Author’s note: This essay is based on a lecture delivered at the Objectivist Conference (OCON) held in Newport Beach, CA, July 2008, and retains some of the informal character of an oral presentation.

While people commonly disagree about competing world views and substantive ideologies—arguing the merits of different religious creeds or value systems, for instance, of environmentalism or dominant business practices, of volunteerism or the specifics of political platforms—many are blind to the fact that nearly all these ideologies are fueled by a single, more basic philosophy: pragmatism. As people increasingly complain that political candidates are “all the same,” in fact, many of the ideas and approaches supported by these candidates do reflect a shared method. It is important to understand this common element not simply because of the breadth of its influence, but because of its destructiveness. While pragmatism presents itself as a tool of reason and enjoys the image of mature moderation, of common sense and practical “realism,” in truth, it is anything but realistic or practical. Pragmatism has become a highly corrosive force in people’s thinking. And insofar as it is thinking that drives actions—the actions of individuals and correlatively, the course of history—as long as a person or a nation is infected by a warped philosophical approach, genuine progress will be impossible.

In this essay, I seek to demonstrate the stealth but all too live menace that pragmatism poses. Pragmatism is not a substantive set of doctrines so much as a way of thinking, a unifying approach that helps to sustain an array of doctrines that are, in their content, irrational. Because it is a method, however, and informs the way that a practitioner tackles any issue, it proves much more difficult to unroot than an erroneous conclusion. Moreover, thanks to its positive image, pragmatism tends to give harmful ideas a good name, bestowing them with the misplaced aura of reason. It thereby makes people who wish to be rational all the more susceptible to those ideas.

I will begin by clarifying exactly what pragmatism is and proceed to supply evidence of its prevalence. I will then consider the distinctive appeal of pragmatism, as well as the heart of its error—where its goes wrong. Next, I will explain its destructive impact, the principal means by which pragmatism is, indeed, corrosive. Finally, I will offer some thoughts concerning means of combating its influence.1

What Pragmatism Is

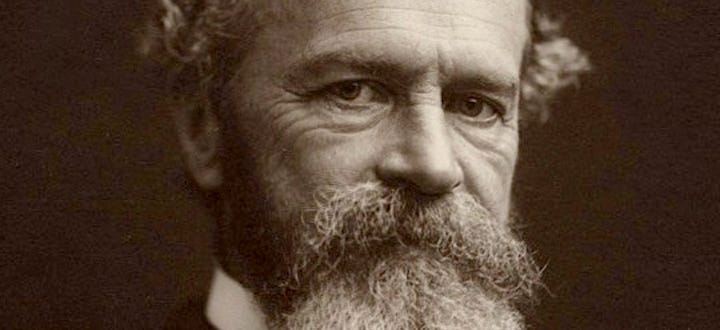

As a formal school of philosophy, pragmatism was founded by C. S. Peirce (1839–1914) in the late 19th century. Its more renowned early advocates included William James (1842–1910) and John Dewey (1859–1952). Primarily, pragmatism is a way of tackling philosophical questions. This, according to its founders, is what made pragmatism different from all previous philosophy. James wrote that pragmatism does not stand for any results or specific substantive doctrines; rather, it is distinguished by its method of “clarifying ideas” in practical terms by tracing the practical consequences of accepting one idea or another.2 The meaning and the truth of any claim depend entirely on its practical effects. The mind, accordingly, should not be thought of as a mirror held up to the external world, but as a tool whose role is not to discover, but to do, to act.3

What, then, should we make of the concept of truth?—or the concept of reality? Don’t we need to respect those, in order to achieve practical consequences? Well, of course truth exists, says James, but truth is not a stagnant property. Rather, an idea becomes true—“truth happens to an idea.” Truth “lives on a credit system” in his view; what a truth has going for it is that people treat it in a certain way. The true is the “expedient,” “any idea upon which we can ride.” Any idea is true so long as it is “profitable.”4

All truths do have something in common, then, namely, “that they pay.”5 The question to ask of any proposed idea is: What is its “cash value in experiential terms?”6 The traditional notion of purely objective truth, however, is “nowhere to be found.”7 The world we live in is “malleable, waiting to receive its final touches at our hands.”8 As Peirce memorably put it, “there is absolutely no difference between a hard thing and a soft thing so long as they are not brought to the test.”9 In the view of a much more recent and influential pragmatist, Richard Rorty, truth is “what your contemporaries let you get away with.”10 To call a statement true is essentially to give it a rhetorical pat on the back.11

In short, for the pragmatists, we find no ready-made reality. Instead, we create reality. Correlatively, there are no absolutes—no facts, no fixed laws of logic, no certainty.

While all of this conveys pragmatism’s basic character, a succinct definition is elusive. Indeed, James boasted of pragmatism’s protean inclusiveness, encompassing advocates of conflicting beliefs: materialists and idealists, theists and atheists, and so on.12 (In contemporary jargon, you might say that pragmatism is a “big tent” theory.) Moreover, when pressed, its distinctive method proves murky: We are to determine meaning and truth based on “practical consequences.” Which practical consequences? The consequences of believing a notion, or of its being so? How are we to measure consequences? What is the standard of practicality? Which ends should be advanced?

