Author’s Note: This article is a companion piece to my previous portrait of Ingersoll, “Robert Ingersoll: Intellectual and Moral Atlas.” Whereas that article focused primarily on his free-thought legacy, this one focuses on his defense of capitalism.

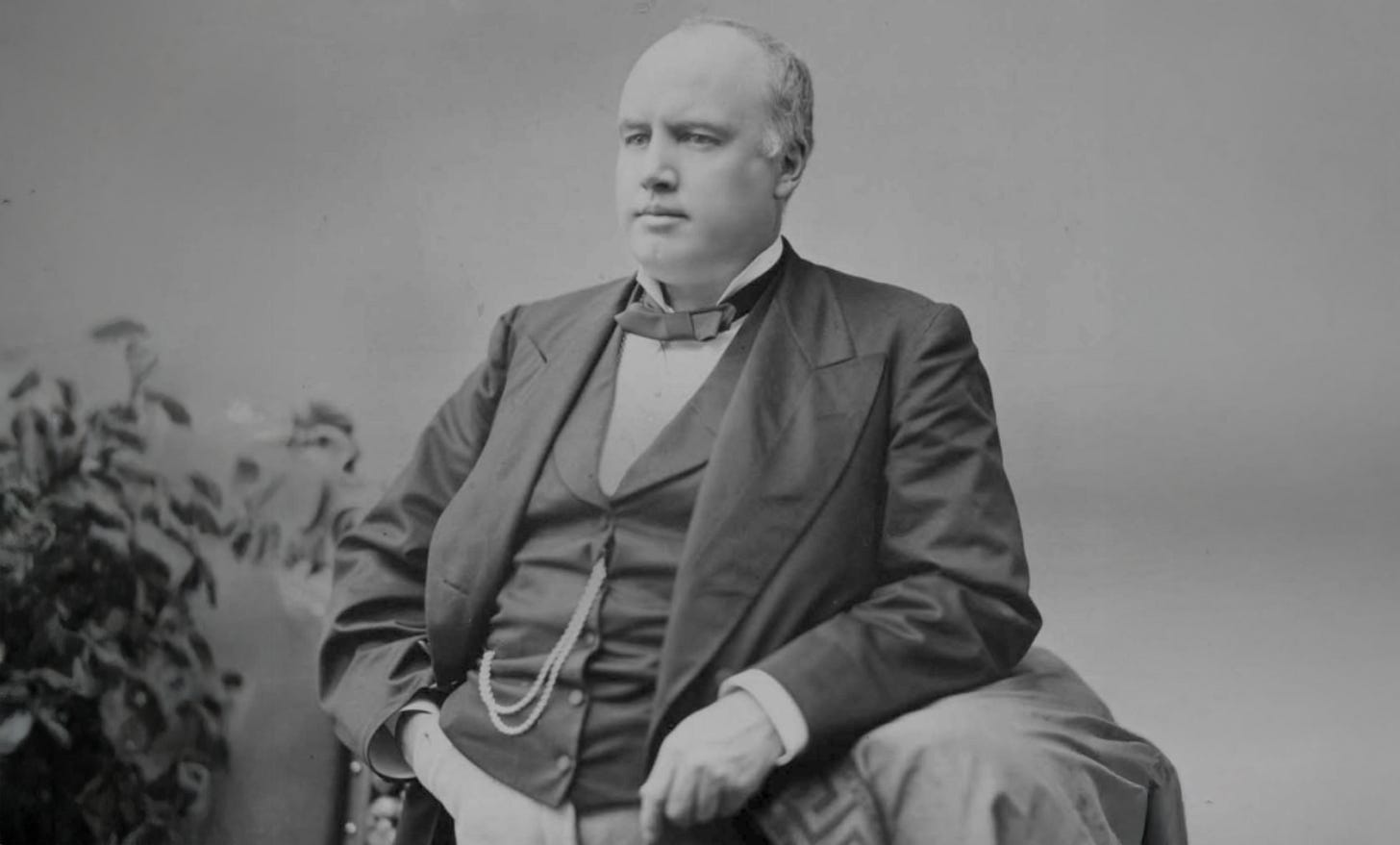

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833–1899), known as “The Great Agnostic,” is widely recognized for his powerful oratory in defense of free thought, secularism, and individual liberty. However, Ingersoll was also a dedicated advocate of capitalism, entrepreneurship, and the American ideal of self-reliance.

