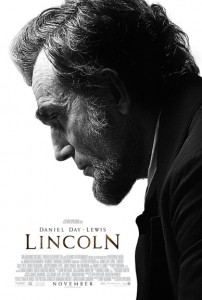

Lincoln, directed by Steven Spielberg. Written by Tony Kushner. Based on the book Team of Rivals by Doris Kearns Goodwin. Starring Daniel Day-Lewis, Sally Field, David Strathairn, and Tommy Lee Jones. Rated PG-13 for an intense scene of war violence, some images of carnage, and brief strong language. Running time: 150 minutes.

Lincoln is not what I expected. It is not primarily the dramatization of the life of a man, Abraham Lincoln, the nation’s sixteenth president. It is instead the dramatization of the passage of a law, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the first section of which states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” However, as the film makes clear, it is largely the force of Lincoln’s character that gave those words the force of law, so the film is aptly titled.

Few films deal fundamentally with the passage of a law. One of the few is Amazing Grace, the 2006 film about William Wilberforce, who in 1807 led the political movement to abolish the slave trade in the British Empire. Lincoln is a worthy successor, dealing with the American continuation of the same fight to abolish slavery. . . .