Tal Tsfany on Sophie, the Book

Exploring Objectivism Through the Eyes of a Heroic Young Girl

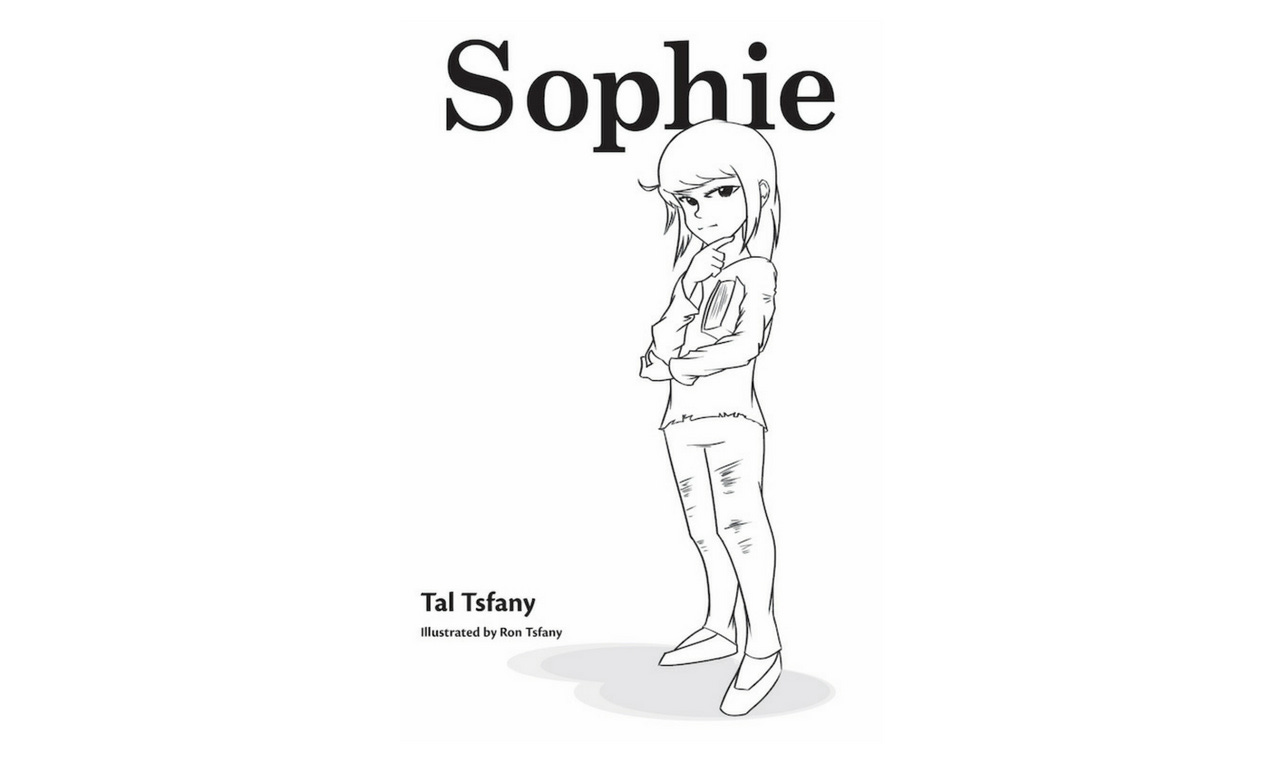

I recently had the pleasure of speaking with Tal Tsfany about his new book, Sophie. Tal is an entrepreneur, investor, businessman, and cofounder of the Ayn Rand Center Israel. He recently accepted the position of president and CEO of the Ayn Rand Institute, beginning at the end of June. This interview, however, is solely about his book, Sophie. Although…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Objective Standard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.