Ingersoll was a lifelong Republican during an era when the party generally defended economic liberty and limited government. He was a prominent campaigner for Republican presidential candidates, leveraging his oratorical prowess to support figures such as Maine senator and presidential candidate James G. Blaine. He admired Blaine for his abolitionism, his pro-business stance, and his strength in navigating the difficult Reconstruction period after the Civil War as speaker of the house. He nominated Blaine for the Republican presidential candidacy in 1876 in what became known as the “Plumed Knight” speech:

This is a grand year—a year in which the people call for a man who has preserved in Congress what our soldiers won upon the field. . . . a man who, like an intellectual athlete, stood in the arena of debate, challenged all comers, and who, up to the present moment, is a total stranger to defeat. Like an armed warrior, like a plumed knight, James G. Blaine marched down the halls of the American Congress and threw his shining lances full and fair against the brazen foreheads of every defamer of his country and maligner of its honor. For the Republican party to desert a gallant man now is worse than if an army should desert their general upon the field of battle.1

Although Blaine ultimately lost the nomination to Rutherford B. Hayes, the rousing speech made Ingersoll a sought-after Republican stump speaker. He went on to campaign for Hayes in 1876 and James Garfield in 1880. He supported these candidates because they stood for the party’s post–Civil War goals of Union preservation, economic progress, and limited government, which aligned with Ingersoll’s political priorities as an advocate for individual liberty. He also supported William McKinley during the 1896 campaign, speaking at events such as the massive Chicago rally in October to promote McKinley’s platform of economic prosperity and his advocacy of a gold standard. Through his campaign speeches and political lectures, Ingersoll championed sound money (meaning a stable currency that retains its value over time because it’s backed by a tangible asset such as gold), criticized inflationary policy, and rejected the popular idea that free enterprise conflicted with the welfare of workers.

Ingersoll’s views on capitalism and free markets stemmed from his philosophic commitment to liberty and individual rights. He recognized that economic freedom is inseparable from personal freedom. Just as he sought to protect the right of individuals to think and speak freely, he also sought to protect their rights to work, trade, and create wealth without interference from the state. His defense of capitalism was based not merely on economic efficiency but on moral grounds—he viewed the abilities to create, trade, and prosper as essential expressions of individual liberty. He often called this “the liberty of hand and brain.”2

Defense of the Gold Standard and Sound Money

Ingersoll strongly supported the gold standard, believing that a stable currency backed by tangible value was essential for economic integrity and long-term prosperity. He warned against the dangers of debased currency, arguing that dishonest money (i.e., currency that wasn’t redeemable for gold or silver, such as the “greenbacks” issued during the Civil War) robbed workers and savers of their hard-earned wealth by reducing the purchasing power of their money through inevitable inflation.3 After the Civil War, the national economic debate was about what should serve as the basis for the nation’s money supply and how its value should be maintained. Should it be backed by gold or should it be fiat currency (currency created by government decree)? Although the gold standard was adopted in 1879, the panic of 1893 (which caused bank failures and high unemployment) fueled calls to abandon it and inflate the money supply. Farmers and debtors wanted this to ease debts and boost prices; bankers and industrialists wanted to stick with the gold standard for stability. In his 1896 speech on the currency question, Ingersoll stated,

The government cannot create wealth by printing paper. Every promise made beyond the power of redemption is fraud. Every effort to create value by decree is destined to end in ruin. The worker who receives his wages in honest gold holds in his hand the fruit of his labor—a token the world over of real value. But to give him payment in depreciated paper is to steal from him in the name of the law.4

Ingersoll understood that inflation is not merely an economic issue but a moral one. He viewed it as legalized theft wherein the government diminishes the value of a person’s labor by manipulating the value of currency. To Ingersoll, the gold standard ensured that laborers and entrepreneurs alike were rewarded fairly for their efforts and that wealth retained its relative economic value across generations.

