Screenwriting by Craig Mazin

Starring Jared Harris, Stellan Skarsgård, Emily Watson

Production Company: Home Box Office (HBO), Sister Pictures, Sky Television, The Mighty Mint, Word Games

Rated TV-MA

Running time 330 min

Author’s note: This review contains spoilers.

On the evening of May 2, 1986, my sister and I were doing homework in our room when my mother rushed in, telling us to pack our things. She took us to the train station and bribed a conductor to get us on a train to Moscow. We’d live in a stranger’s home near Moscow for the next four months. Our home in Kyiv was no longer safe because, one week prior and only sixty miles up the river, Chernobyl’s nuclear reactor No. 4 had malfunctioned, causing an explosion and releasing airborne radioactive contamination. Officials had announced that everything was under control, but in the days that followed people inferred the truth, which led to panic and to a frenzy of parents trying to get their children as far away from the area as possible.

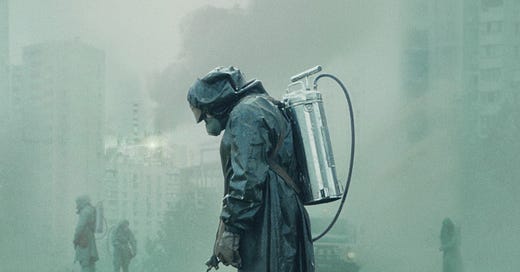

The events surrounding the worst nuclear disaster in history, which killed thousands and affected the lives of millions, are chronicled in the five-part docudrama Chernobyl.1 Although it was created in 2019, more than three decades after the disaster, it dramatizes with startling detail the events of the night of the accident and the unprecedented cleanup efforts that followed. Chernobyl explores the reasons for this monumental catastrophe and illustrates how it was magnified by the evasion and denial of those in charge.

Chernobyl immerses viewers in the events of April 26, 1986. At 01:23:45, a woman in the nearby town of Pripyat in the Soviet Ukraine witnesses an explosion followed by a column of blue light emanating from the direction of the nuclear power plant. Several neighbors gather their children and head to a railway bridge to better view the “beautiful” blue light. What the residents of Pripyat don’t yet know, and won’t for thirty-six precious hours, is that this column of blue light is air ionized by extreme radiation from an exposed nuclear reactor.

Seconds after the explosion, in the control room of reactor No. 4 at Chernobyl’s nuclear power plant, a dazed man utters, “What just happened?” That man is Anatoly Dyatlov, the plant’s deputy chief engineer, who is in charge of the control room that night.

Chernobyl demonstrates how Dyatlov’s unwillingness to face the facts resulted in numerous deaths and perhaps led to the explosion itself. As control room workers scramble to figure out what happened, Dyatlov concludes, without evidence, that the explosion was from a hydrogen tank—a serious problem but not a catastrophic one. When a plant worker runs into the control room shouting that “the reactor core exploded,” Dyatlov says, “He’s in shock. Get him out of here.” When the worker attempts to explain, Dyatlov tells him, “You’re confused,” and the man is dismissed.

Dyatlov continues to evade that the core had exploded even after seeing smoldering rubble that he knows (or at least ought to know) to be radioactive. He continues to send plant workers toward the open reactor, and he sends firefighters to fight a roof fire, which, unbeknownst to them, is blazing next to an exposed nuclear reactor and highly radioactive rubble. Viewers later witness these men suffer and die terribly of acute radiation poisoning.

We see how woefully unprepared the Soviets were for any type of accident or malfunction. In one instance, in the moments after the explosion, plant workers realize that the only dosimeter at hand is not capable of reading high radiation levels. Chernobyl, a nuclear power plant with four active reactors, has only one dosimeter capable of measuring high radiation levels, and it’s locked in a safe. When the key for that safe is finally found, the dosimeter burns out the second it’s turned on. Dyatlov decides to report to his superiors the maxed out number of the inferior dosimeter, disguising the gravity of the situation. We also see plant workers responding to the nuclear disaster without protective equipment.

Later, however, we see the local executive committee meet inside a nuclear bunker, where, in safety, they decide to close all the roads out of Pripyat to “prevent the spread of misinformation,” demonstrating their evaluation that the safety and reputation of Soviet officials are of much higher priority than the safety of the plant workers or the people of Pripyat. Like Dyatlov, and in part because of him, most of the officials informed of the accident are in denial of its seriousness.