Leave aside such technical questions, however. The broad instruction of pragmatism quickly caught on; this was one philosophy that many were eager to put directly into practice (perhaps because it seems liberating to be told that reality is what you make it—your “final touches” can be powerful). And it is this broad sense of pragmatism that I shall be discussing in this essay. For our purposes, when I speak of pragmatism as a force in our culture, I am referring not to self-conscious disciples of James or Dewey, nor to pragmatism as a formal school of philosophy as precisely laid out by any particular figure, but to a looser cluster of mental tendencies that reflect its central thrust. I use “pragmatism” to refer to a style of thinking marked by four key features.

A short-range perspective. Perhaps most conspicuously, pragmatism involves range-of-the-moment thinking. This is clearly encouraged by the thesis that the yardstick of meaning and of truth is what works, and that since reality has no definite, enduring nature, what works today may be quite different from what works tomorrow. The here and now is paramount.

The inability (or refusal) to think in principle. Pragmatism rejects principles and erodes its practitioners’ ability to grasp principles, let alone to apply and be governed by them.

The denial of definite identity. The pragmatist characteristically resists identifying things by their essential nature. Whatever the subject of inquiry, each thing is regarded as sort of this and sort of that. Since reality is continually “in the making,” on pragmatist premises, so is each particular in so-called reality. To name things—to clearly identify or define an entity, an event, a policy, or any phenomenon—would be unrealistically constraining.

The refusal to rule out possibilities. Finally, when it comes to decision-making, the pragmatist’s inclination is to keep all options open—indefinitely. Whether he is negotiating differences with others or making a solitary, primarily self-regarding decision, nothing is ever off the table. After all, there is nothing that might not be “expedient” some day.

In essence, then, pragmatism is the absence of essence. It is the deliberate eschewal of identity and principle. Pragmatism champions the primacy of the piecemeal.

Pragmatism’s Prevalence

Given this portrait of what pragmatism is, we can now consider the various areas in which we encounter it. Even a little reflection quickly reveals that contemporary American culture is saturated with pragmatism. It is worth observing a variety of its manifestations in order to appreciate how deeply it penetrates our mindset and, correspondingly, how difficult it can be to dislodge.

Pragmatism is ubiquitous in the realm of politics and has been conspicuous in the 2008 presidential campaign, in which we have witnessed the familiar charade of candidates cultivating one profile during the primaries, only to polka to the center for the general election. These days, all viable candidates seek the “moderate” image—for, conventional wisdom has it, that is the way to be elected.13 Pragmatism was evident in the Democratic National Committee’s decision to seat the delegates chosen in the Florida and Michigan primaries at the national convention, but to recognize only half a vote for each. It brushed aside the party’s pre-announced rules for the 2008 primary season (which those states had violated) on the pragmatic rationale: But we mustn’t be rigid or rule-bound; we have to accommodate the Clinton backers.

In international affairs, we are routinely informed that it is only the extremist Islamists who pose problems. Any agenda that is not deemed extreme is greeted with open arms. Moderation is the test of respectability. Accordingly, engagement with one’s enemy is the mantra; one must always keep “dialogue” open, a peace “process” alive. Should one be so impertinent as to inquire into the validity of different camps’ competing positions, the typical (and thoroughly pragmatist) response is: “Whose validity? There is no moral truth, so there are no rightful claims.”

Consider the 2008 Olympics, which raise the question: Should nations that respect individual rights boycott games held in China, a notorious and ruthless abuser of rights? Many world leaders have answered, “No, . . . but we’ll skip the opening ceremony. ”When asked his position on this a few months before the games, Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama said that he would take a wait-and-see approach, emphasizing that he would leave the threat of a boycott “firmly on the table.”14

Turning to the field of law: In classrooms, professional training is dominated by professors who embrace positivism, which essentially rejects the place of principle in law. In courtrooms, judicial reasoning proceeds via “balancing tests,” which typically leave the standards of proper “balance” unidentified and undefended. Sandra Day O’Connor was widely lauded on her retirement from the Supreme Court a few years ago for her moderation and adherence to “judicial minimalism,” a method of splitting every difference, deliberately avoiding “sweeping” decisions, carving out the narrowest grounds for a ruling while saying as little as possible about the principles that ground it.15

A paradigm of pragmatism arrives in the recent, ballyhooed book Nudge: Improving Decisions about Wealth, Health, and Happiness, coauthored by the highly respected law professor Cass Sunstein.16 Nudge advocates “libertarian paternalism.”17 Its thesis is that while we should not force people to do things that are good for them (such as eat healthily, exercise, or save for their retirement), public and private policy alike should push people in that direction by deliberately structuring certain choices that they face—the way their options are presented to them as well as the associated default mechanisms—so as to make self-beneficial decisions more likely. Adoption of such a well-intentioned policy could mean, for instance, that a worker is automatically enrolled in a savings plan when he starts a new job and must take specific, deliberate action in order to opt out. Or again, it could mean that those designing the layout of offerings in a cafeteria deliberately place the fruit and yogurt and healthier foods in the most convenient, easy-to-grab locations, and the candy and less healthy alternatives in comparatively hard-to-reach shelves (far from the impulse-driven checkout counter, for instance). As an enthusiast writing in the New York Times describes the book’s central thrust: “It is a lot easier to trick people into doing what you want than to try to educate them or incentivize them.”18

Nudge’s authors concede that such “libertarian” measures are not a panacea. They cannot assure that individuals actually make good choices. Sometimes, therefore, a government will need to take stronger, more intrusive paternalistic measures. Yet often, Sunstein and Thaler contend, a “freedom-preserving” nudge will suffice.

