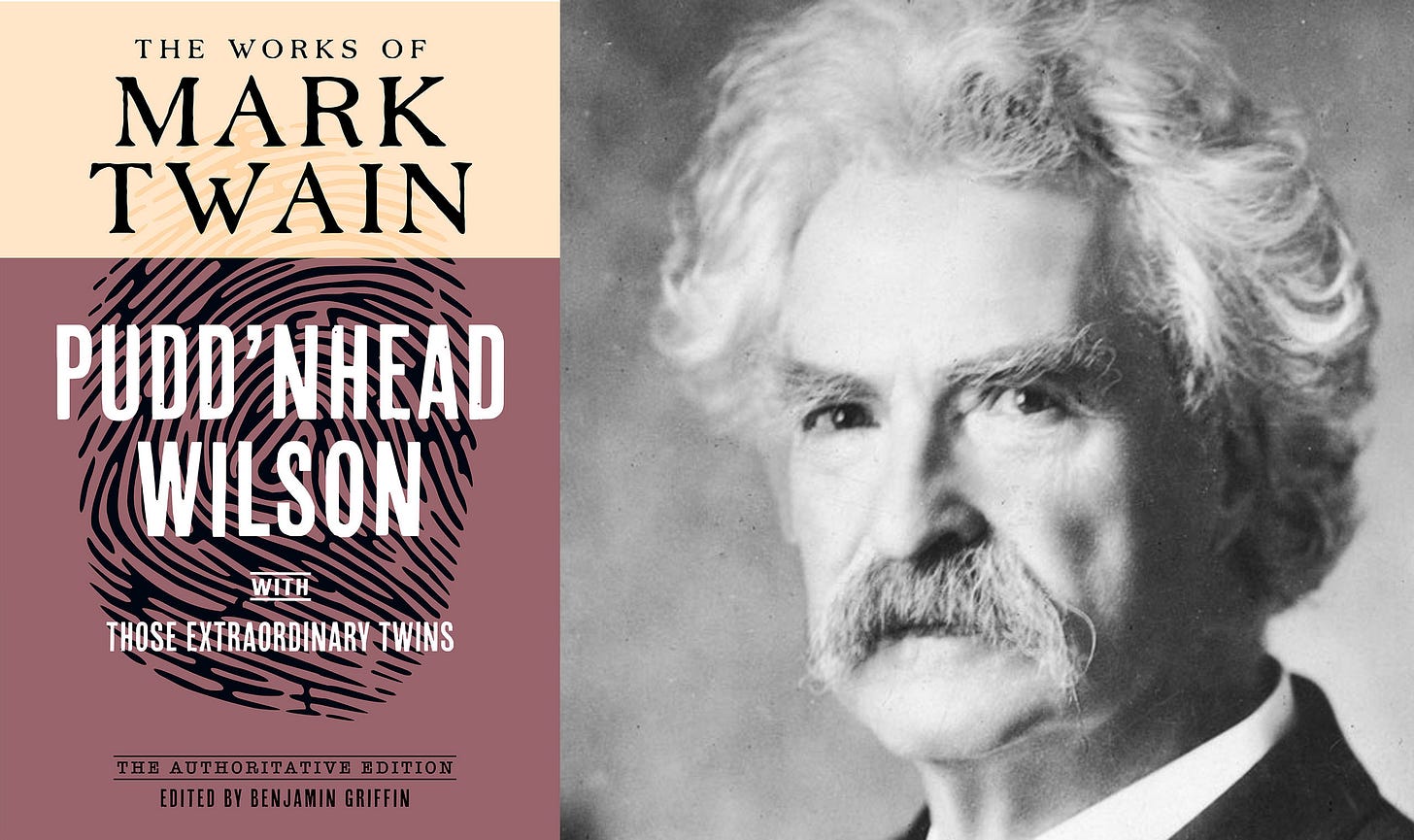

Pudd’nhead Wilson with Those Extraordinary Twins: The Authoritative Edition by Mark Twain, edited by Benjamin Griffin

By Timothy Sandefur

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2024

835 pp. $19.95 (paperback)

Pudd’nhead Wilson is an odd book by any measure. Originally published in 1894, it contains much of Mark Twain’s celebrated irony and cleverness, as well as his most earnest and brilliant denunciation of racism—far more powerful in that respect than anything in Adventures of Hucklebe…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Objective Standard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.