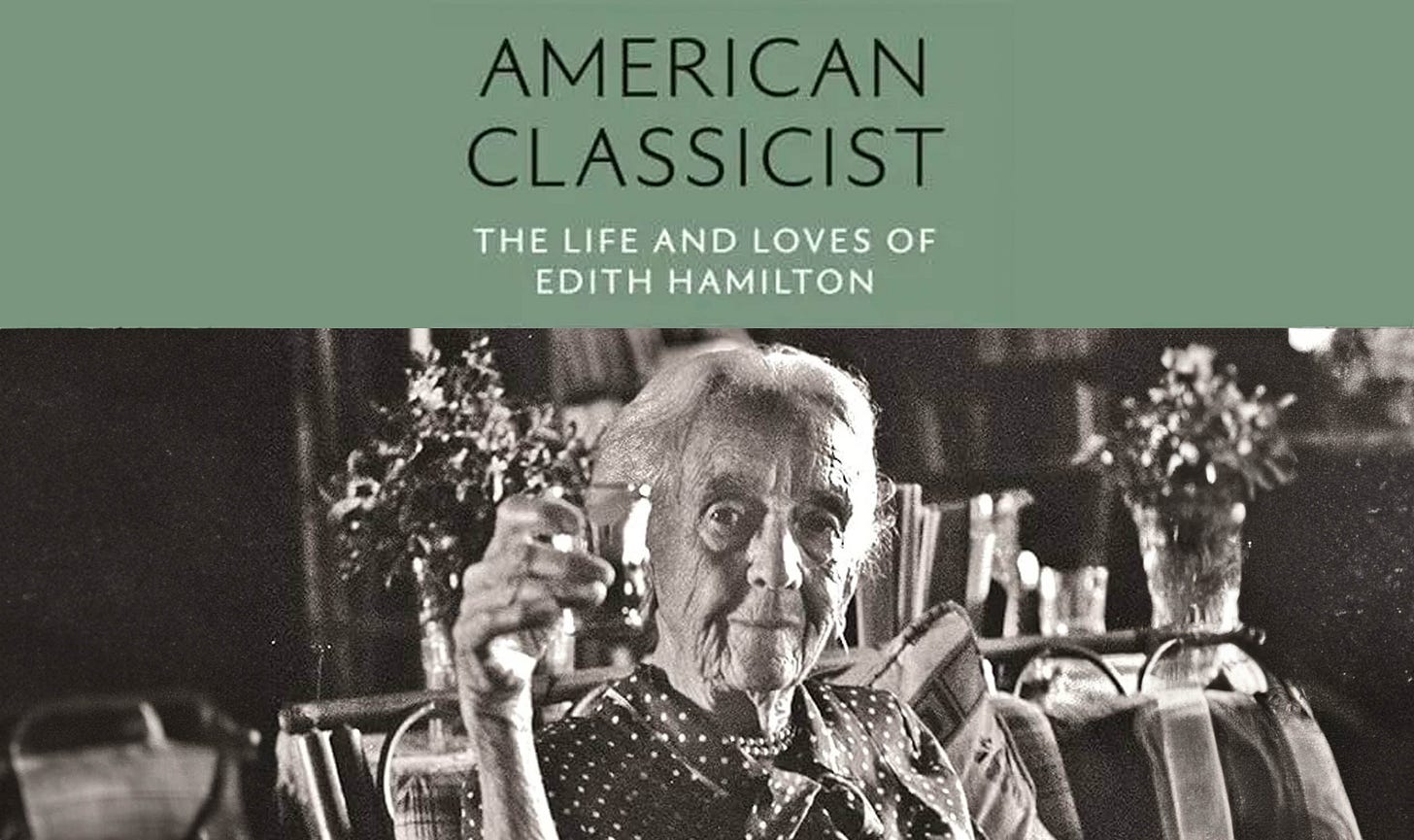

American Classicist: The Life and Loves of Edith Hamilton by Victoria Houseman (Review)

By Timothy Sandefur

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023

489 pp., $39.95

It’s been almost a century since Edith Hamilton published her classic The Greek Way, and during those years, countless thousands of readers have encountered Greek culture for the first time through her works—which include Mythology, The Echo of Greece, and translations of Plato, Euripides, an…