(It should not be difficult to appreciate what such “libertarian” paternalism actually amounts to. Insofar as the book’s thesis addresses government policy, its proposal, in thoroughbred pragmatist fashion, fudges the identities of the policies under consideration and ignores the relevant principle, namely, the proper function of government. In fact, it is not the role of government to direct individuals to lead their lives in a particular way, be it allegedly self-beneficial or not. The government is charged with protecting individuals’ freedom, not manipulating people toward exercising their freedom in one way or another. What makes this book seductive, however, is the soft-edged pragmatism of its appeal, the unthreatening aura of a mere nudge. Its authors comfortingly assure readers that this is a defense of liberty, but one that is “practical.”)19

It is not only in law and politics that we encounter pragmatism; we find it also in education, sports, and across the cultural board. One of the most recent initiatives in schools to improve poor performance is to pay students for good grades.20 In the 2007 NFL season, when it emerged that the New England Patriots had been breaking league rules by spying on the signals of opposing teams, many defended them by reasoning, “everyone does it—you have to, to succeed; that’s life in the big leagues.”

We see pragmatism at work in much of the recent chorus of criticism of CEOs’ pay: “Sure, it’s fine for you and me to try to win raises and bonuses, but the money those guys get? That’s just too much.” Pragmatism infects popular attitudes toward journalism, where people increasingly believe that fact, fiction, opinion, and spin all merge into one. “Yes, I know that (documentary maker) Michael Moore distorts facts,” you’ll hear people say, “but there must be something to it. It’s truthy.” When disputes are still discussed in terms of facts, they are increasingly posed as a contest between “my facts” and “your facts”—as if we face numerous alternative sets, or as if reality has multiple personalities and a person may choose which identity to assign to it on a given day.

It is impossible to escape the conclusion that pragmatism pervades our ethos. It is palpable in the way that people approach all sorts of issues—in the homily of “tolerance toward all,” for instance, preaching that a person must forgive every transgression, regardless of the wrong, that virtue resides in “getting past our differences” (whatever those differences might be). Pragmatism animates the recent bumper sticker that spells out the word “coexist” by stringing together a peace sign, the star of Israel, the symbols of Islam, yin and yang, and others representing a variety of conflicting moral and political ideologies.21 The message conveyed by uniting this assortment of antithetical beliefs? Differences do not matter. Which, more deeply, implies that convictions do not matter; ideas do not matter; facts do not matter. The pragmatist, having rejected the very notion of facts, naturally applauds.

Pragmatism infiltrates our vocabulary. To wit, a “polarizing” figure is ipso facto a bad guy; “conciliatory” is the trait in demand. “Extremist” is a dirty word; “ideologues” are considered one step shy of the asylum. To speak of an “axis of evil” is lampooned as cartoonish. Note, too, that ours is an era of qualified names: “compassionate conservatism,” “democratic capitalism.” Internationally, we are urged by many to exert “soft power.” Labels are increasingly accompanied by qualifiers—in effect, ways of hedging our bets, taking it back, negating the very claim just made—because, as conscientious pragmatists, we all seek to be broad-minded “pluralists.” Expansive phrasing keeps one’s options open.

The ever-widening embrace of pragmatism is unapologetic. As the former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan, now widely revered as a modern day sage, matter-of-factly informs us, “compromise on public issues is the price of civilization.”22

All of these examples notwithstanding, it may be natural to suspect that my portrait is unfairly one-sided. Isn’t it the case that we still encounter forces in our society that are far from pragmatic? What about the radical environmentalists, for instance, or unabashed religious fundamentalists, who fiercely defend extreme principles? Isn’t the Bush administration widely decried as the most partisan ever? Don’t people still disagree righteously about certain issues, such as abortion? And, whatever you think of him, isn’t the success of Obama’s campaign a function of its hope and idealism?

Several points should be made, in response.

I readily concede that the evidence does not univocally point in the pragmatist direction. And many individuals, certainly, are torn between pragmatism and principle as they try to assess various issues. It is not uncommon for people to be pragmatists in some spheres and comparative “true believers” in others. My contention is not that there is not a principled person on the planet, but rather that such people are increasingly the exceptions and that the tide is decidedly pragmatist. In support of this, consider some of the specifics.

Without a doubt, politicians and others continue to make principled noises on occasion—for the simple reason that the rhetoric of principle still sells. Sounding such themes is thought to be practical. Nine times out of ten, however, words of principle are hollow. These days, when you hear a principle articulated, it is advisable to stay tuned, for a contradiction is almost invariably in the neighborhood, whether explicitly or implicitly. In May 2008, for instance, while on a visit to Israel, President Bush condemned talking with terrorists as appeasement, which sounded bracingly principled to many. Unfortunately, a quick scan of mental inventory reminded one that this is the same man who willingly engaged in negotiations with (and sometimes offered more positive forms of support for) a variety of parties he had previously condemned as evil.23 When words’ meanings are malleable, as pragmatism preaches, so are any purported principles expressed through such words.

