinking the topic suitably neutral, I asked whether his wife had come with him on this trip. No, Rorty replied, she hadn’t; they were bird-watchers, he continued, and Mary only accompanied him when he was going to places where there were birds they had never seen before. I was on the point of exploding: “but, look, you say you don’t believe in ‘the way the world is’; so what could you possibly mean by ‘places where there are birds we have never seen before’?” But luckily, our conversation was interrupted by a pure black hummingbird flying by, and we were able to chat politely about that instead.31

This points to a fallacy identified by Ayn Rand, the fallacy of “concept stealing,” which Kant, Rorty, Fish, Dewey, Harris, and others commit regularly. Concept stealing consists in using an idea or concept while ignoring or denying ideas on which it logically depends.32 To use a concept such as “places” or “are” or “seen”—or any concept that refers directly or indirectly to the existence of reality—while denying the existence of reality is to tear the concept from the context that gives rise to it, the context that connects it to reality, the context that gives it meaning. Susan Haack’s question to Rorty, “what could you possibly mean by ‘places where there are birds we have never seen before’?” (emphasis added), goes right to the point. If there is no reality, or if we can’t know reality “as it is,” then our concepts are just floating abstractions with no real referents, no real meaning. Put another way, to hold that you can’t know reality while nevertheless referring to reality is to contradict yourself.

Even so, Kant, Rorty, Dewey, and company say that we can’t know reality “as it is.” What then can we “know”? What does this thing we call “knowledge” refer to? It refers, they say, to “intersubjective consensus.”

This is the second point that people of consensus make (or rely on) in denying that individuals can know facts of reality.

“Knowledge,” they say (insofar as they use the term) is a product not of the individual’s mind grasping reality, but of group agreement. It is “self-deception,” writes Rorty, to believe “that we know ourselves . . . or anything else” by “knowing a set of objective facts.”33 “Objectivity is a matter of intersubjective consensus among human beings.” To achieve what may be called “knowledge,” he says, one must refer to the “consensus about how things are”—and to do that, “one must use democratic institutions and procedures.”34 In other words, the individual is incapable of knowing on his own. He can “know” only through the collective consciousness of the group.

Indeed, writes Dewey, the individual, apart from the collective, is not even real:

Society in its unified and structural character is the fact of the case; the non-social individual is an abstraction arrived at by imagining what man would be if all his human qualities were taken away. Society, as a real whole, is the normal order, and the mass as an aggregate of isolated units is the fiction.35

Because the group or society “is the fact of the case” and the individual is a mere abstraction, we must refer to the group to determine what is true. We must turn to the collective and see what they agree to. “The best definition” of truth, writes Dewey, is the one posed by philosopher Charles Peirce: “The opinion that is fated to be agreed by all who investigate is what we mean by the truth, and the object represented by this opinion is the real.”36 In other words, truth is a product of social agreement, not individual perception and judgment.

All of this is neatly summed up in Rorty’s maxim: “There’s no court of appeal higher than a democratic consensus.”

Does this idea mean that whatever the majority says is true is, by that fact, true? Yes, that is the basic point. Does it mean that whatever the majority or the powerful decide to do they can legitimately do—regardless of how horrific it might be? It does. Stanley Fish clarifies: In answer to the question, “Does might make right? . . . the answer I must give is yes.”37 Does it mean that there is no fact of reality, aspect of human nature, or objective standard by reference to which we can judge human action at all? It does, explains Rorty: There is no “neutral ground on which to stand and argue that either torture or kindness are preferable to the other.”38 Indeed, writes Rorty:

When the secret police come, when the torturers violate the innocent, there is nothing to be said to them of the form “There is something within you which you are betraying. Though you embody the practices of a totalitarian society which will endure forever, there is something beyond those practices which condemns you.”39

If there is no such thing as truth or knowledge in the sense of the individual perceiving reality, using his mind, generating ideas, and using logic to check them for correspondence to reality—if the individual is merely an abstraction and the group “is the fact of the case”—if all we can “know” is what a “collective consciousness” or “intersubjective consensus” agrees to—then we are in a very bad place. This is cultural relativism, plain and simple.40 And its practical consequences are as horrifying as you might imagine.