Harmony between Capital Holders and Laborers

Although some of his contemporaries painted business owners and workers as opposing forces in perpetual conflict, Ingersoll rejected this idea. He believed that the interests of workers and entrepreneurs were naturally aligned—when markets are free, and contracts are voluntary. In a speech extolling the mutually beneficial relationship between business owners and employees, he declared,

There is no conflict between capital and labor. Capital is the fruit of labor, and labor is the father of capital. The man who builds a factory gives work to others; the worker who produces wealth creates the capital that funds future labor. They are not enemies but partners, standing together in the creation of civilization and prosperity.5

Ingersoll understood that capitalism is not a zero-sum game in which one party’s gains come at the expense of another. He viewed wealth creation as a mutually beneficial process in which successful entrepreneurs and investors provide opportunities for workers, and industrious workers (including managers) create the value that enables businesses to grow. This harmony, however, depends on the government protecting property rights, enforcing contracts, and not interfering in people’s voluntary transactions.

Praise for Entrepreneurs and Builders

Ingersoll deeply admired the people who created and built industries. He was acquainted with many of them, including Andrew Carnegie, Thomas Edison, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Henry Flagler. Ingersoll saw these men as embodiments of human ingenuity and the American spirit. In a tribute to the country’s industrialists and inventors, he remarked,

The men who have made this country possible, who have built its roads, bridged its streams, and turned the wilderness into wealth—they are not robbers, but builders. They have given work to the idle, homes to the homeless, and raised the standard of life. The cry against them is the cry of envy, not of reason.6

Ingersoll did not romanticize wealth in and of itself; he admired the process of wealth creation and the effort behind productive achievements. He believed that wealth honestly earned through production and trade was a noble achievement, not something to be resented or confiscated. Ingersoll stood firmly in the tradition of classical liberalism, a philosophy rooted in the primacy of individual rights, limited government, free markets, and freedom of thought.

Ingersoll’s secular liberalism sharply contrasted with two other growing forces in that era: Christian nationalism and democratic socialism, represented by figures such as William Jennings Bryan and Eugene V. Debs, respectively. Despite their appeals to justice, both movements ultimately wanted to subordinate the individual to a collective cause through force. Bryan sought to bind politics to religious morality, using the state’s power to impose a Christian vision of virtue on the public. He portrayed the working class as righteous victims, and capitalists as oppressors, famously saying, “You shall not crucify mankind on a cross of gold!”7 Bryan would later face off against Clarence Darrow in the famous 1925 Scopes “Monkey” Trial, portrayed in the film Inherit The Wind.8 As for Debs, though he was a well-meaning advocate for the working class, he embraced a secular Marxist vision of economic equality that called for state control over private property and commerce. He went on to run for president as the Socialist Party candidate five times between 1900 and 1920. Although both men invoked the language of “the rights of the people” and “economic justice,” their movements marked a turn away from the Founders’ vision of individual rights and toward a politics of group identity and coercive redistribution. Ingersoll, by contrast, remained loyal to the American idea that rights belong to individuals—not to classes, creeds, or collectives.

Interestingly, both Bryan and Debs had great admiration for Ingersoll. When Bryan was a young man, he wrote to Ingersoll to ask about his views on God and immortality (he was not comforted by Ingersoll’s reply).9 Despite their political differences, Debs and Ingersoll were friends, and Debs idolized Ingersoll for his “noble character.” Ingersoll viewed Debs as a sincere but misguided “dreamer.” After Ingersoll’s death, Debs wrote to his granddaughter, “I was the friend of your immortal grandfather and I loved him truly. The name of Ingersoll is revered in our home, worshipped by us all, and the date of birth is holy in our calendar.”10

Unlike many reformers of his era, Ingersoll was uncompromising in his defense of liberty across the board—in politics, religion, economics, and speech. He championed the individual’s rights against every form of imposed authority, whether from the church, the state, or the mob.