Concerning abortion: The continuing debate over its proper legal status does not tell against the reign of pragmatism. Many Americans’ support for legal abortion is not support for a woman’s rights—the relevant principle—as evidenced by polls finding that many of those supporters approve of legal restrictions when they do not like the particular abortions that women choose to have (because a fetus tested positive for Down syndrome, for instance). A great number of Americans favor legal abortion primarily because it is convenient—always handy to have that option. Yet, their pragmatic attitude is, even convenience has limits and must yield at some point (“After all, it’s always a balance”).24

Similarly, what the “partisan” Bush White House is partisan about is not its dedication to any particular substantive principles. What it covets is power. Power to do what? Whatever—whatever will keep its preferred policy makers in office. Moreover, the haughty complaints about partisanship typically reflect the premise that political figures should not be principled or fight for ideas. Conciliation is always the right path.

While religion enjoys the image of commitment to principle, this image cannot withstand scrutiny. Religious people cannot be principled, in practice, because of the chasm between articles of faith and facts of reality. Irrational doctrines cannot be consistently practiced; those who profess such doctrines necessarily betray them in order to live. To the extent that any idea is accepted qua religious—because of its being decreed by certain authorities or thought to be issued by revelation—it is irrational.25 As such, it is inimical to the conditions of human existence (since the use of reason is man’s necessary means of survival).26 Those who profess to accept irrational doctrines (religious or otherwise) cannot avoid violating those doctrines on a regular basis. To characterize such people as principled is to distort language in precisely the manner fostered and required by pragmatism; it is to deny objective meaning by engaging in pragmatism’s anti-identity, “nothing is truly, definitively anything” premises.

(Interestingly, a major study of Americans’ religious views published by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life in February 2008 finds that an increasing number of Americans who are religious are unaffiliated. And most of these people described their religion as “nothing in particular.” In other words, people are increasingly uncomfortable with definitions; they do not like being locked in—to anything—including their allegedly principled ideals.)27

Finally, what about Obama-mania? Does the candidate’s appeal tap an idealism that belies my emphasis on widespread cultural pragmatism? Here again, even modest reflection proves otherwise. Note that Obama’s admirers acknowledge that for Obama, consensus “trumps ideological stridency.”28 A mentor describes Obama as “wanting to make the tent as large as possible.”29 According to the New York Times, dozens of interviews with political leaders and longtime associates in Chicago paint the candidate as “the ultimate pragmatist.”30 Within just weeks of Clinton’s capitulation after the primaries, Obama came under intense, prolonged criticism (from Republicans and Democrats alike) for flip-flopping on a range of issues (e.g., the funding of his campaign, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act [FISA], a troops pullout from Iraq, negotiations with Iran, offshore oil drilling).31

This Democrat’s campaign, alas, offers ersatz idealism. Notice what the “hope” is for: largely, a post-partisan America, where people’s differences (of race, income, gender, etc.) are overcome, and, most salient here, where we are all comfortable with ideological diversity.32 To urge the embrace of ideological diversity, however, is to endorse the pragmatist notion that the substance of an ideology—the content of one’s philosophical outlook, one’s views about what is real and what is important—is of little significance. Getting along is more important than where we are going. The substance of Obama’s policies, as was widely noted by commentators during the primary season, is not appreciably different from Clinton’s. Beneath the glamour, Obama simply offers new dressing for the tired, compromise-cobbled nanny state: government health insurance, help for some in an economic downturn, protection from jobs moving overseas. (This professed opponent of “politics as usual” could not bring himself to vote against the Farm Bill, its poster child.)

A deeper lesson can be drawn. What the portrait of Obama’s campaign as “idealistic” reveals is how the concept of idealism itself has been watered down by our culture of pragmatism. Like every other concept under pragmatism, idealism has come to mean . . . whatever. Obama-mania is not the idealism of rational principles—or even of principles. It is the pragmatic patchwork of what makes crowds of people feel good—“what works for me.” When one seeks to identify the content of the ideals that are supposedly gripping his supporters, all that one finds is emotionalism, amounting to the explanation: “I get goose bumps when I hear him speak.”

This tour of our culture’s rampant pragmatism is not uplifting. It is important to see how pervasive pragmatism is, however, in order to recognize its grip and to appreciate how easy it can be for a person to absorb a pragmatic outlook unwittingly. When so many signals around him reinforce the idea that this is what reason dictates, it is hard to resist. Indeed, who wants to resist being “rational” and “realistic”? In order to resist pragmatism, it is crucial to understand its appeal and its error. Let us turn to these.

Pragmatism’s Appeal and Fundamental Error

Why has pragmatism caught on? And what is wrong with it? Why should we reject it?

The appeal of pragmatism is hardly mysterious. It seems realistic—and every responsible adult knows that he cannot accomplish anything without being realistic. Part and parcel of this, pragmatism seems doable: This is a philosophy that can actually be practiced, that can guide people. It imposes no demands that we be saints or heroes; rather, it speaks to people as the (allegedly) imperfect beings we really are, not to the idealized characters of scripture or fiction.

Moreover, by being “realistic” in the ways that it advises, a person is seemingly forging progress toward his ends. Through pragmatism, a person seems free to serve that which is a man’s proper end, namely, his rational interest.

