Working inspires inspiration. Keep working. If you succeed, keep working. If you fail, keep working. If you are interested, keep working. If you are bored, keep working. —Michael Crichton

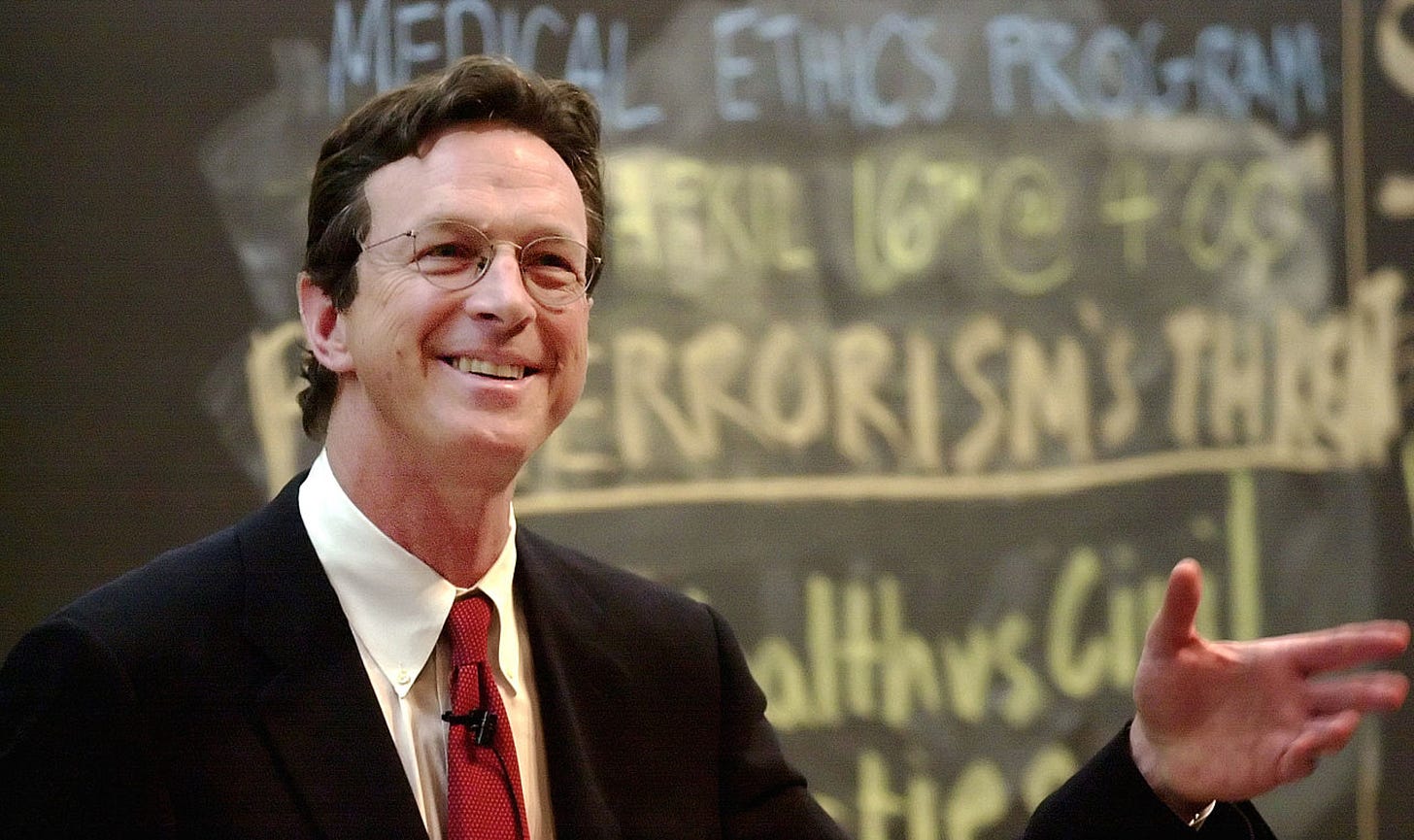

Imagine creating the nation’s number one book, number one movie, and number one television show all in the same year. Michael Crichton (1942–2008) achieved this twice: …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Objective Standard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.