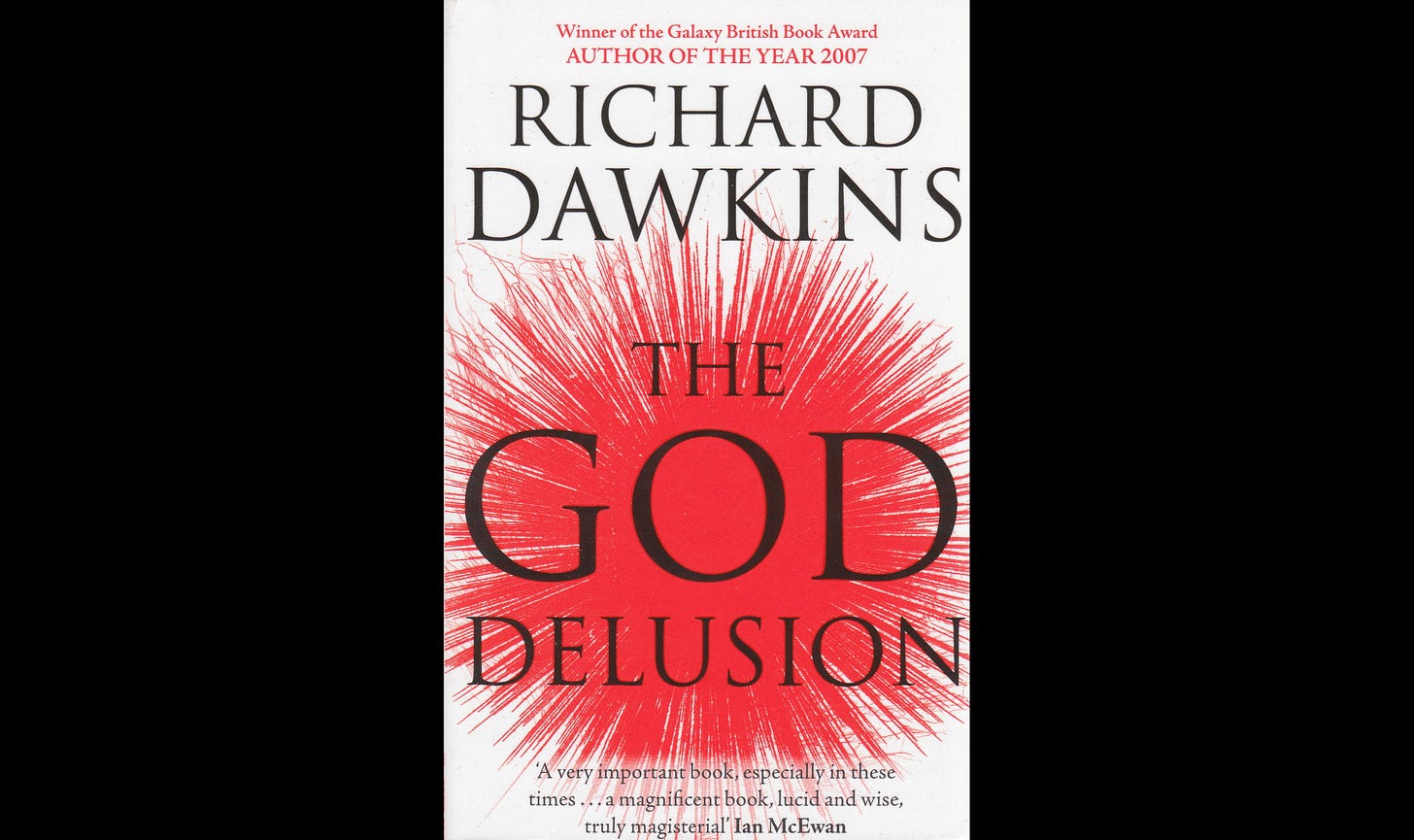

London: Black Swan, 2007

420 pp., $9.99 (paperback).

The God Delusion is a provocative title; billions of people the world over believe in the existence of a god or gods. But Richard Dawkins insists that his book’s title isn’t hyperbolic. The Penguin English Dictionary’s definition of delusion is: “a false belief or impression,” and he dedicates the first…