Further, and perhaps most seductively, pragmatism invariably presents itself in the robes of reason. The course it commends is branded as simply good sense (as in the case of the nudge). This, seemingly, reflects the grown-up view of what life takes. Pragmatism astutely exploits the fact that there is much to reject in most of the extreme ideologies on offer today. Given the unsustainable demands of collectivism or altruism, for example (doctrines that are nonetheless widely endorsed), pragmatism offers relief, a welcome loophole that releases people from the impracticable commands of these doctrines. Pragmatism authorizes deviations that do make sense, in other words, insofar as they are deviations from irrational ideals. It is no wonder that people flock to it.

The question is: Is pragmatism realistic? Is it rational? And does it serve anyone’s genuine self-interest?

The answer is no—three times. The reason is that pragmatism rests on erroneous conceptions of reality, of rationality, and of what it is to be practical.

First, when pragmatists urge compromise between any conflicting views, observe the nature of the “reality” that it would have us bow to. Which facts demand our respect? According to pragmatism, the answer is, fundamentally, other people’s beliefs—regardless of whether those beliefs make sense. That is, in the name of “reality,” pragmatists urge concessions to the _ir_rational ideas of others. There is nothing pragmatic about making a concession when a person who disagrees with you is right, when his ideas are rational. To the extent that pragmatism calls for unjustified concessions, however—for the propriety of concession as such—its deepest allegiance is to the beliefs of others. That is what constitutes the hard and fast “fact” that a person must respect: what other people think. In this way, pragmatism elevates man-made reality above metaphysical reality. Man’s beliefs about existents are considered more important and more real than those existents themselves. Indeed, in the pragmatists’ view, all reality is man-made. This is why, for the pragmatist, when “reality rules,” what that means is that consciousness rules. Other people’s beliefs and wishes about reality determine what should be respected as reality. The fact that some men may have correctly identified relevant facts on an issue and drawn logical implications, while others did not, is dismissed as insignificant. Metaphysical reality is not regarded as a check on man’s conclusions about reality, on the pragmatist view; it is not the basis on which we should evaluate a man’s assertions. Reality is malleable; correspondingly, we must be.33

The purportedly realistic character of pragmatism, then, is an illusion. And far from encouraging men to use reason, pragmatism’s instruction is diametrically opposed to reason. It is anti-conceptual. Its intellectual compass is restricted to what is immediately, perceptibly present. A man is to determine what is practical not by invoking relevant principles and not by integrating his awareness of one situation with his knowledge of others that are like it in significant respects, but by attending exclusively to what is here, before him, now. “I feel sure I can win this contract by lying, so honesty be damned.” “If I can get elected by making this interest group one promise and that interest group a conflicting promise (in artfully crafted language, of course), that’s my ticket.” Or, with William James, one might “deny the right of any pretended logic to veto my own faith.”34

This is not clear-eyed rationality, as the pragmatist contends. It is self-induced myopia. It is deliberate conceptual shrinkage.35 The pragmatic method militantly plants itself at the level of animals, instructing a man to attempt nothing higher than a beast’s type of mental functioning.36 And that is what it delivers; a subhuman level of existence is the prize toward which the pragmatists’ method is practical. The only “reality” that its method enables a man to know is a minuscule, transient, subjective slice: my perception, this instant. As Ayn Rand emphasized, however, human beings cannot survive by the methods adequate for lower animals. We cannot achieve the values that our existence requires without conceptual thought. Since reason is man’s means of survival, for pragmatism to turn its back on reason is for it to turn its back on life.

It should be clear, correspondingly, that pragmatism rests on an erroneous notion of what being practical consists of. On a rational understanding of the concept, an action or policy is practical when it is most likely to be effective in achieving an end—an end that should be achieved. This is not to say that people unfailingly use the term exclusively in this way, but that the truly practical course is one that both can be consistently practiced and that should be. Pragmatism, however, discards all objective grounds for evaluating what should be. Loosed from the constraints of reality, “proper” ends are whatever we like; it thus has no grounds for affirming anything as truly practical. What is practical by pragmatism’s lights is whatever a person thinks will work (rightly or wrongly) for whatever end he happens to seek (rightly or wrongly). (To put the point slightly differently, any action that will not advance a person’s objective, all-things-considered interest is not truly practical. By rejecting the absolutism of reality, however, pragmatism surrenders the grounds needed for the concept of objectivity and, correlatively, for objective evaluation of any conclusion, including claims about what is and is not practical.)

In the end, the most fundamental error in pragmatism is its opposition to reality. It denies the axiom of identity—the fact that A is A, that a thing is what it is. It denies the axiom of existence—the fact that “existence exists—and the act of grasping that statement implies two corollary axioms: that something exists which one perceives and that one exists possessing consciousness, consciousness being the faculty of perceiving that which exists.”37 It denies the law of excluded middle—the fact that it is impossible for the same thing to be F and not F at the same time and in the same respect.38 Pragmatism seeks to have things both ways—to have all things, all ways.

In fact, of course, reality is not shaped by the shifting tides of people’s beliefs. This is not the occasion to rehearse the inescapability of these axioms, the fact that one must presuppose them even in the course of denying them.39 Suffice it to say that a philosophy based on the denial of the most basic facts of reality could not hope to be practical or to serve a man’s genuine self-interest.

Pragmatism’s Destructive Impact

Once we understand the critical errors of pragmatism, we can readily appreciate the damage that it inflicts. Given its nature, and that it instructs a person’s way of thinking about all issues, its fundamental victim is reason—and consequently, knowledge and values. We cannot survey here all the derivative carnage that its irrationality rains on us, but it is important to register the major respects in which pragmatism poisons human life.