A high-ranking state scientist, Valeriy Legasov, deduces the gravity of the situation from the disjointed evidence listed in a report and manages to break through the denial. He is called in to a meeting at the Kremlin to discuss the accident. He and Boris Shcherbina, the deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, are sent to Chernobyl to lead the months-long cleanup efforts, for which some six hundred thousand Soviet men were conscripted.

Although Legasov and Shcherbina are the right men to deal with the disaster, they do it at tremendous personal cost. “We’ll be dead within five years,” Legasov tells Shcherbina. Despite the danger, they soldier on, facing unprecedented obstacles that the state exacerbates. One of their biggest challenges is to clear the highly radioactive rubble from the roof of the exploded reactor building so that a “sarcophagus” can be built around it to contain the exposed nuclear fuel. The rubble is so radioactive that electronics won’t work without special protection, and it is fatal to humans within minutes of exposure. The Soviets ask West Germany to help by providing a robot but, embarrassed to admit the actual radiation level, specify one far lower. The robot breaks down almost as soon as it’s deployed. Shcherbina is enraged when he finds this out, and he and Legasov have no choice but to use “biorobots”—human soldiers—for this terrible task. To the Soviets, the state’s reputation is more important than human lives.

Interspersed with depictions of the cleanup efforts are stories of individual victims. We follow Lyudmilla, the young pregnant wife of Vasily Ignatenko, a firefighter on the scene that night. Lyudmilla watches as her young husband slowly dissolves from radiation poisoning before being buried in a mass grave inside a welded metal box, with concrete—not earth—poured over it. For his efforts, Vasily is not even granted the dignity of an individual grave or funeral.

We follow young Pavel, one of the six hundred thousand men conscripted as part of the cleanup efforts. Pavel, who looks to be barely out of high school, is plucked from his life and ordered by the state to go to Chernobyl. He dons an “egg basket”—a scavenged sheet of lead to cover his private parts in an attempt to protect himself from radiation—and is tasked with “liquidating” pets, presumably because they’re radioactive. The cost to Pavel’s psyche—and, likely, his body—is incalculable.

Meanwhile, a scientist named Ulana Khomuyk (a character representing the dozens of scientists who assisted Legasov) steadfastly searches for the truth. Encouraged by Legasov, she tries to learn why, before this, no reactor core had ever exploded—and what caused this one to explode. She uncovers redacted documents and a fatal design flaw, and for her efforts, the KGB arrests her.

During the trial of Dyatlov and Chernobyl’s director and chief engineer, we learn how a failed safety test and a string of lies and coverups led to the biggest nuclear catastrophe in human history. In his testimony, Legasov points out that the defendants are indeed responsible, but that they are not the only ones. Who else is? Here, in front of the world, Legasov must make the nearly impossible choice: lie and be complicit in another Chernobyl-type disaster, or tell the truth and suffer the consequences of exposing the corruption of the Soviet system. He is moved to utter, “Every lie we tell incurs a debt to the truth. Sooner or later that debt is paid.”

The miniseries, created and written by Craig Mazin and directed by Johan Renck, is tense and gritty. The ubiquitous portraits of Lenin and Soviet slogans such as, “Our goal is the happiness of all mankind!,” help set the place and time. The production details are accurate down to the helmets the miners wore, as Mazin discusses in a special six-episode podcast. In this podcast, he also discusses his interest in the story, production decisions, and how some of the real events are different from those dramatized. Mazin’s writing makes for drama that stays close to fact, and the cast does an excellent job depicting the horrors of the events. Although Mazin could have done more to underscore that the disaster was the result of Soviet statism, that message nonetheless is clear enough for thoughtful viewers to catch.

Mazin and Renck deserve credit for clearly and compellingly telling a complicated story about the often confusing events surrounding the Chernobyl disaster. Given how traumatic this event was for me and my family, it took me a long time after the miniseries was released to muster the courage to watch it. Although the true toll of the disaster on millions of lives will never be known, Chernobyl goes a long way toward helping us understand the real causes and effects of this catastrophe, and it’s well worth the five hours.