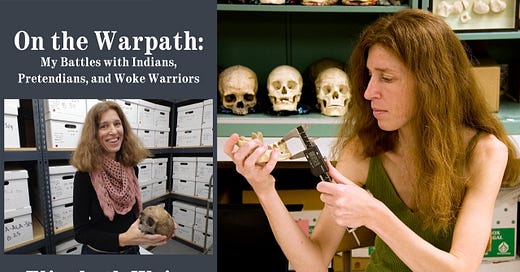

On the Warpath: My Battles with Indians, Pretendians, and Woke Warriors by Elizabeth Weiss

By Timothy Sandefur

Washington, D.C.: Academica Press, 2024

228 pp., $29.95 paperback

According to an old wisecrack, the reason arguments between college professors are often so nasty is that the stakes are so small. But in Elizabeth Weiss’s case, the stakes are nothing less than the destruction of an entire science. In her new memoir, On the Warpath, she reveals how anthropology is slowly being sacrificed for the sake of that toxically irrational sludge of ideologies collectively known as “wokeness.”

Her story begins in 1990 with the enactment of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, a federal law that governs collections of objects and human remains held by museums throughout the United States. That law was adopted in response to complaints by Indian tribes that researchers in previous decades had taken bones and artifacts from Native graveyards or tribal land without legal permission, and that many museums were therefore holding items that Native Americans considered stolen property. But rather than confining it to cases of actual theft, NAGPRA’s authors mandated that even in the absence of wrongdoing, skeletons or “associated items” (typically, tokens buried along with the dead) must, if found on federally owned land, be given to officials of the tribe with whom those items are “affiliated.” NAGPRA also requires that museums receiving federal funding (which is virtually every museum in the United States) “repatriate” bones or objects that they’ve held in their collections for decades to “affiliated” tribes—again, regardless of whether any theft actually occurred.

This law, and the regulations that federal bureaucrats have written for implementing it, have emptied museum exhibits, rendered priceless scientific data off-limits to research, and granted special government privileges to the followers of Native religions, contrary to the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause.

Perhaps the most infamous case involving NAGPRA started in 1996 when a nine-thousand-year-old skeleton known as Kennewick Man was unearthed on federally owned land in Washington State. At the time, it was among the oldest skeletons ever found in the western hemisphere, and it was notable for featuring a wound in the leg, apparently caused by an arrowhead. Several tribes claimed Kennewick Man as an ancestor and demanded that the federal government hand it over to be reburied—that is, effectively destroyed, and rendered inaccessible to research. But NAGPRA only lets tribes demand “repatriation” of remains with which they’re “culturally affiliated,” and the skeleton was far older than any current American Indian tribe. That meant no cultural affiliation could be proven, so the bones should not have been subject to the law’s requirements.

Years of litigation nonetheless ensued, during which the skeleton was kept locked away from scientists—although federal officials allowed tribal members to access the bones and even perform religious rituals with them, thereby contaminating them with foreign material and rendering DNA analysis more difficult. Finally, in 2004, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the bones were not subject to NAGPRA. A decade later, however, Congress passed a new law ordering that the skeleton be given to a group of tribes anyway, and they destroyed the specimen in 2017.1

It was in that environment that Dr. Elizabeth Weiss, an idealistic young anthropologist, began what she called her “dream job” at California’s San Jose State University: a professorship that combined classroom teaching with the opportunity to conduct research on the extraordinary collections of ancient human remains at Northern California universities (9). Weiss would eventually learn that the job required her not only to surrender priceless scientific specimens for destruction, but also to stifle criticism of NAGPRA.

Although she obeyed those rules, she teamed up with attorney James Springer to publish a book in 2020 arguing that NAGPRA is unconstitutional and a barrier to crucial research—research that not only can inform us about the human past, but also help us detect and cure diseases today. The First Amendment requires the government to remain neutral between different religions. Given this, it’s almost unimaginable that federal officials would, for example, force museums to give away ancient Christian relics to representatives of the Vatican, or to allow the Chief Rabbinate of Israel to dictate how scientists may handle exhumed relics. Yet NAGPRA does the equivalent of these things, requiring museums and colleges not only to remove content from their collections to satisfy the demands of Native American religionists, but also to include “traditional Indian religious leaders” on committees that write the rules under which their collections are managed (55).

As Weiss observes, “it’s not good enough to have Indian religious leaders [on such committees]; they must be ‘traditional Indian religious leaders’”—meaning that the requirement excludes (for example) Christians, despite the fact that more than 60 percent of Native Americans today identify as Christian (55).2 In fact, the Bureau of Indian Affairs specifically requires that such representatives be “people needed to practice traditional Native American religion”—that is, priests.3 The bottom line, as Weiss puts it, is that “Native American traditional Indian religion is given preferences that no other religion is provided” (50).