First, consider its effect on reason and knowledge. Pragmatism rejects principle as the tool needed for a human being to make his way in the world; it openly encourages un-principled action. Improvisation is commended not as an exception, occasionally needed in a pinch, but as the rule, standard operating procedure for handling life’s challenges. Pragmatism thereby disarms man’s true means of living, however, since reason is principled. The use of reason, at however basic or sophisticated a level, is an exercise in principled thinking—in identifying and integrating essential characteristics that unite a number of particulars. A culture cannot preach perceptual-level functioning and escape deterioration in its people’s ability to reason. This is distressingly apparent in the world around us. Numerous studies and commentators have documented the decline in people’s cognitive skills (e.g., their ability to identify or retain the essentials of major historical events, or their ability to solve basic math problems or understand rudimentary principles of science).40 In recent decades, America has been taking dumbing down to new heights. This is obvious in the level of public discourse about any issue; it is also increasingly evident in our habits, our judgment, and our attention span. Ours might be called a culture of distraction—we are all “ADD.”41 It is as if we have swallowed a pragmatism pill and become oblivious to all except that which is in front of us now, the immediately perceivable. The given item’s relationship to other facts or its larger significance are dismissed as impractical, theoretical questions. As a result of this trend, people are less and less equipped to judge what warrants attention and how to evaluate events. People frequently lament that rational standards seem to be on the decline in nearly every sphere, failing to notice that pragmatism is a major contributor to this. When ideas are a game—when ideas are not thought to be about reality because, according to pragmatism, there is no independent reality—people will not invest much effort in the rational scrutiny of ideas (or in cultivating the techniques of rational scrutiny). They will not seek out truths if they are convinced that truth does not exist.

Insofar as pragmatism attacks reason, it attacks everything that rests on reason. It destroys objective knowledge and objective standards. Accordingly, when government policy and a country’s culture are dominated by the methods of pragmatism, imagine the kind of schools we can expect. Or the kind of art, or science, or medicine. Or the kinds of laws and foreign policy. Sadly, we do not need to imagine these; we can see the sterile progeny of pragmatism on display all around us. (In the realm of foreign policy, President Bush offered a vivid exhibit when, on first meeting the Russian president Vladimir Putin a few years ago, he famously pronounced Russia a trustworthy ally because he felt good vibes. Bush recounted, “I looked the man in the eye. I found him to be very straightforward and trustworthy and we had a very good dialogue. I was able to get a sense of his soul.”)42

All of this is, admittedly, a rather unforgiving indictment of the dominant cultural trends of late, and one might wonder why such overt irrationality did not crop up earlier. After all, irrational philosophies have been around for ages. Destructive doctrines certainly predate Peirce and Dewey. The pragmatists, however, have served as pivotal, highly effective middlemen. They bottled the reality-denying doctrines of certain previous philosophers, principally Immanuel Kant, in a palatable formula that goes down much more smoothly.43

One might also wonder whether, despite the perils that I have pointed to, pragmatism nevertheless offers a certain saving grace. Because it condemns the advocacy of extreme positions, perhaps, to the extent that people accept pragmatism, it can slow the progress of today’s most noxious ideologies, such as rabid environmentalism. Perhaps the course of compromise that the pragmatist urges can buy time, in other words, against those who urge more substantively irrational agendas.

While it might be comforting to believe this, such a perspective amounts to wishful thinking. For pragmatism steadily convinces people that they do not need to take strong action in order to oppose destructive ideologies. It dampens the willingness to fight by spreading the belief that fights are never constructive; accommodation is all, splitting our differences is always the way to go. In a given case, admittedly, this might delay complete surrender to an erroneous school of thought. But pragmatism’s fundamental effect is to encourage unprincipled, irrational thinking. Slowing the tide by further entrenching the epistemology of pragmatism—its rejection of reality, truth, reason, and objectivity—is not the path to salvation. And this is what makes pragmatism especially destructive. As a philosophy that is essentially about epistemology, it strikes at the source of all of a person’s beliefs. It corrodes people’s manner of thinking about every issue, distorting the framework through which people view problems and conceive of possible solutions.

Pragmatism’s hostility to reason is explicit, and the effects of that assault are fairly plain. Less obvious is its correlative damage to values—both to existing values and to the very act of valuing.

Objective values are achieved only through reason. To the extent that pragmatism steers us away from reason, it impedes the creation of values. We cannot bring life-serving goods into existence by any means that defy reason. Makeshift tactics can occasionally bring temporary relief from the most pressing exigency (e.g., appeasing an enemy to stop him from attacking you today), but they thwart the deeper, conceptual thought that is required to sustain human life.44

Pragmatism does not merely impede the creation of values, however. It destroys existing values. This is evident today in the economy, where we are choking production through regulations that are invariably pragmatist in inspiration—designed to quiet this clamoring constituency or that, whichever needs placating more urgently. Pragmatist measures are responsible for our standard of living sliding backward in a number of areas—in air travel, where we are increasingly paying for peanuts, pillows, and luggage; in health care, where we are paying more money to obtain lesser quality.45

The pragmatists’ “quick fixes” fix nothing. On the contrary, they exacerbate existing problems, create more problems that will need fixing, and destroy previously achieved values.

