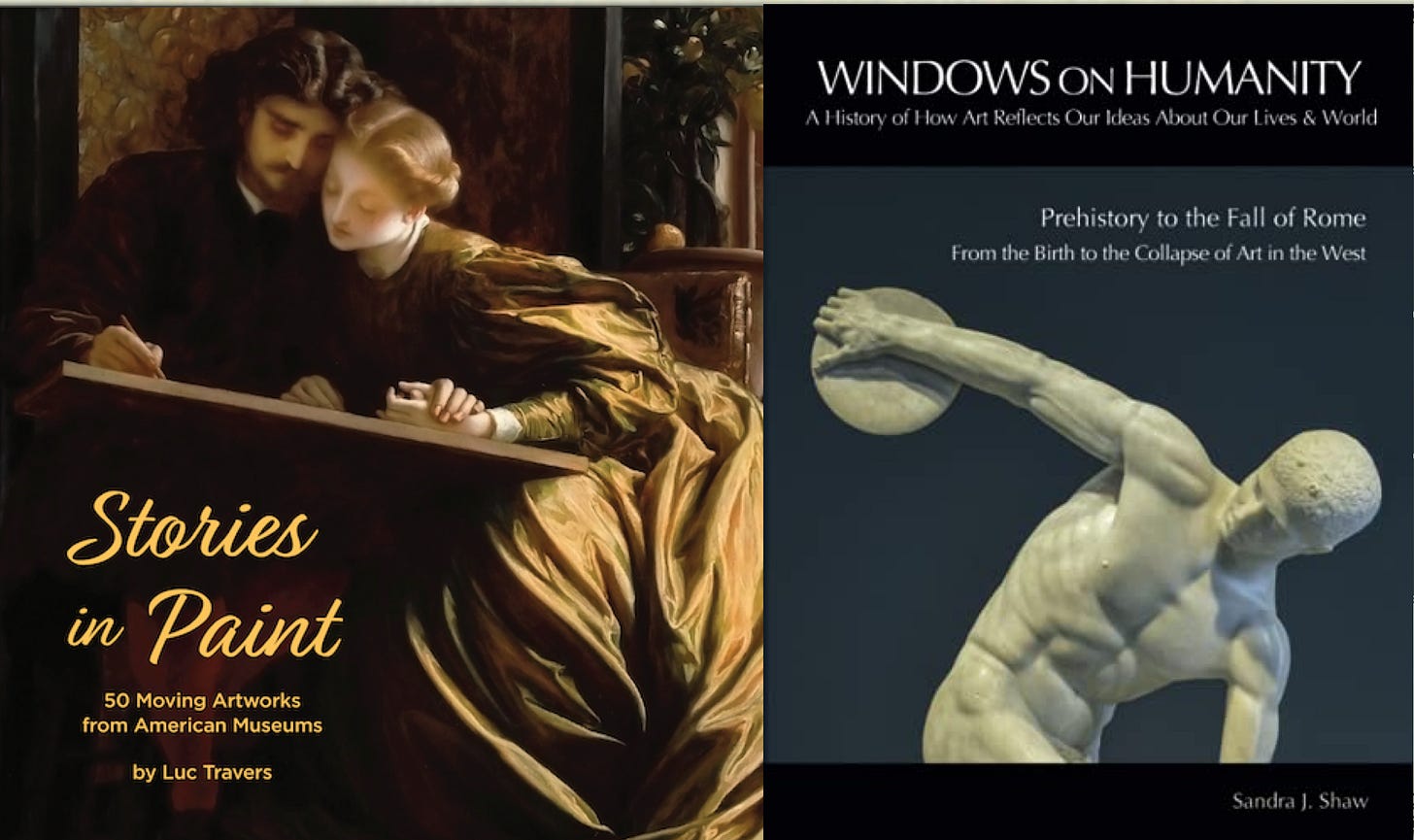

Stories in Paint by Luc Travers and Windows on Humanity: A History of How Art Reflects Our Ideas about Our Lives and World by Sandra Shaw (Review)

By Timothy Sandefur

Stories in Paint by Luc Travers (Self-published, 2021), $75, 119 pp.

Windows on Humanity: A History of How Art Reflects Our Ideas about Our Lives and World by Sandra Shaw (Self-Published, 2021), $47.97, 489 pp.

Ray Bradbury once remarked that, sometime in the 1960s, all the art sneaked off the canvases and jumped onto the movie screens. That, he said, exp…