Religion is, indeed, what instigates much of the controversy involving NAGPRA. Some Native groups hold that their tribes were created within North America by the gods—that the first humans emerged from the Earth at the behest of Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka (Great Spirit) or were transformed by Áwonawílona (the Maker of All) out of web-footed creatures swimming in the underworld, to cite just a few examples. Many tribes are also hostile to the land-bridge theory most anthropologists hold, according to which humans migrated to North America about thirty thousand years ago through what is now Alaska.

But most of those responsible for implementing NAGPRA, and state-law versions of NAGPRA such as California’s “CalNAGPRA,” don’t hold these religious beliefs themselves. Rather, they’re adherents of postmodernist, anti-reason ideologies according to which Native Americans are spiritually pure due to their being “untainted” by Western civilization. According to this “noble savage” myth—which dates back to Jean-Jacques Rousseau—indigenous peoples are models of moral sanctity, political peace, and ecological harmony with nature. In other words, adherents of this anti-Western ideology view Native Americans not as individuals facing real challenges in contemporary life, but as stereotypes—convenient symbols for everything opposed to capitalism, technology, and the complexities of modern life. As Weiss notes, acolytes of postmodernist mythology are sometimes motivated to be more “Indian” than actual Native Americans themselves—even pretending to be Natives when they aren’t—and taking up what they consider a moral crusade against science and reason in the name of “social justice”—a crusade that does nothing to benefit Native Americans or anyone else.

Weiss’s anti-NAGPRA book was controversial, but San Jose State officials respected her right as a scholar to advance controversial arguments. Her supervisor even wrote a recommendation for the school to give her time off to complete the book, in which he praised her for her “steadfast commitment to advancing reason, rational thought, and the scientific method” (33). The book was positively reviewed in scientific journals, and although there was a burst of outrage on Twitter in the months that followed, the university’s dean assured Weiss that he “strongly supported academic freedom” (63).

That turned out to be untrue. Less than two years later, Weiss organized a panel about NAGPRA at an online conference held by the prestigious Society for American Archaeology. It provoked an explosion of outrage among “woke” participants, including those from such organizations as the Queer Archaeology Interest Group and the Black Trowel Collective, who accused Weiss of racism and labeled her a “grave robber” and a “ghoul” due to her belief in scientific research on ancient remains. The Society swiftly apologized for allowing her to speak and promised not to post the recording of her talk on its website, where it might make some people “feel marginalized” (82, 93).

That incident, along with Weiss’s questioning of San Jose State’s method for counting the number of enrolled Native American students (administrators apparently just made up a number), contributed to a showdown between her and her colleagues that began in June 2021. That’s when Weiss’s supervisor—who only months earlier had lauded her “steadfast commitment to advancing reason, rational thought, and the scientific method”—gave a presentation at an academic conference in which he accused her of “professional incompetence” and called her arguments “racism . . . couched in the language of research” (127, 133). In the months that followed, he and other university administrators searched for ways to ostracize her.