It is crucial to appreciate this. The central prescription of pragmatism is compromise. Yet the consequences of pragmatism are inescapably toxic. As Ayn Rand pointed out, “In any compromise between food and poison, it is only death that can win. In any compromise between good and evil, it is only evil that can profit.”46 That which is true and rational and right has nothing to gain from that which is false and irrational and wrong. The latter can offer no value. Those who practice any irrational doctrine are, of necessity, parasites. Since the practice of irrationality does not work—since ignoring or denying relevant facts cannot result in the achievement of the values that human existence requires—people engaged in irrationality endure only thanks to the support they receive from the rational. When a person makes concessions to irrationality, he is cooperating in his own exploitation. He is providing the lifeline to those who (knowingly or not) suck his blood. While a given pragmatist may not look as obviously rotten as an overt preacher of a more blatantly noxious thesis, by appeasing evil through inappropriate compromises, he paves the way for the more deliberately evil to be effective.47

To put the point simply: The pragmatist who urges accommodation as standing policy is instructing a man to feed his enemy, to make concessions whose only effect will be to strengthen that enemy and to weaken the concession maker. He is urging a man to nourish his killer. The individual who loves his life must unequivocally decline the invitation.

To watch the erosion of one’s values is depressing. To be taught that this is proper—that all values should be surrendered on the altar of compromise—is demoralizing. Herein lies pragmatism’s damage not simply to values, but to valuing.

The thrust of pragmatism is egalitarian. When every position is to be accommodated, all ideas are leveled and all actions, however antithetical, are considered equally valid. One obvious result of this is injustice: The undeserving are rewarded, receiving better than they deserve, while the deserving are punished, receiving worse. But an even more insidious result is discouragement of the very act of judging. What is the point of evaluation, under pragmatism? If a person is told to not act on his judgments, but to give ground to others’ conflicting judgments, why should he judge anything at all? Pragmatism conveys the message that it is foolish for a man to seek values, since we have no basis for deeming some things as worthy ends. There are no true values (since there is no true anything). And, even if there were, it would not be appropriate for a man to pursue values seriously. Insofar as pragmatism counsels compromise, it counsels turning away from one’s goals, not going after them with conviction or commitment, avoiding such “extremes.”

Psychologically, I would speculate, the deeper effect of pragmatism is that it fosters an outlook of resignation, a disposition to settle for the “good enough,” an acceptance of the notion that muddling through is the best one can do. Pragmatism erodes aspirations and breeds cynicism—not bitter or hard-edged cynicism (since nothing has sharp edges, under pragmatism’s softening influence), but a hazy, overcast, unspoken hopelessness. It tamps down expectations. This may be its most tragic impact. To the extent that a culture is saturated in pragmatism, its sense of life is diminished. There is no fire in a culture—or a person—steeped in pragmatism. There is no ambition. And there can be little joy.48

Combating Pragmatism

Given the ubiquitous influence of pragmatism and its profoundly destructive effects, pragmatism needs to be vigorously opposed. To oppose it effectively, though, one must recognize the magnitude of the challenge and anticipate the obstacles that he will face.

Because pragmatism revolves around epistemology, it is an especially resilient adversary, for it is difficult to argue with a method of arguing—especially a method that denies the possibility of an objectively correct method. Normally, when a doctrine is mistaken, a rational argument can demonstrate that its conclusions do not follow from its premises or that its premises are false; one can point out faulty logic. Pragmatism, however, corrupts people’s understanding of what logic is.

Moreover (and, in part, as a result of this), many practitioners are not aware of their pragmatism; they do not recognize it as a distinctive view that they have adopted. A Marxist knows that he is a Marxist, just as a theist identifies belief in god as something that distinguishes him from certain other people. This is not true of the pragmatist. Many times, when a person disputes a pragmatist’s positions or method of approaching an issue, the pragmatist has trouble understanding what the objection is—how could anyone possibly disagree with his moderate, “reasonable” approach? Just as most people today assume that morality consists of sacrificing for others—that that is simply what being moral is—so most people assume that the solution to any problem is reached (in textbook pragmatist form) through bending and blending and reconciling differences. Such is the extent of pragmatism’s penetration. Awareness of these facts should restrain expectations concerning the pace at which progress can be made in loosening its grip, but such awareness should also impress on us the urgent need to actively challenge this creed. To that end, what follows is a handful of brief suggestions for combating pragmatism in others and, because even well-intentioned, essentially principled people can sometimes unwittingly fall prey to it, in oneself.

Perhaps the most basic step one can take to resist pragmatism is to place oneself on alert to spot pragmatism when it arises—and to name it when it does. One can institute a standing policy of identifying pragmatism and calling attention to its failures, pointing out how a particular pragmatic policy in health care, for instance, actually led to disastrous results, or how the Food and Drug Administration’s pragmatic compromises of competing interest groups’ demands do not successfully safeguard us. The point of raising such examples in discussion with others is neither to instigate arguments for their own sake nor to fulfill an anti-pragmatism duty. The aim, rather, is to better the world for one’s own sake by helping others to realize that pragmatism is not actually practical and that an alternative to the prevalent pragmatist assumptions does exist.

