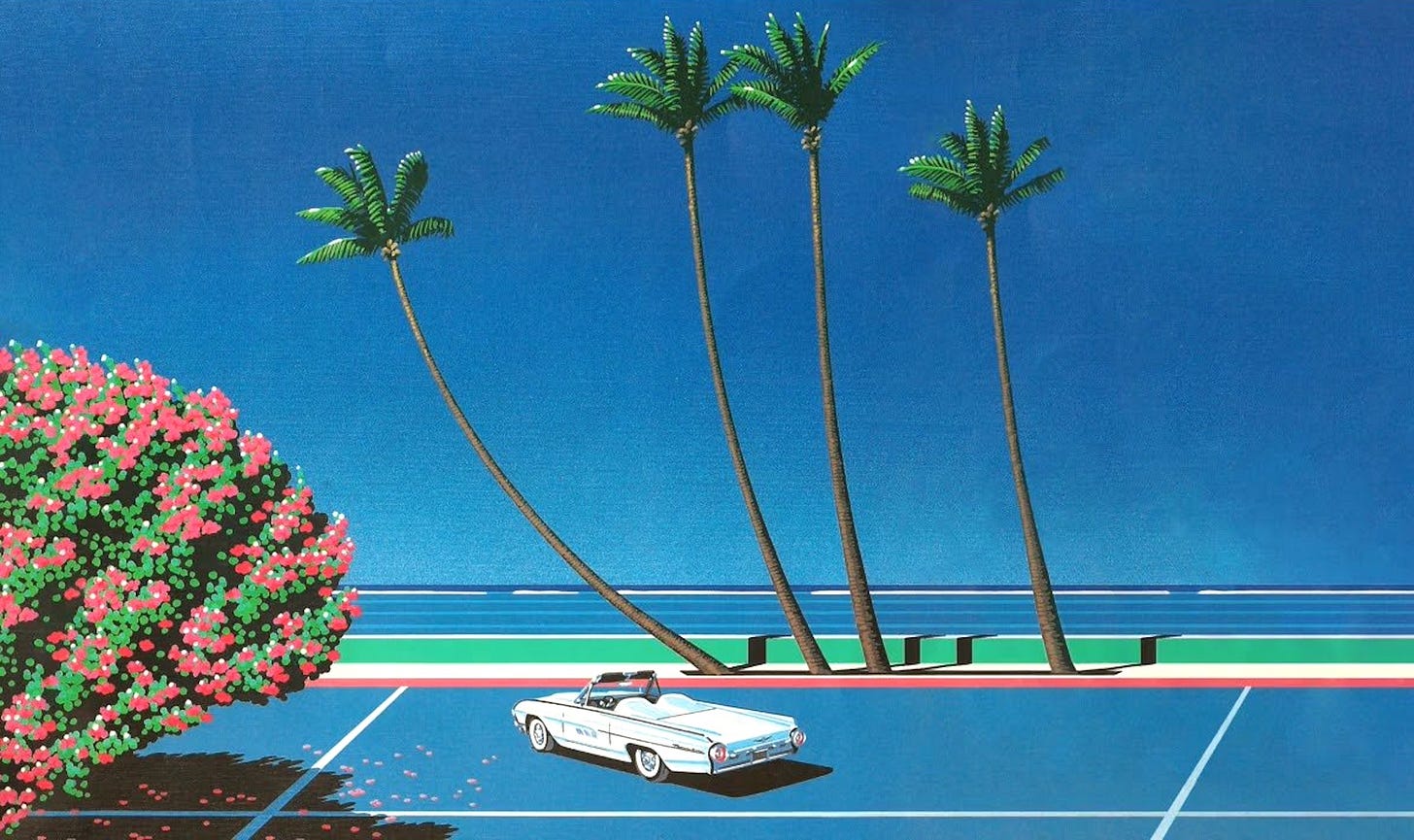

Palm trees, beautiful beaches, vintage cars, sparkling pools, and skyscrapers reaching for an ultramarine, cloudless twilight sky. These all feature in the works of Japanese artist Hiroshi Nagai, whose evocative paintings were used for the covers of many 1980s Japanese pop albums. The somewhat nostalgic, dreamy realism of Nagai’s work has captivated man…

Substack is the home for great culture