Celebrating Progress and Combating Complacency: An Interview with Virginia Postrel

By Jon Hersey

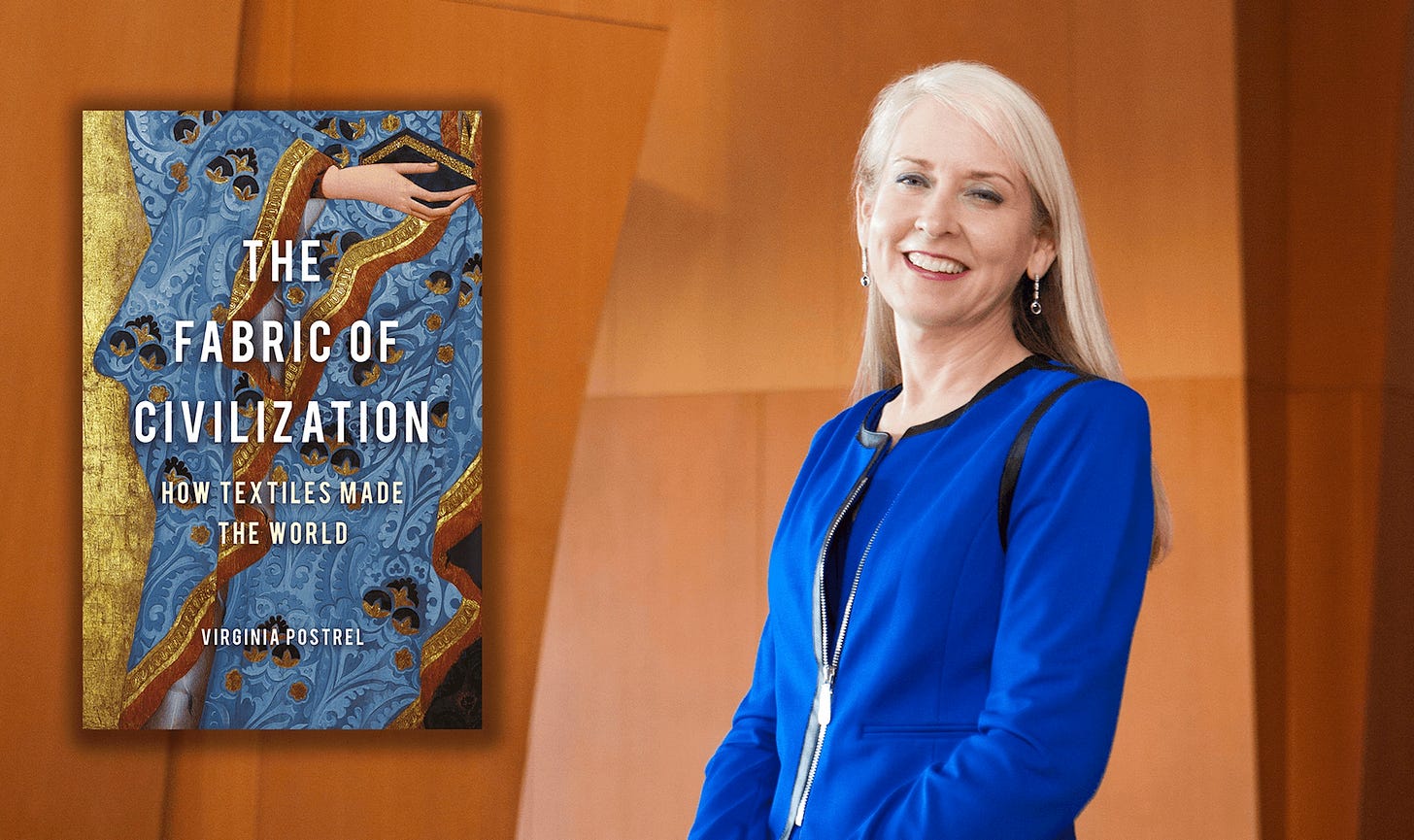

Few writers in the liberty movement are as dynamic and inspiring as Virginia Postrel, former editor of Reason magazine and author of The Future and Its Enemies (1998), The Substance of Style (2003), The Power of Glamour (2013), and The Fabric of Civilization (2020). Winner of the 2011 Bastiat prize, Postrel started her writing career reporting for the W…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Objective Standard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.