As Benito Mussolini explained in 1921, while he was developing the idea of fascism, which he would soon unleash on the world:

Everything I have said and done in these last years is relativism. . . . If relativism signifies contempt for fixed categories and men who claim to be the bearers of an objective, immortal truth . . . then there is nothing more relativistic than Fascist attitudes and activity. . . . From the fact that all ideologies are of equal value, that all ideologies are mere fictions, the modern relativist infers that everybody has the right to create for himself his own ideology and to attempt to enforce it with all the energy of which he is capable.41

Fasces is Latin for “bundle” or “group”; fascism literally means “group-ism.” It regards the group as real, the state as most real, and the individual as an abstraction that is completely subservient to the collective. Having rejected the idea of objective truth, and having embraced the supremacy of the collective over any and all individuals, Mussolini and the Italian fascists set out to remake the world in the image of their ideology. In The Political and Social Doctrine of Fascism (1932), Mussolini wrote:

If the nineteenth century was a century of individualism (Liberalism always signifying individualism) it may be expected that this will be the century of collectivism, and hence the century of the State. . . .

Fascism conceives of the State as an absolute, in comparison with which all individuals or groups are relative, only to be conceived of in their relation to the State. . . . The Fascist State is itself conscious and has itself a will and a personality. . . . The individual . . . is deprived of all useless and possibly harmful freedom. . . .

For Fascism, the growth of Empire, that is to say the expansion of the nation, is an essential manifestation of vitality, and its opposite a sign of decadence. . . . But Empire demands discipline, the co-ordination of all forces and a deeply-felt sense of duty and sacrifice: this fact explains . . . the necessarily severe measures which must be taken against those who would oppose this spontaneous and inevitable movement.42

The Italian fascists enforced their group consensus, attacked their neighbors, and took severe measures against those who resisted. They invaded Greece, murdering eleven thousand individuals and instigating a famine that killed three hundred thousand more. The methods of torture they used on dissidents included extracting their teeth with pliers, dragging them by the tail of a galloping horse, and dousing them with boiling oil.43 They invaded Ethiopia, dropping bombs of mustard gas on civilians, bombing Red Cross camps, shooting resisters, and throwing men, women, and children into concentration camps. They ultimately made Ethiopians submit and join the Empire. The death toll there was more than 382,000.44 They invaded Yugoslavia, where they massacred tens of thousands of men, women, and children, and herded thousands more to their deaths in concentration camps. An Italian soldier wrote home saying, “We have destroyed everything from top to bottom without sparing the innocent. We kill entire families every night, beating them to death or shooting them.”45

The National Socialists followed suit. “Truth” they insisted, is a matter of group consensus—in this case, the consensus of the “Aryan race” or “master race”—and the group has the right to create its own ideology—in this case Nazism—and to enforce it with all the energy of which it is capable. The Nazis proceeded to torture and murder six million individuals—men, women, and children—who belonged to the “wrong” race. The rationale? Individuals do not matter. Only “groups,” “types,” and “kinds” do. And only people of the right “kind” can know the truth of the matter or act accordingly because a person’s knowledge and character are determined by his kind, his race.

Virtually everyone knows about the Nazi’s systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews. Relatively few know about the essence of the Nazis’ philosophy—in particular, their theory of knowledge. Carl Schmitt, a renowned jurist in National Socialist Germany, put it clearly:

A sound theory of knowledge demonstrates that only the person whose character and attitude are determined by his kind race . . . and who actually belongs to the community, is able to see facts in the right way, and to form valid impressions of human beings and things.

In the deepest core of his feelings, and in the smallest fibre of his brain tissue, man stands within the confines of his folk and race. . . . An alien [a person of a different race] may be as critical as he wants to be, he may be intelligent in his endeavour, he may read books and write them, but he thinks and understands things differently because he belongs to a different kind, and he remains within the existential conditions of his own kind in every decisive thought.46

