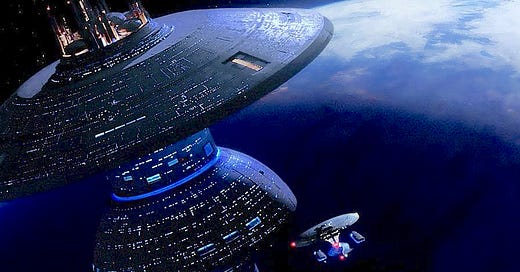

Star Trek Inspires People ‘to Boldly Go’

Star Trek has inspired people to “to boldly go” and become scientists, adventurers, and innovators.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Objective Standard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.