The Value of Art and Culture

Ingersoll’s admiration for wealth creation included admiration for those engaged in artistic and intellectual pursuits. He recognized that free markets and economic prosperity created the conditions under which art and culture could flourish. He observed that societies that valued property rights and free exchange were more likely to produce great works of art, literature, and music. In his lecture “The Liberty of Man, Woman, and Child,” he said,

Culture is the child of liberty. Where the mind is free, there art and beauty grow; where chains bind thought, there is only barrenness. Art is the blossom of civilization. It softens the heart, refines the mind, and turns the savage into a man. Music is the voice of the soul, the language of all hearts. It lifts us above the dust and tells of infinite hope.11

In Ingersoll’s time, many in the new but growing socialist movement argued that capitalism stifled art and “noble pursuits” by prioritizing profit and fostering a “vulgar materialism.”12 However, Ingersoll recognized that the flowering of art, music, and culture was not opposed to capitalism; these things were natural products of it. Just as the industrialist envisions and creates bridges and factories for material needs, the artist creates works that entertain and inspire, nourishing our souls. Both forms of creation require liberty and the security of property to thrive.

Opposition to Forcible Redistribution of Wealth and Class Warfare

Ingersoll rejected the growing tide of Marxist ideology that depicted society as being embroiled in “class warfare” between irreconcilably opposed camps of rich and poor. He saw efforts to forcibly redistribute wealth through state action as unjust and counterproductive. In one of his more pointed attacks on socialist ideas, he remarked,

The man who has made money by his brain and hands has the right to enjoy it, and you have no more right to take it from him than he has to take your wages from you. Socialism is theft dressed as philosophy. The war of classes is the war of ignorance, and its fruit is misery.13

Ingersoll’s defense of capitalism was ultimately rooted in his defense of individual rights. He saw the right to own property and to enjoy the fruits of one’s labor as a natural extension of one’s right to live freely. Ingersoll understood that any attempt to undermine those rights—whether in the name of equality or fairness, or for any other reason—is a violation of justice. He recognized that political and economic freedom are inseparable—a society that protects freedom of speech and conscience but restricts the rights to trade and to own property would ultimately fail to be free.

Robert Ingersoll’s praise for entrepreneurs, builders, and workers was not only based on economic theory but on a profound moral belief in the dignity of labor and the creative power of human effort. His unwavering support for the gold standard, sound money, and the harmonious relationship between capital holders and laborers reflected his conviction that freedom, prosperity, and justice could only flourish when individuals were able to think, create, and trade freely.

This article is based on Tom Malone’s forthcoming anthology, The Portable Robert Ingersoll, to be released on May 5th.

Robert G. Ingersoll, “Speech Nominating Blaine,” in The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, vol. 9, Political, Dresden Edition (New York: C. P. Farrell, 1902), 137–47.

Robert G. Ingersoll, “The Foundations of Faith,” in The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, vol. 4, Lectures, Dresden Edition (New York: C. P. Farrell, 1902), 258.

A “debased” currency refers to money that has lost value or purchasing power, typically through government money printing or inflation. Gold backing stops currency debasement by tying money’s value to a tangible asset that governments can’t easily manipulate.

Robert G. Ingersoll, “Hard Times and the Way Out,” The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, vol. 9.

Ingersoll, “Eight to Seven: Indianapolis Speech,” in The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, vol. 9, 427–46.

Ingersoll, “Wall Street Speech,” in The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, vol. 9, 447–65.

George Mason University, “Bryan’s ‘Cross of Gold’ Speech: Mesmerizing the Masses,” History Matters, https://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5354.

The 1925 Scopes “Monkey” Trial was a landmark legal case in Tennessee in which teacher John T. Scopes was tried for violating a state law that banned the teaching of evolution, symbolizing the national clash between modern science and religious fundamentalism.

Susan Jacoby, The Great Agnostic: Robert Ingersoll and American Freethought (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 115.

Orvin Larson, American Infidel: Robert G. Ingersoll (New York: Citadel Press, 1962), 278.

Robert G. Ingersoll, “The Liberty of Man, Woman, and Child,” The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, vol. 1 (New York: C. P. Farrell, 1902).

Friedrich Engels, Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy, translated by Austin Lewis, Marxists Internet Archive, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1886/ludwig-feuerbach/index.htm.

Ingersoll, “Wall Street Speech,” The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, vol. 9.

I think the moral defense of capitalism is egoism, and that's based on the moral standard of human life, its maintenance and its improvement.