This theory of knowledge was known and propagated throughout the Nazi ranks. Alfred Rosenberg, a leading theorist among National Socialists, said, “The race-soul is the measure of all our thoughts, . . . the final criterion of our values.”47 Otto Wacker, a leading National Socialist in the Ministry of Education, said, “The Negro or the Jew will view the same world in a different way from the German.”48 Philipp Lenard, “Chief of Aryan Physics” under the National Socialists, explained what this means for science: “Science, like every other human product, is racial and conditioned by the blood.” (Lenard and other “Aryan” physicists rejected Albert Einstein’s work because it was “Jewish physics” and thus inferior to “Aryan physics.”)49 And Hermann Goering, a major figure among the National Socialists, explained what this principle means for women: They must, he said, “take hold of the frying pan, dustpan and broom and marry a man.”50

The National Socialists held social consensus, in the form of the “race-soul,” as the source of all Aryan knowledge and values. Everything else the Nazis did—including murdering six million Jews—followed from that.

Marxist Socialists and communists also embrace the notion that truth and knowledge are matters of social consensus. In their case, the relevant “group” or “kind” is one’s economic class. The bourgeois (“middle class”) creates its own truth; and the proletariat (“working class”) creates its own truth; and neither’s truth applies to the other, so class warfare is inevitable until one class is gone.

As Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote in The Communist Manifesto,

Don’t wrangle with us so long as you apply, to our intended abolition of bourgeois property, the standard of your bourgeois notions of freedom, culture, law, etc. Your very ideas are but the outgrowth of the conditions of your bourgeois production and bourgeois property, just as your jurisprudence is but the will of your class made into a law for all, a will whose essential character and direction are determined by the economical conditions of existence of your class.51

What did this theory of knowledge lead to? By conservative estimates, the number of individuals murdered during the 20th century by Marxist socialists and communists for belonging to the “wrong class” and thus not knowing the “right truth” is about 100 million. These include sixty-five million murdered by the Chinese communists, twenty million murdered by the Soviet socialists, and more than two million murdered by the Khmer Rouge (Cambodian communists).52

Each and every one of these victims of collectivism was a real, living, breathing individual human being, with real values, goals, dreams, and loved ones. Each was murdered because people of consensus “knew” that he or she should be murdered. How did they “know”? They embraced social consensus as a means of knowledge.

Now, observe a profoundly relevant fact. The idea that social consensus determines truth is a textbook logical fallacy. It’s the fallacy of appeal to the masses or appeal to the majority. It is fallacious for the simple fact that truth is correspondence to reality, not social consensus. Every thinking adult knows that truth is not a matter of group consensus. We know that societies used to think that the Sun revolves around Earth rather than Earth revolving around the Sun, and we know that this did not make it so. We know that society in the antebellum South agreed that slavery should be legal—we know that some societies in Africa still agree that it should be legal—and we know that this didn’t make it true in the antebellum South and doesn’t make it true in Africa today. Likewise, we know that some people believe or pretend that truth and knowledge are matters of group consensus, and we know that this doesn’t make it so.

People of consensus embrace a logical fallacy as their theory of knowledge. They treat group opinion as the determinant of truth. In doing so, they foster second-handedness as their basic psychological disposition: They look to the group to see what they should think, believe, say, and do. And, having done that, they engage in compound second-handedness—seeking your faked agreement with their pretense that social consensus is the source of truth—in order to assuage their guilt for failing to look at reality, use their minds, and think for themselves.

***

Reason or mysticism: These are our basic alternatives.

One leads to knowledge, production, trade, prosperity, and social harmony. The other leads to ignorance, destruction, plunder, poverty, and unspeakable cruelty.

Reason is the faculty that identifies and integrates the material provided by man’s senses. It is the faculty that enables us to understand reality, the nature of things, and how we can use them to advance our lives, liberty, and happiness. Mysticism includes any claim to a non-sensory, non-rational means of knowledge—whether religious faith, a “spiritual sense,” social consensus, a “race-soul,” clairvoyance, ESP, or any other form of “just knowing.”53 Mysticism is an excuse for any criminal, dictator, collective, or “intersubjective consensus” to “get away” with anything, from robbery to rape to terrorism to genocide.

Mystics of all varieties want you to pretend that their pretense is not pretense. Do yourself—and them—a favor: Don’t pretend for them. Stand firm as a person of reason. Tell them that you know that reason is man’s only means of knowledge, that you know that they know it, too, and that pretending otherwise is one the most destructive and immoral things a person can do.