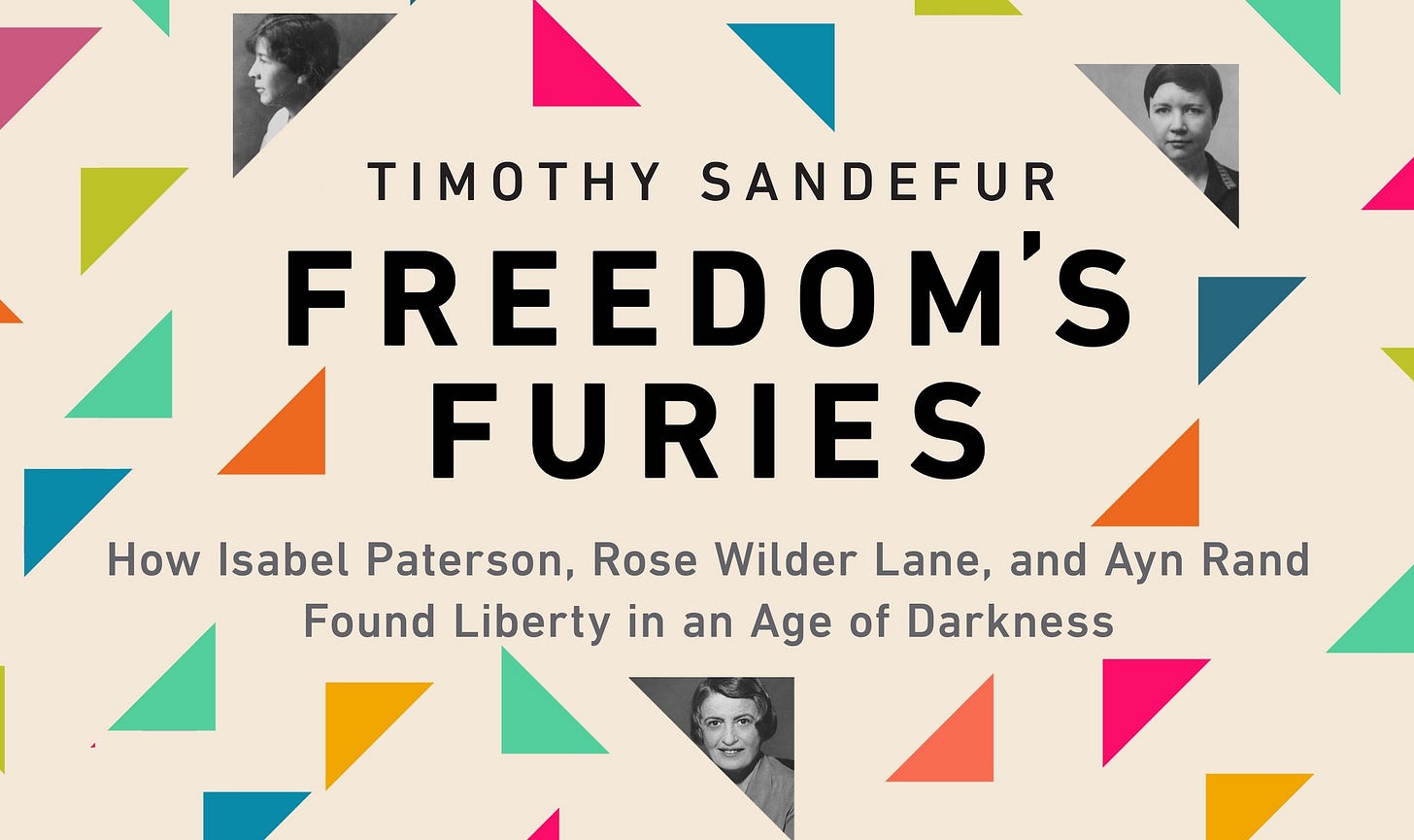

Freedom’s Furies: Timothy Sandefur on the Importance of Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane, and Ayn Rand

By Jon Hersey

During WWII, while American forces battled dictatorial regimes overseas, three writers back home were unleashing a full-scale assault on the ideas at the very base of tyranny. Isabel Paterson’s The God of the Machine, Rose Wilder Lane’s The Discovery of Freedom, and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, all published in 1943, launched the modern American liberty…