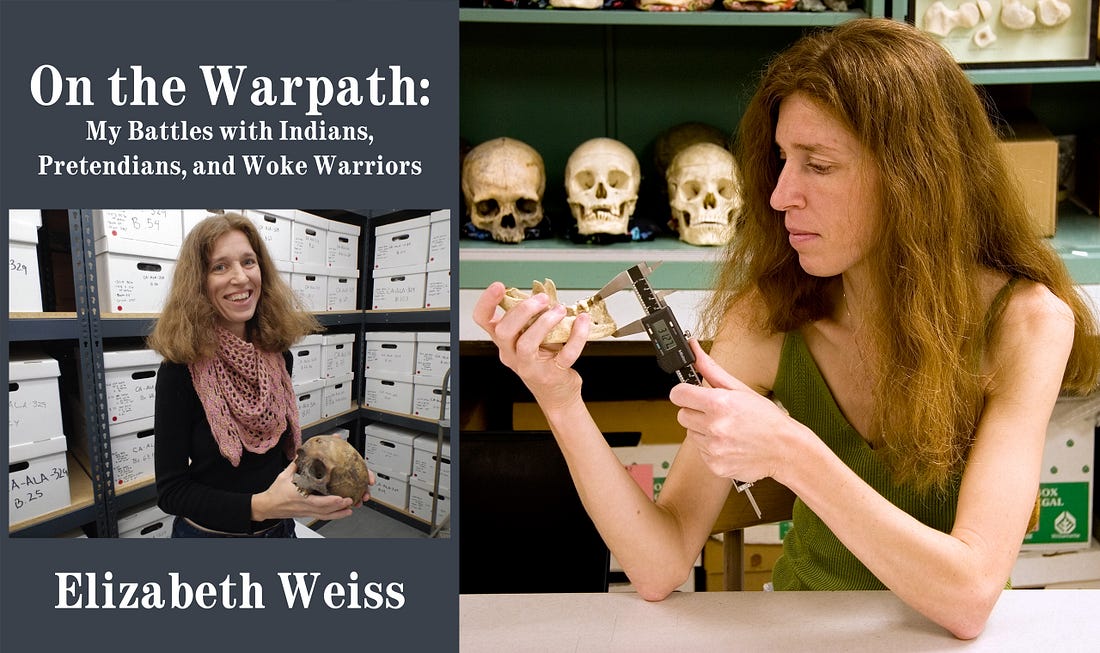

The opportunity came on September 18, 2021, when Weiss posted a photograph on Twitter of herself holding an ancient skull, accompanied by the words “So happy to be back with some old friends” (145). Within days, the university’s provost sent an email to the entire faculty accusing her of disrespecting Native Americans by using the word “friends” and by not wearing gloves while handling the skull (148). In fact, as Weiss explains, gloves are not required and rarely used while handling ancient bones. But administrators now had their excuse. Not only did they bar Weiss from the lab—literally changing the locks—but they promulgated a new set of rules for handling specimens—rules, which, for the first time ever, forbade photography and required gloves. More: They prohibited “menstruating personnel” from handling bones in order to accommodate Native American religious taboos (167).

Stymied in her research, Weiss sued the university, demanding that she at least be allowed to view the X-rays she had taken of the bones. But even here, administrators chose to do the bidding of tribal activists. They claimed that NAGPRA (or more precisely, CalNAGPRA) required them to surrender the X-rays to a nearby tribe for destruction. Nothing in the law requires this, given that X-rays are not ancient artifacts, but as Weiss notes, universities often destroy priceless objects—or take even more irrational steps—for what they wrongly claim are legal reasons. One Berkeley museum, for instance, “repatriated to the Graton Rancheria Tribe a 16th century Spanish breastplate, Ming dynasty ceramics, and a bottle of Hires root beer” (183). Another museum surrendered to a tribe 184 wooden masks, which had been carved in the 1930s by Seneca tribal craftsmen for a public exhibition; it said the masks were “sacred” objects and therefore . . . inappropriate for public exhibition.

Weiss never did get the X-rays. She eventually settled her lawsuit, quit the university, and moved to New York, where she continued writing about the danger to science posed by NAGPRA—or more precisely, by the broader postmodernist ideology underlying that law. “Our ability to understand the past is being erased and replaced with a false narrative,” she writes—a narrative according to which “there’s just the oppressor and the oppressed; nothing factual; and who tells the narrative is more important than its validity” (206–7). Universities are locking away priceless collections, out of the reach of scientific analysis, and destroying specimens that could reveal the secrets of the past and the future. They do so to appease ideologues who characterize science as “oppressive” and who demand that religions—specifically, non-Western religions—be empowered to overrule evidence and reason. In fact, CalNAGPRA includes a “deference” rule under which judges in cases involving ancient specimens must treat Native religious beliefs as more reliable than scientific evidence.

Postmodernism and its legal consequences, such as NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA, are transforming schools and museums into temples where superstitious balderdash is presented as reliable knowledge. Weiss gives the example of New York’s prestigious American Museum of Natural History, which now requires curators to speak to inanimate objects, to ask their “permission” to do research, and to hang branches of Devil’s Club (a kind of plant) in doorways to prevent spirits from escaping from Native artifacts. One museum display case even contains a warning that people who are feeling “physically or emotionally vulnerable” should stay away, lest they be affected by the spirits within (205).

Weiss is right that such irrationality is a corrosive that will destroy science entirely if left unchecked, and she has an admirable grasp of the philosophical foundations of the crusade against science. “Postmodernism,” she writes, “has led to an environment where reason is eschewed for the embracement of victim narratives.” In blowing the whistle on such nonsense, she’s doing us a great service (215). Unfortunately, On the Warpath is frequently digressive and so studded with distracting swipes at “wokeness”—and with exclamation points in virtually every other sentence—that it may turn off some readers who might otherwise have been convinced. Gripes about “misty-eyed eulogies to Saint George Floyd,” for example, or speculation about the “subclinical psychopathy” of leftists on Twitter are more likely to dissuade than to persuade (132, 95).

Still, after surviving what must have been a grueling betrayal by an institution she once revered, the remarkable thing is how little bitterness Weiss conveys. Instead, she ends on a positive note—heading toward new discoveries with a resolution to fight for reason and knowing that she does have allies—including the most important ally of all: the truth.