Second, one can battle pragmatism by vigilantly policing the meaning of words, seeking to safeguard the objective meaning of concepts. One can consciously resist being spun by convenient labels that others quickly attach to news events or cultural trends and that reinforce pragmatist presumptions. In this vein, it is crucially important not to yield to pragmatists the title of being “realistic” or “practical.” And it is even more imperative not to allow the word “reasonable” to be used as a fudge term that evades the Law of Identity, the fact that reality is absolute and that morality is black and white. “Reasonable” is frequently employed these days in a way that replaces the concept of the “rational” with the woolly “kinda rational” or “wanting to be rational.” When used in this way, however, what is allegedly reasonable is not rational. A proper understanding of rationality is indispensable to any viable defense of rationality.49

A third means of battling pragmatism lies in defending idealism. To show the impracticality of pragmatism, it is important to spotlight the practical value of its antithesis: devotion to ideals. Point to the success of people who are committed to principles and who live by rational ideals. Documenting the efficacy of idealism is a powerful means of disabusing people of the notion that compromise is the path to success.

The remaining suggestions more directly concern managing oneself.

It is important to beware the pull of the present. Because one is always in the present, immediate circumstances can naturally seem to be the most important consideration when confronting any decision. Pragmatism’s compromises typically appear as shortcuts that offer some relatively near-term satisfaction. Psychologically, that which is nearer tends to exert a disproportionate attraction for human beings that will prevail by default unless a person makes a deliberate effort to step back and use his conceptual capacity to understand his immediate situation in its larger context. In light of this, the person who wishes to resist pragmatism must exert a conscious effort to properly frame his perspective. He must adopt the policy of pulling back from his most immediate thoughts and feelings about a situation to think in principle about what he should do given all the relevant facts and the long-range requirements of life.

Similarly, a person needs to be on guard against the pull of the practical—on the commonplace, shallow notion of what that is. It is always wise to be practical, of course, but a person must make sure of which course furthers ends that are objective values and thus is truly practical, all things considered. (Notice that if a person does not fully understand the practicality of adherence to rational principles, he will be especially susceptible to pragmatism’s lure of pseudo-practicality. On a proper account of reason and morality, a person is not to abide by principle as an alternative to being practical; rather, allegiance to rational principle is a man’s means of being practical. Fidelity to principle may not always be the most convenient course, but following a valid principle is never not in one’s interest. Much of what is needed for a person to conquer pragmatism, in other words, is a matter of fully understanding the practicality of a rational code of action.)50

It is also crucial to acknowledge a different sort of challenge. Avoiding pragmatism requires accurately distinguishing legitimate compromise from illegitimate—that is, compromise regarding optional matters (e.g., the price you are willing to accept for your house) and compromise on moral matters (e.g., the principle of honesty regarding its condition). A person must judge when a concession would be fully rational, given the circumstances, and when a concession would amount to a pragmatic sellout. This judgment is sometimes (objectively) difficult to reach. No recipe can ensure a person’s getting it right. Two observations can be helpful when facing it, however.

First, a person must be completely honest with himself about the reasons that favor a given alternative. Whenever he has a doubt or nagging misgiving about one of the considerations he is weighing, he must probe what lies beneath it, in order to determine whether or not the reservation is valid. In doing this, he must listen particularly for internal rationalizations. Every pragmatic decision relies on some rationale; consequently, a person needs to carefully check whether the salient rationale is valid or merely a pretext.

Second (and truly, this is a further element of complete self-honesty), avoiding illegitimate compromise requires perseverance in the face of complexity. A person must not allow the complexity of a given case to deter him from making the effort to sort it out; he should not treat the difficulty of understanding a situation as an excuse to not try to resolve it by the relevant rational principles. He should not, for instance, quickly surrender to an internal voice assuring him, “oh, it isn’t such a big deal,” when part of him still believes that it is. Because it is naturally the complicated cases that will be difficult to untangle, one must plan to confront such cases by patiently evaluating the competing factors by reason.

Any serious effort to repel pragmatism will inevitably demand another kind of tenacity as well. Because pragmatism is so widely and deeply entrenched in our culture, those who recognize its corrosive nature may naturally struggle against outrage fatigue, from time to time, and have their appetite for action worn down by attrition. It may occasionally be tempting to throw in the towel. To sustain motivation, the best antidote may be simply to regularly remind oneself of the stakes. To surrender to pragmatism is to surrender to the rule of irrationality—with all that that brings and all, as we have indicated, that that destroys.

Finally, the Socratic injunction to know thyself can prove invaluable in warding off the temptations of pragmatism. To fortify oneself to think and act on principle, a person should seek to know himself ever more thoroughly. By identifying his tendencies, good and bad—his weaknesses (areas where he might tend to compartmentalize, for instance) as well as his strengths and those strategies that help him to make good decisions, he can become better attuned to the particular types of temptations to which he will be most vulnerable. He can correspondingly plan the most promising means of avoiding succumbing to them.

Conclusion

Pragmatism is a pervasive yet little remarked-upon cultural force. It is dangerous in large part because people do not recognize the corrosive nature of its far-reaching effects. To the extent that people are aware of pragmatism, most of them mistakenly praise it as rational and practical. It is anything but.

This essay has only scratched the surface of an intricate, multi-layered phenomenon. By opening our eyes to pragmatism’s essential character, its taken-for-granted prevalence in numerous domains, and its deeply destructive impact, however, I hope to have indicated why the seemingly innocuous methods of pragmatism pose a mortal threat to rational values.